ACC 557 – Homework 2 Chapters 4, 5, and 6 Due Week 4 and wo.docx

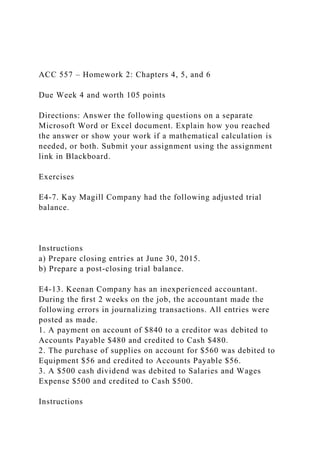

- 1. ACC 557 – Homework 2: Chapters 4, 5, and 6 Due Week 4 and worth 105 points Directions: Answer the following questions on a separate Microsoft Word or Excel document. Explain how you reached the answer or show your work if a mathematical calculation is needed, or both. Submit your assignment using the assignment link in Blackboard. Exercises E4-7. Kay Magill Company had the following adjusted trial balance. Instructions a) Prepare closing entries at June 30, 2015. b) Prepare a post-closing trial balance. E4-13. Keenan Company has an inexperienced accountant. During the first 2 weeks on the job, the accountant made the following errors in journalizing transactions. All entries were posted as made. 1. A payment on account of $840 to a creditor was debited to Accounts Payable $480 and credited to Cash $480. 2. The purchase of supplies on account for $560 was debited to Equipment $56 and credited to Accounts Payable $56. 3. A $500 cash dividend was debited to Salaries and Wages Expense $500 and credited to Cash $500. Instructions

- 2. Prepare the correcting entries. E5-4. On June 10, Tuzun Company purchased $8,000 of merchandise from Epps Company, FOB shipping point, terms 2/10, n/30. Tuzun pays the freight costs of $400 on June 11. Damaged goods totaling $300 are returned to Epps for credit on June 12. The fair value of these goods is $70. On June 19, Tuzun pays Epps Company in full, less the purchase discount. Both companies use a perpetual inventory system. Instructions a) Prepare separate entries for each transaction on the books of Tuzun Company. b) Prepare separate entries for each transaction for Epps Company. The merchandise purchased by Tuzun on June 10 had cost Epps $4,800. E5-7. Juan Morales Company had the following account balances at year-end: Cost of Goods Sold $60,000, Inventory $15,000, Operating Expenses $29,000, Sales Revenue $115,000, Sales Discounts $1,200, and Sales Returns and Allowances $1,700. A physical count of inventory determines that merchandise inventory on hand is $13,900. Instructions a) Prepare the adjusting entry necessary as a result of the physical count. b) Prepare closing entries. E6-1. Tri-State Bank and Trust is considering giving Josef Company a loan. Before doing so, management decides that further discussions with Josef’s accountant may be desirable. One area of particular concern is the inventory account, which has a year-end balance of $297,000. Discussions with the accountant reveal the following.

- 3. 1. Josef sold goods costing $38,000 to Sorci Company, FOB shipping point, on December 28. The goods are not expected to arrive at Sorci until January 12. The goods were not included in the physical inventory because they were not in the warehouse. 2. The physical count of the inventory did not include goods costing $95,000 that were shipped to Josef FOB destination on December 27 and were still in transit at year-end. 3. Josef received goods costing $22,000 on January 2. The goods were shipped FOB shipping point on December 26 by Solita Co. The goods were not included in the physical count. 4. Josef sold goods costing $35,000 to Natali Co., FOB destination, on December 30. The goods were received at Natali on January 8. They were not included in Josef’s physical inventory. 5. Josef received goods costing $44,000 on January 2 that were shipped FOB destination on December 29. The shipment was a rush order that was supposed to arrive December 31. This purchase was included in the ending inventory of $297,000. Instructions Determine the correct inventory amount on December 31. E6-6. Kaleta Company reports the following for the month of June. Instructions a) Compute the cost of the ending inventory and the cost of goods sold under (1) FIFO and (2) LIFO. b) Which costing method gives the higher ending inventory? Why? c) Which method results in the higher cost of goods sold? Why? Problems P4-3A. The completed financial statement columns of the worksheet for Fleming Company are shown on below.

- 4. Instructions a) Prepare an income statement, a retained earnings statement, and a classified balance sheet. b) Prepare the closing entries. c) Post the closing entries and underline and balance the accounts. (Use T-accounts.) Income Summary is account No. 350. d) Prepare a post-closing trial balance. P5-2A. Latona Hardware Store completed the following merchandising transactions in the month of May. At the beginning of May, the ledger of Latona showed Cash of $5,000 and Common Stock of $5,000. May 1 Purchased merchandise on account from Gray’s Wholesale Supply $4,200, terms 2/10, n/30. 2 Sold merchandise on account $2,100, terms 1/10, n/30. The cost of the merchandise sold was $1,300. 5 Received credit from Gray’s Wholesale Supply for merchandise returned $300. 9 Received collections in full, less discounts, from customers billed on sales of $2,100 on May 2. 10 Paid Gray’s Wholesale Supply in full, less discount. 11 Purchased supplies for cash $400. 12 Purchased merchandise for cash $1,400. 15 Received refund for poor quality merchandise from supplier on cash purchase $150. 17 Purchased merchandise from Amland Distributors $1,300, FOB shipping point, terms 2/10, n/30. 19 Paid freight on May 17 purchase $130. 24 Sold merchandise for cash $3,200. The merchandise sold had a cost of $2,000. 25 Purchased merchandise from Horvath, Inc. $620, FOB

- 5. destination, terms 2/10, n/30. 27 Paid Amland Distributors in full, less discount. 29 Made refunds to cash customers for defective merchandise $70. The returned merchandise had a fair value of $30. 31 Sold merchandise on account $1,000 terms n/30. The cost of the merchandise sold was $560. Latona Hardware’s chart of accounts includes the following: No. 101 Cash, No. 112 Accounts Receivable, No. 120 Inventory, No. 126 Supplies, No. 201 Accounts Payable, No. 311 Common Stock, No. 401 Sales Revenue, No. 412 Sales Returns and Allowances, No. 414 Sales Discounts, and No. 505 Cost of Goods Sold. Instructions a) Journalize the transactions using a perpetual inventory system. b) Enter the beginning cash and common stock balances and post the transactions. (Use J1 for the journal reference.) c) Prepare an income statement through gross profit for the month of May 2015. P6-3A. Ziad Company had a beginning inventory on January 1 of 150 units of Product 4-18-15 at a cost of $20 per unit. During the year, the following purchases were made. Mar. 15 400 units at $23 Sept. 4 350 units at $26 July 20 250 units at $24 Dec. 2 100 units at $29 1,000 units were sold. Ziad Company uses a periodic inventory system. Instructions a) Determine the cost of goods available for sale. b) Determine (1) the ending inventory, and (2) the cost of goods sold under each of the assumed cost flow methods (FIFO, LIFO,

- 6. and average-cost). Prove the accuracy of the cost of goods sold under the FIFO and LIFO methods. c) Which cost flow method results in (1) the highest inventory amount for the balance sheet, and (2) the highest cost of goods sold for the income statement? © 2015 Strayer University. All Rights Reserved. This document contains Strayer University Confidential and Proprietary information and may not be copied, further distributed, or otherwise disclosed in whole or in part, without the expressed written permission of Strayer University. ACC 557 Homework 2: Chapters 4, 5, and 6 (4-22-2015)Page 1 of 5 Donatello's Bronze "David" and "Judith" as Metaphors of Medici Rule in Florence Author(s): Sarah Blake McHam Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 83, No. 1 (Mar., 2001), pp. 32-47 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3177189 Accessed: 27/12/2009 20:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa.

- 7. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected] College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org http://www.jstor.org/stable/3177189?origin=JSTOR-pdf http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa Donatello's Bronze David and Judith as Metaphors of Medici Rule in Florence Sarah Blake McHam For all the individual analyses of Donatello's bronze David and Judith and Holofernes, these sculptures have rarely been considered jointly, despite the fact that they were displayed in coordinated outdoor spaces of the Medici Palace for about thirty years. I argue here that their iconography was meant to evoke republican themes, well known to the Florentine elite,

- 8. that the Medici aimed to embrace and co-opt.l The associated meanings of the David and the Judith and Holofernes were signaled by their related inscriptions. As I shall demonstrate by reference to Greek and Roman authors, particularly Pliny the Elder, these two works drew on descriptions of the Athenian statue group called the Tyrannicides, and on the writings of the twelfth-century English theologian John of Salisbury, all well known in fifteenth-century Florence, for the purpose of creating a visual rhetoric insinuating that the Medici were defenders of Florentine liberty. These literary and artistic sources combine with the two sculptures' related size and material to strengthen the likelihood that the David and the Judith and Holofernes were intended as pendants. Together the sculptures conveyed the controversial, self- serving message that the family's role in Florence was akin to that of venerable Old Testament tyrant slayers and saviors of their people, symbolically inverting the growing chorus of accusations that the Medici had become tyrants who had sucked all real power out of the city's republican institutions. The Statues' Setting Donatello's bronze sculptures of Judith and Holofernes (Fig. 1) and David (Fig. 2), according to evidence recently uncovered in contemporary sources, stood respectively in the Medici Palace garden and courtyard by 1469, possibly even as early as 1464-66.2 They remained in these adjoining locations until 1495, after the Medici were expelled from Florence in the previous year.3 We know that the palace was constructed for Cosimo de' Medici, between 1445 and the mid-1450s, but both sculptures are undocumented commissions.4 They were

- 9. installed in the palace within a decade after 1457, the approximate date when Cosimo, his two sons, and their families moved into the recently completed residence. The sculptures' status as two of the earliest freestanding Renais- sance statues makes the uncertainties of their dates and patronage particularly tantalizing, because these pieces are crucial to the reconstruction of the history of Italian Renais- sance art.5 Nevertheless, their existence in the Medici Palace courtyard and garden for about thirty years allows them to be studied jointly in the context of their placement within the most public spaces of the palace that served as the de facto seat of Florentine political power. Investigation of the sculp- tures reveals a prime and largely unexplored example of how Cosimo and Piero de' Medici contributed to the creation of a family imagery in the secular context most closely identified with it, the newly constructed palace on the Via Larga.6 The bronzes were focal points of the two connected open spaces, the courtyard and garden (Fig. 3). The axial arrange- ment of the palace's main entrance and courtyard means that the David, which was raised on a high base at the center of the courtyard, was visible even from the street when the main portal of the palace was open.7 Although there is no certainty about the precise position of the Judith and Holofernes in the garden,8 since the garden was just behind the courtyard, the sculpture could have been visible from the courtyard if it was situated on the garden-courtyard axis. Nevertheless, as the

- 10. courtyard was open to palace visitors and the garden to an invited group, the two statues were readily accessible to the desired audience.9 The family's suites were grouped around the palace's most striking innovation all'antica, the first colonnaded courtyard of the Renaissance, in which the David was positioned centrally. The courtyard, whose proportions and regular shape determined the impressive symmetry of the palace's plan, established a new type of interior formal space that came to supplant the exterior loggia on the Medici and other Florentine palaces as the site of formal receptions and family rituals. Behind it, the walled garden, with arcaded loggias at its north and south sides, provided a more private outdoor area, which was sometimes open to guests to the palace and used in conjunction with the central court when magnificent occasions, such as the wedding of Lorenzo de' Medici and Clarice Orsini in 1469, demanded additional space.'0 The Medici family expended considerable attention on the decorative program for the courtyard and garden. Comple- menting the classicizing columns in the courtyard were sgraffito decoration of garlands and shields decorated with the Medici palle (or balls), as well as a series of roundels above the arcade of the courtyard. These stone roundels, of uncer- tain date and attribution, seem like large-scale sculptures derived from ancient gems and incised precious stones acquired by the Medici. Perhaps they were intended to remind the visitor of the family's prestigious collection and interest in antiquity.11 There were ancient sculptures flanking the interior portals of the garden, notably, two of Marsyas on

- 11. either side of the exit to the Via de' Ginori.12 David as a Tyrant Slayer The recent discovery of the inscription once on the David ("The victor is whoever defends the fatherland. God crushes the wrath of an enormous foe. Behold! A boy overcame a great tyrant. Conquer, o citizens!")'3 seems to calm the con- troversy as to whether the sculpture indeed represents the young giant slayer, at least on a primary level.14 The inscrip- tion does not, however, narrow the range of dates for the sculpture, which different historians have placed as early as about 1428-30 and as late as after 1460.15 Most scholars agree, however, that the Judith and Holofernes probably dates after DONATELLO'S DAVID AND JUDITH: METAPHORS OF MEDICI RULE 33 1 Donatello,Judith and Holofernes, bronze. Florence, Palazzo Vecchio (photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York) Donatello's return to Florence from Padua, in 1453. Since the statue was recorded in the garden of the Medici Palace by 1469, possibly as early as 1464, it was most likely executed in the late 1450s or early 1460s and commissioned by Cosimo or Piero de' Medici.16 If the late dating of the David proves 2 Donatello, David, bronze. Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello (photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource)

- 12. 34 ART BULLETIN MARCH 2001 VOLUME LXXXIII NUMBER 1 3 Attributed to Michelozzo, Medici Palace courtyard, Florence, view toward garden (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) correct, then it could have been commissioned by the Medici together with the Judith, but at this point there is insufficient evidence to confirm the theory. The historical context of the bronze David provides some necessary background. Although very different in material and style from Donatello's earlier marble David (Fig. 4), it repeats the theme of David triumphantly standing with one foot on Goliath's decapitated head. Because David's identity as a victorious warrior has become so familiar to us through such later sculptures as Michelangelo's colossal David, we overlook that before Donatello's marble sculpture almost every representation of David interpreted him in other ways, as a king, prophet, writer of the Psalms, or ancestor of Christ.17 Documents indicate that in 1416 the marble David was transferred from the workshop at the cathedral of Florence and installed in the Palazzo della Signoria before a pattern of heraldic lilies painted expressly to complement it.18 Its site at the seat of government against a backdrop of symbolic lilies, the emblems of Florence's alliance with the Angevin dynasty, argues that the theme was interpreted in political terms.

- 13. Supporting evidence was recently found by Maria Monica Donato, who discovered two manuscript accounts that de- scribe the Palazzo della Signoria in the early fifteenth century. They allude to an inscription, "To those who bravely fight for the fatherland god will offer victory even against the most terrible foes."19 The manuscripts validate H. W. Janson's earlier, unproved speculation that this inscription might have been added to the sculpture by 1416, and that Donatello then recut the figure to emphasize a new political role for David as a defender of Florence by baring his left leg and removing the scroll formerly used to identify David as a prophet.20 The placement of the bronze David in the courtyard of the Medici Palace with an inscription of patriotic exhortation should be seen as a self-conscious allusion to the earlier marble analogue and its inscription. The marble David was at the time still standing in the priors' meeting hall in the Palazzo della Signoria, which made the Medici's identifica- tion with a symbol of the Florentine Republic all the more potent. The decision to situate an emblem of Florentine 4 Donatello, David, marble. Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) republican government in their palace could be understood as a sign that the Medici were closely connected to that regime and continued its ideals. Nevertheless, at the same time it represented an unprecedented appropriation by a single family of a corporate symbol of the state and informed the cognoscenti that true power resided several hundred meters north of the Palazzo della Signoria.

- 14. Judith as a Tyrant Slayer David and Judith are partners in meaning, which provides a rationale for their pairing. Both were Old Testament heroes and traditionally linked as saviors of the Jewish people in DONATELLO'S DAVID AND JUDITH: METAPHORS OF MEDICI RULE 35 Jewish and Christian imagery (as in an early medieval fresco at the church of S. Maria Antiqua, Rome, or on Lorenzo Ghiberti's East Doors for the Baptistery, where the statuette of Judith is placed in a niche next to the relief of David Killing Goliath).21 This partially explains their choice for the public spaces of the Medici Palace, but there were additional reasons for linking the two. Unlike David, Judith had not been politically associated with Florence, but the textual source, the apocryphal Old Testament Book of Judith, certainly lent itself to a political interpretation and was written to inspire Jewish patriotism.22 In the medieval period Jewish and Christian writers alike interpreted Judith as a moral, religious, and political heroine. In Christian symbolic thought her victory over Holofernes was elaborated as the triumph of virtue, specified variously as self-control, chastity, or humility, over the vices of licentious- ness and pride. In visual representations of Judith and Holofernes, which are usually found among manuscript illustrations of cycles of the virtues, she stands powerful over Holofernes, holding his sword in one hand and his head by

- 15. the hair in the other. Associations with these virtues meant thatJudith even came to be regarded as a type of the Virgin and of the Church.23 In the bronze by Donatello, the depiction of Judith and Holofernes continues these traditions. Judith's virtue is indi- cated by the demure clothing and veil that cover her from head to toe while Holofernes, in contrast, is almost naked.24 His nudity and drunkenness and the cushion on which he is propped identify Holofernes as a figure of Lust and Licentious- ness, whereas Judith represents Chastity.25 The medallion Holofernes wears, which has swung around to his slumping bare back, depicts a galloping horse, symbolic of Pride or Superbia, the vice traditionally defeated by Humility, repre- sented byJudith.26 Judith's valiant act of decapitating Holofernes is dramati- cally emphasized by Donatello, who created the first (and only) representation in monumental sculpture of this mo- ment. Equally unprecedented is Donatello's narration of the actual killing. Rather than interpreting the confrontation betweenJudith and Holofernes in the traditional emblematic language of Judith standing motionless over the fallen Ho-

- 16. lofernes, Donatello for the first time depicted the grisly detail of Judith's delivering a second blow to Holofernes, the one that results in his decapitation. The canopy she has ripped from Holofernes' bed (and later triumphantly presents in the Temple atJerusalem) is wound through his hair in her hand and around her upper back and thighs (Figs. 5, 6).27 The visual effect of these features encourages the spectator to circle the sculpture in order to appreciate gradually how the complex intertwining of the protagonists' bodies connotes their physical intimacy, and finally to confront the psychologi- cal nuances of Judith's expression of horrifying calm and steadfast resolve (Fig. 7). Judith raises Holofernes' scimitar high over her head and is poised to attack again. Vestiges on the weapon indicate that it was entirely gilded, and so this dramatic fulcrum of the sculpture must have shone in the garden sunlight at the statue's pinnacle, emphasizing the impending movement of Judith's arm.28 To ensure a deadly 5 Donatello,Judith, side view (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) cut, Judith steadies Holofernes' unconscious form by strad- dling his bare chest, bracing his head against her thigh, standing on his wrist, and grabbing his hair tightly. She has already opened a huge gash in his neck, and his head is collapsed unnaturally on his shoulders.

- 17. 36 ART BULLETIN MARCH 2001 VOLUME LXXXIII NUMBER 1 7 Donatello,Judith, detail: head ofJudith (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) ( i?! The inscription recorded on the base-"Kingdoms fall through luxury [sin], cities rise through virtues. Behold the neck of pride severed by the hand of humility"-underscores the moral meaning of the decapitation.29 The exhortation to the viewer to focus on the physical evidence of the truncated neck is unusual and important (this will be explored later). A second inscription connects its reference to contemporary _- ,. ~ z , ~-_ *Florence, "The salvation of the state. Piero de' Medici son of Cosimo dedicated this statue of a woman both to liberty and _:,- _ _or=f ..... ISto fortitude, whereby the citizens with unvanquished and constant heart might return to the republic."30 Together they echo the rallying cry for liberty against the evils of tyrannical rule carved on the base of the David. Relationship to the Athenian Tyrannicides The Judith and Holofernes and the David evoke references to tyrannicide well known to the Medici and to other members of the educated elite in Florence through ancient and contemporary texts. The fifteenth-century audience was famil- iar with accounts of two celebrated instances of tyrannicide in

- 18. "_lis;~*- , -the ancient world: the first, the attempted murder of Hippias in Athens, was hailed as establishing democracy in the west; the second, the assassination of Julius Caesar in Rome, was a ', > .~subject of continuing controversy. Considered a treacherous murder by some-for example, Dante31-others, like Boccac- cio, viewed Caesar's killing by Brutus and Cassius as a Donatello,Judith, back view (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) legitimate tyrannicide.32 6 .' - I " DONATELLO'S DAVID AND JUDITH: METAPHORS OF MEDICI RULE 37 8 Tyrannicide: Harmodios, Roman copy in marble of original Greek bronze. Naples, Museo Nazionale (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) The antityrannical inscriptions on the base of both sculp- tures by Donatello suggest a link to these renowned historical episodes and to the statue that became the most famous monument to tyrannicide in the West. The Tyrannicides (Figs. 8, 9), the monumental bronze group of Harmodios and

- 19. 9 Tyrannicide: Aristogeiton, Roman copy in marble of original Greek bronze. Naples, Museo Nazionale (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) Aristogeiton, heroically nude and advancing forward, ready to strike, was erected at public expense in the Agora to honor them for overthrowing the tyrannical regime that led to the establishment of democracy in Athens (despite the fact that they botched the attempt).33 The pair was given full honors as heroes, and their statue was considered such a symbol of the city and its liberty that the Athenians legislated that no other sculptures could be erected near it in the Agora. When the Persians conquered Athens in 480-79 B.C.E., they acknowl- edged the statue's symbolic importance to the city by carrying it off as a trophy. The Athenians immediately commissioned a replacement to stand in the Agora, and when the original Tyrannicides group was recaptured more than a century later and returned to Athens, it was placed alongside the second version of the theme in Athens's civic center.34 Only after Athens had been conquered by Rome was an exception made to the edict honoring the Athenian tyranni- cides by solitary prominence in the Agora: in 44 B.C.E. Athenian citizens voted to erect statues of Brutus and Cassius next to the Tyrannicides, thereby paying tribute to their slaying of Caesar in the same terms as the commemoration of Harmodios and Aristogeiton.35 General descriptions of the sculpture of Harmodios and Aristogeiton survived into the

- 20. Renaissance in writings by authors such as Pliny, Pausanias, and Philostratus. As one or more copies of each of these 38 ART BULLETIN MARCH 2001 VOLUME LXXXIII NUMBER 1 relevant ancient author's texts were housed in the S. Marco Library in the fifteenth century, the monument must have been known to the Medici family.36 Pliny's Natural History, in one of its most detailed accounts of any single Greek or Roman work of art, provided the fullest commentary. Pliny called the heroes and their sculpture symbols of Athenian democracy. He suggested that the Tyrannicides were among the first recorded examples of bronze sculpture, thus making them a landmark in the invention of that artistic form.37 He further recounted how the brave deeds of Harmodios and Aristogeiton were immor- talized by an inscription on the sculpture's base. Pliny specified that their portrait sculpture was installed at public expense in the Agora so that the feats of the tyrant slayers might live in the memory of Athenian citizens. He claimed the precedent started the fashion in many municipalities of decorating public squares with statues of heroes atop bases inscribed with their identities. He related the precedent to a subsequent practice of installing statuary in the private spaces of residences.38 Pliny embellished the story of the tyranni- cides with dramatic human interest by recounting the ancil-

- 21. lary episode of the harlot Laena, who was tortured to death rather than reveal the identities of Harmodios and Aristo- geiton, and of the monument of a tongueless lion erected in her honor by the grateful Athenian state.39 Ghiberti summa- rized Pliny's version of the story in his Commentarii, and Leon Battista Alberti's treatise on architecture repeated all major features of Pliny's description.40 In its own right, the epigram on the Athenian statue's base was just as celebrated as the sculptures. Attributed to the famous poet Simonides, it extolled the tyrannicides and their liberation of Athens with the words, "A marvelous great light shone upon Athens when Aristogeiton and Harmodios slew Hipparchus."41 Several drinking songs (scholia) derived from the inscription remained popular for centuries and were used to encourage patriotic emulation of the heroism of the tyran- nicides.42 The poetic inscriptions on the bases of the sculp- tures by Donatello, which distinguish the figures as exempla by invoking spectators' attention to their feats, may be inspired by that precedent.43 The statue group was widely copied in later Greek and Roman art; often, as in the case of the Brutus and Cassius statues mentioned above, imitations of the Tyrannicides were motivated by the goal of rallying patriotism in response to some threat to political freedom.44 There are a number of extant monumental variants, and renditions proliferated in copies and in versions on coins and vases and in relief sculpture. Characteristic aspects of the figures' gestures and poses were transferred to other heroes, such as Theseus, as a

- 22. sign of their identification with the political import of the Tyrannicides.45 The installation of the David and the Judith in the courtyard and garden of the Medici Palace recalls Pliny's allusion to the fashion of erecting sculptures in private residences that derived from the fame of the Tyrannicides. The sequence of these spaces in the palace suggests the atrium and peristyle of Roman houses, basic features of domestic architecture empha- sized by the Roman writer Vitruvius.46 In his treatise on architecture completed by 1452, Alberti elaborated on Vitru- vius's description and connected these spaces to the sort of public civic area where the Tyrannicides had been installed: ... the principal member of the whole building is that which I shall call the courtyard with its portico, to which all the other members must correspond, as being in a manner a public marketplace to the whole house.... (5.17)47 Places of public reception in houses ought to be like squares and other open spaces in cities ... in the center and most public place where all the other members may readily meet. (5.2)48 The incriptions of the Judith and Holofernes were later effaced and then recarved with pointed reference to the reinstated republic when it was transferred from the Medici Palace to the ringhiera, or rostrum once attached to the west side of the Palazzo della Signoria. This history suggests the intensity of the statue's political associations and may reflect awareness

- 23. of how the original Tyrannicides were carted off as spoils by the victorious Persians to be reinstalled as a symbol of triumph in the public space of their capital.49 The sculptures in the Medici Palace repeat features of the Athenian sculpture reflected in works of art and described in the literary sources. Like it, they represent tyrannicide through the medium of large-scale bronze sculpture of figures in dramatic action. The correspondences between the David, a bronze freestanding nude in the tradition of Greek heroic statues, situated in the courtyard of the Medici Palace, the analogous space in private residences to the public square of cities, reinforce the association. Judith's gestures of raising the sword over her head with one arm while thrusting forward her other, drapery-covered arm to grab the hair of her victim conflate the poses of the Athenians' arms as had the gestures of earlier heroes like Theseus and may reflect a limited knowledge of the Tyrannicides's actual physical appearance, pieced together from literary references and imitations of the group in the visual arts, or else fortuitously inspired by their laconic evidence into a partial resemblance. Historical Influence of John of Salisbury's Policraticus Another equally famous precedent regarding tyrannicide apparently influenced the fifteenth-century sculptures. Dona- tello's unprecedented emphasis on the physical acts of mur- der and decapitation seems to reflect the contemporary impact ofJohn of Salisbury's Policraticus. The Policraticus was a treatise about government written in the twelfth century by an

- 24. English theologian who became bishop of Chartres. It stood at the center of impassioned debate throughout Europe three hundred years later because it provided the most notable theoretical justification for the legitimacy of tyrannicide written by a Christian authority.50 The Policraticus had long enjoyed a special status as the earliest elaborate medieval exposition of political theory. Since it was based extensively on the Bible and patristic literature, the Policraticus was construed to represent the viewpoint of the Church. The treatise played a prominent role throughout the late Middle Ages and Renaissance in the popular genre of literature known as the "Mirror of Princes," that is, treatises written to instruct rulers.51John of Salisbury's theories about the nature DONATELLO'S DAVID AND JUDITH: METAPHORS OF MEDICI RULE 39 of the state directly engaged issues of political legitimacy and made the Policraticus influential on legal theory, philosophy, and political thought.52 For more than a century the treatise was considered the most authoritative work on government throughout Europe; it yielded its unchallenged supremacy to Thomas Aquinas, who drew extensively onJohn of Salisbury's theories and increased their circulation.53 After the mid- thirteenth century, the constitutional and political problems of legitimacy grew ever more urgent as new governmental units coalesced, and more attention focused on the Policrati- cus. Its influence was so significant in Italian legal and political circles that a fourteenth-century Bolognese jurist

- 25. wrote a reference index to its contents.54 The Policraticus became widely known as its many moraliz- ing stories proved a popular source for the teaching exempla cited by friars in their sermons. Finally, because the treatise drew extensively on ancient authors, interest in it was further stimulated by the incorporation of pagan classical literature into the curriculum of universities.55 In some circles the authority of the Policraticus was further enhanced by the misconception that the title represented the author's name and he was Greek.56 An excerpt, which John of Salisbury called the "Institutio Traiani" and claimed was written by Plutarch, was widely diffused independently. Regarded as a major ancient source on tyranny and tyrannicide, it was the only text attributed to Plutarch known and taught during the fourteenth and much of the fifteenth century.57 John of Salisbury's discussions of tyranny and tyrannicide had enduring popularity in Italy for additional reasons. He provided information and a theoretical context with which to assess the rulers of ancient Greece and Rome, making his work important to authors like Petrarch and Boccaccio. Petrarch's De remediis utriusque fortunae contains several dia- logues on the nature of tyranny.58 In the De casibus virorum illustrium, published in 1371, Boccaccio devoted several chap- ters to tyrants in the ancient world. But John's commentary had more specific implications in

- 26. Florence, one of the few Italian cities that remained a republic by the end of the fourteenth century, after most other Italian communes had evolved into semimonarchical or even tyrannical governments. Florentine claims for the city's foundation during the Roman Republic and other associa- tions to that venerable precedent were mainstays of civic pride and propaganda. This made the assassination of Caesar and arguments about whether tyrannicide was justified topics of particular significance. The Policraticus proposed the legitimacy of tyrannicide in a series of explicit arguments unparalleled in Western thought,59 with a key book of the treatise headed "That by the authority of the divine book it is lawful and glorious to kill public tyrants, so long as the murderer is not obligated to the tyrant by fealty...."60 When the Florentine chancellor Coluccio Salutati wrote a treatise called De tyranno in 1400, he naturally drew on the Policraticus. Salutati's text is the first by a major Italian political figure to focus on tyrannical government and the legitimacy of tyrannicide. His objective in writing it was to defend the reputation of Dante, who, rather than according immortality to Cassius and Brutus as tyrannicides, had deemed them murderers and relegated them to the lowest circles of the Inferno.61 Unlike John of Salisbury, who had considered Caesar a tyrant, Salutati argued that Caesar was a benevolent despot. Therefore, according to Salutati, Caesar's assassina- tion was not a legitimate tyrannicide, and Dante was right to put Cassius and Brutus in Hell.62 Not surprisingly, the numerous assassinations of contempo-

- 27. rary political leaders in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Europe and the tenuous hold on power of many more kept attention focused on the Policraticus's justifications of tyranni- cide. In 1407 the murder of Louis, duke of Orleans, brother of Charles VI, king of France, by John the Fearless, duke of Burgundy, thrustJohn of Salisbury's theories again into the spotlight. In a move that galvanized all of Europe, the duke of Burgundy denied that he had committed any crime, thereby skirting the obvious charge that the killing enhanced his own chance of succeeding to the throne of France. He contended that, as a loyal servant of the crown, he had been honor- bound to rid the country of a detestable tyrant who had perverted French royal institutions. His stance had grave theoretical consequences for rulers anywhere in Europe and direct ramifications not only for France and Burgundy but also for England and Italy. Henry V of England soon thereaf- ter married Catherine, the daughter of the French king, and the duke of Orleans left as his widow Valentina Visconti, the daughter of the duke of Milan. To argue his case, the duke of Burgundy hired Jean Petit, a distinguished theologian at the University of Paris, who argued on the duke's behalf that the murder of a tyrant was the praiseworthy obligation of a good Christian citizen. To buttress his stance that the Church sanctioned such assassina- tions, Petit drew on Thomas Aquinas and other theologians, but the defense rested onJohn of Salisbury's explicit theories

- 28. about the legitimacy of tyrannicide. Petit presented the position in a series of tracts entitled Justificatio Ducis Burgun- diae.63 The outraged son of the assassinated duke of Orl6ans demanded that their validity be judged by a Council of the Faith, attended by doctors and masters of the University of Paris. This distinguished group vehemently debated the issues throughout 1413 and 1414. The eminent theologian Jean Gerson represented the duke of Orl&ans's position that his father had been unjustly murdered.64 In 1414, the synod condemned the ideas of Jean Petit and required that all copies of the Justificatio be burned.65 Nevertheless, at the Burgundian court it was preserved as a precious document, recopied, and over the course of the century incorporated into the manuscript and ultimately the printed histories of Burgundy and of France.66 In response to the synod's decision, the duke of Burgundy brought his case before John XXIII, the claimant to the papacy not supported by the king of France. John first assigned a committee of Italian cardinals to make a ruling; he named them because of their experience, as Italians, with political assassinations.67 John XXIII subsequently decided that the matter should be put before the full-scale church council at Constance. There it was debated at great length, with Gerson again representing the position of the family of Louis of Orleans.68 Nevertheless, the Council of Constance broke up

- 29. in 1418 without ruling against the duke of Burgundy.69 Burgundian partisans immediately retook control of the 40 ART BULLETIN MARCH 2001 VOLUME LXXXIII NUMBER 1 royal government in Paris. Soon thereafter the University of Paris published a long letter excusing itself for the Council of the Faith's decision, on the basis that hardly any impressive masters of theology remained in Paris during its tenure. Royal letters were composed specifically disavowing the work of Gerson. The assassination of the duke of Burgundy in 1419 made his culpability a moot point but intensified the contro- versy about the succession of power in France and Burgundy, as well as the theoretical basis of legitimate government and citizens' rights to take action against unlawful rulers. Practical repercussions continued to be felt in Italy. Charles of Orleans, the son ofValentina Visconti and the assassinated duke, laid claim to various territories in northwestern Italy, including the duchy of Milan. Charles died in 1465, but the title of the house of Orleans to Milan did not. The French invasion of Italy at the end of the fifteenth century was mounted to enforce it. During the fifteenth century, other attempts to overthrow existing Italian governments sprang from native soil. The most significant occurred in Rome, Milan, and Florence; one plot achieved its goal of killing a head of state.70 In 1476 the Olgiati Conspiracy in Milan resulted in the murder of Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza.71Just a

- 30. couple of years later the Pazzi Conspiracy in Florence suc- ceeded in the assassination of Giovanni de' Medici, although his brother, Lorenzo, the head of state, escaped. Unlike their Milanese counterparts, the Pazzi conspirators did not justify their deeds by rhetorical allusions to legitimate tyrannicide, but other Florentines did so for them. In 1478-79, Alamanno Rinuccini wrote the treatise "De libertate," in which he likened the Pazzi conspirators to the heroic teams of Harmo- dios and Aristogeiton, Cassius and Brutus, and the Milanese conspirators.72 More than recurrent political crises, killings, and problems of succession kept alive the themes with which John of Salisbury had grappled. Riccardo Fubini has pointed out that the theological and political interpretation of a state's legiti- mate authority-the fundamental question left unresolved at Paris and Constance-festered in Florentine fifteenth- century political thought and led to successive crises such as the rebellion against Piero de' Medici in 1466 and the Pazzi Conspiracy. As he noted, the editorial debates leading to a new Latin edition of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics in 1463 demonstrate the continuing importance of the controversy.73 The Sculptures in Relation to the Policraticus Let us now return to the focus of this essay and examine how the two sculptures by Donatello relate to John of Salisbury's discussions of the state and tyrannicide. To begin with the obvious: they both depict tyrannicides. Judith's killing of Holofernes is made unprecedentedly dramatic. In addition to being the first monumental depiction of the episode, it is rendered as a freestanding sculpture whose physical tangibil-

- 31. ity heightens the explicit horror of the freeze-frame rendition of a murder in progress. That the tyrannicides are legitimate and morallyjustified is underscored by the inscriptions on the David and the Judith. The graphic aspect ofJudith's pause between two blows as she decapitates Holofernes and the inscription's focus on the severed head relate to the peculiarly precise anatomical characterization that is John of Salisbury's original contribu- tion to the long-standing analogy between the body and the state. He made clear that the prince is the state's head, and that it ineluctably followed that the tyrant, or prince who misruled, must be killed so that the head is severed from the body.74 Although he credited Plutarch's "Institutio Traiani" as his authority, John of Salisbury seems to have invented the details of the metaphor himself.75 John contended that tyrannicide was a duty if it set people free for the service of God.76 In support of his position, he cited various examples of the oppression of the Jews in the Old Testament and their deliverance by the slayers of these tyrants; by far the most important savior wasJudith, who killed the general of an army threatening her people.77 In the same chapter,John extolled David as a counter example. According to John's philosophy of fealty, David was bound by oath as a subject Saul, and so unlike Judith, who owed no allegiance to Holofernes, David could not rightfully murder Saul, even though he was a tyrant. John argued that David's patient,

- 32. passive resistance and decision to leave Saul's fate to God represented the moral course of action in such cases.78 Nevertheless, John realized that not all tyrants could be peaceably overcome and offered specific advice about depos- ing them by force. According toJohn, the most expedient way to destroy tyrants was to beseech God's retribution, but he explicitly sanctioned human dissimulation and treachery when they served the cause.79 In this regard, his most prominent case was again that of Judith, whose beauty and charms were enhanced by God,John tells us, so that she could entice Holofernes into a drunken stupor and kill him: Let me prove by another story that it is just for public tyrants to be killed and the people thus set free for the service of God. This story shows that even priests of God repute the killing of tyrants as a pious act, and if it appears to wear the semblance of treachery, they say it is conse- crated to the Lord by a holy mystery. Thus Holofernes fell a victim not to the valor of the enemy but to his own vices by means of a sword in the hands of a woman; and he who had been terrible to strong men was vanquished by luxury and drink, and slain by a woman. Nor would the woman have gained access to the tyrant had she not piously dissimu- lated her hostile intention for that is not treachery which serves the cause of the faith.... For this is shown by her words ... "Bring to pass, Lord," she prayed, "that by his own sword his pride may be cut off, and that he may be

- 33. caught in the net of his own eyes turned upon me.... Grant to me constancy of soul that I may despise him, and fortitude that I may destroy him. For it will be a glorious monument of Thy name when the hand of a woman strike him down." . . . she who had not come to wanton, used a borrowed wantonness as the instrument of her devotion and courage.80 Donatello's bronze representsJudith as chaste and humble, although the sensuous implications of her encounter with Holofernes and the ways in which she guilefully ensnared him are amply suggested by their intimate physical positioning: she stands on his wrist and straddles his chest.81 The topicality of John's treatise helps to explain the commission for the first monumental, three-dimensional DONATELLO'S DAVID AND JUDITH: METAPHORS OF MEDICI RULE 41 statue of the story of Judith and Holofernes. The brutal decapitation reflects his citation of Holofernes' murder as the prime example of justified killing of an overlord who dis- obeyed God's laws. John singled out the sword as the suitable agent of retribution against a ruler who unlawfully used it against his people: "For whosoever takes up the sword deserves to perish by the sword."82 The unprecedented portrayal of a decapitation in progress is the physical embodi-

- 34. ment ofJohn's theory about the actual separation of the head from the body politic, that is, the severing of the tyrant from his state in a whollyjustifiable murder.83 Even though David's killing of Goliath was not cited as an example of tyrannicide in the Policraticus, Donatello's depiction of the boy standing victorious, sword in hand, over the decapitated head of Goliath easily relates toJohn's ideas. Like Holofernes, Goliath was the major warrior of an army menacing the Jews. Holofernes' killing by a woman and Goliath's death at the hands of a boy could only have been accomplished with God's help. Despite the fact that David killed Goliath with a stone, the sword, the meansJohn recommended to slay a tyrant, and Goliath's severed head are emphasized. The inscription originally on the statue's base and the statue's inevitable association with the nearby Judith and Holofernes reinforced the appropriateness of interpreting the killing of Goliath as another illustration ofjustified tyrannicide. The David and the Judith and Holofernes, sculptural center- pieces of the two most public spaces in the Medici Palace, thus seem to have been coordinated in a program that was calculated to advertise to invited guests that Cosimo and his family were protectors of liberty-in a period when that was very much in question and in need of corroboration. Their control of Florence was sufficiently threatened that in 1458 Cosimo secretly consulted with Duke Francesco Sforza of Milan about sending troops to Florence should conspiring against the regime explode into fighting. Cosimo next master- minded a series of changes that weakened traditional republi- can governmental structures. These were confirmed by a sham parlamento, in which the intimidated citizenry sur-

- 35. rounded by armed soldiers voted to consolidate the family's hold on power. Cosimo and then Piero ruled for the next eight years, taking harsh measures to suppress any opposition. In this period they had a great need to deflect charges of tyranny from themselves. Donatello's statues conveyed that message powerfully by suggesting instead that the Medici family should be seen in the flattering light of celebrators, even preservers, of Florentine liberty against any threat, a self-serving political strategy that many Florentines would have considered outrageous.84 Related Aspects of the Courtyard's Decoration This reading of the statues is reinforced by their thematic and formal links to the other aspects of the decoration of the garden and the courtyard. Two ancient statues of Marsyas, restored in the fifteenth century, flanked the doors leading from the garden into the Via de' Ginori. One, now lost, represented a seated Marsyas prior to his torture.85 The other, depicting the torture of Marsyas, is presently in the Uffizi (Fig. 10). Recently Francesco Caglioti convincingly reattributed its restoration to Mino da Fiesole.86 He also argued that these two statues were included in the garden because the theme of 10 Marsyas, Roman sculpture with restorations attributed to Mino da Fiesole, marble. Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi (photo: Alinari) Marsyas could be understood as representing liberty. In support of that argument, he cited an unpublished commen-

- 36. tary by Giovanni Nesi on Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, which 42 ART BULLETIN MARCH 2001 VOLUME LXXXIII NUMBER 1 11 Attributed to Donatello, roundel of Centaur, stone. Medici 13 Attributed to Donatello, roundel of Triumph ofBacchus, Palace courtyard (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) stone. Medici Palace courtyard (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) 12 Attributed to Donatello, roundel of Daedalus and Icarus, stone. Medici Palace courtyard (photo: Alinari/Art Resource) Nesi directed to the young Piero de' Medici, the son of Lorenzo.87 The roundels of the courtyard's upper walls, which may have been designed by Donatello, further develop the mean- ing of the program.88 One depicts centaurs (Fig. 11), cited by Dante as incapable of successfully governing because of their supposed fault of pride.89 They therefore connect to the statues' allusions to prideful tyrants overcome by virtuous deliverers who restore liberty to their people. Another roun- del represents Daedalus and Icarus (Fig. 12). The proud Icarus is posed nude atop a high pedestal, recalling promi- nent features of the statue of David below. According to Francis Ames-Lewis, this similarity also establishes a link between the interpretation of the David and the roundel. He sees them together representing the results of contemplation of truth in a Neoplatonic sense, as the soul rises from the

- 37. terrestrial state to the divine state personified by Icarus.90 In this light, the statue and roundel together could be seen as validating the "truth" of the cycle. A third roundel, often considered to represent the Triumph of Eros, depicts a scene very close to that on Goliath's helmet, relating the roundel to the statue by Donatello (Fig. 13). Both the helmet decoration and the roundel have been identified in this way because of their compositional connections with a sardonyx cameo traceable in the fifteenth century to the collections of Pietro Barbo, and now in Naples.91 However, art historians had not taken into account that the gem was also identified as a Triumph of Bacchus, an interpretation applied by Patricia Ann Leach to the roundel and helmet decoration both.92 She argued that in this context the triumph suggested not only a Christian meaning of salvation but also a political sense of liberty, because of Boccaccio's description of how Bacchus or Liber brought liberty (libertas) to mankind.93 Wendy Stedman Sheard extended this line of interpretation by noting that Bacchus can be considered a god of military triumph and as such personifies the connection of peace and prosperity with the reign of a legitimate ruler, in this case the Medici.94 Artistic Patronage Converted to Political Power The interpretation of the statues and courtyard decoration accords with the claims of humanists seeking Cosimo's favor, such as the Sienese Francesco Patrizi. In his "Ad Cosimum Medicem virum excellentissimum," written about 1434, Pa-

- 38. DONATELLO'S DAVID AND JUDITH: METAPHORS OF MEDICI RULE 43 trizi flattered Cosimo as a new Brutus for his symbolic slaying of the tyrant Rinaldo degli Albizzi, or Caesar: Like Brutus, he, fearing for the Roman flower of Freedom, struck, and broke the tyrant's power.95 Not many humanists adopted this rhetoric. But it served the Medici well to create an imagery that advertised the family's stance as defenders of Florence. The prominent precedent of Donatello's marble David in the Palazzo della Signoria en- sured that the bronze David would have been immediately associated with the cause of Florentine liberty and the defeat of enemies of the state. By erecting Donatello's bronze David in the public space of their palace's courtyard and inscribing its base with an antityrannical message, the Medici were usurping this symbol of the republic and inverting its mean- ing-making themselves, not the republic, tyrant slayers like David. AlthoughJudith was a new symbol to Florence,John of Salisbury's citation of her as a paradigmatic tyrannicide made the Old Testament heroine a second exemplar. The bronze sculpture's unprecedented stress on Judith's encounter with Holofernes as a dramatic narrative of murder and decapita- tion derives from John's famous metaphor of the tyrannical prince as the head of the body politic who must be sundered from it by decapitation. The multiple connections among the Donatello sculptures, John of Salisbury's Policraticus, and the famed ancient statues of the Tyrannicides reveal another way in which Cosimo and

- 39. Piero created their family imagery, knowledgeably converting to their own aggrandizement venerable historical precedents in addressing a simmering contemporary controversy. By so doing, the Medici manipulated republican imagery to estab- lish the family's political propaganda, here subverting the charge of tyranny often leveled against them to their own purpose.96 The message was subtle and coexisted with more obvious and conventional interpretations of David andJudith as Old Testament heroes honored by Christian tradition. Scholars have demonstrated many examples of how the Medici employed a strategy of commissioning works of art that veiled their political thrust in a context of acceptable religious and moral themes. The program discussed here provides another instance of the family's carefully calculated and sophisticated use of artistic patronage to further its goal of maintaining power in Florence.97 Sarah Blake McHam, professor of art history, Rutgers University, edited Looking at Italian Renaissance Sculpture and contributed an essay on public sculpture to the volume. She is also the author of The Chapel of St. Anthony at the Santo and the Development of Venetian Renaissance Sculpture [Department of Art History, Voorhees Hall, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. 08901- 1248, mcham @rci.rutgers.edu]. Frequently Cited Sources Ames-Lewis, Francis, 1989, "Donatello's Bronze David and the

- 40. Palazzo Medici Courtyard," Renaissance Studies 3, no. 3: 235-51. , ed., 1992, Cosimo "il Vecchio"de'Medici 1389-1464 (Oxford: Clarendon Press). Coville, Alfred, Jean Petit: La question du tyrannicide au commencement du xve siecle (Paris: Auguste Picard, 1932). Hyman, Isabelle, Fifteenth Century Florentine Studies: The Palazzo Medici and a Ledgerfor the Church of San Lorenzo (New York: Garland, 1977). Janson, H. W., The Sculpture of Donatello, 2d ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979). The Statesman's Book of John of Salisbury, Being the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Books, and Selections from the Seventh and Eighth Books of the Policraticus, trans. and ed. John Dickinson (NewYork: Alfred A. Knopf, 1927). Ullman, Berthold Louis, and Philip A. Stadter, The Public Library of Renaissance Florence: Niccoli Niccoli, Cosimo de' Medici and the Library of San Marco, Medievo e umanesimo, vol. 10 (Padua: Antenore, 1972). Notes

- 41. Some of this research was first presented at the Wesleyan Renaissance Seminar in December 1994 and later revised in a paper given at the annual meeting of the Renaissance Society of America in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1996. I would like to thank the participants at both for their comments. I want to acknowledge especially the assistance of Professor Susan McKillop, who first brought to my attention John of Salisbury's reference to Judith in the Policraticus and for encouraging my research. I would also like to thank Professors Roger Crum, Tod Marder,John Paoletti, and Debra Pincus for their many helpful comments about earlier drafts of this essay, and Professors Jocelyn Penny Small and John Kenfield for their bibliographic assistance. Unless otherwise noted, translations are mine. 1. This interpretation was first advanced by Bonnie A. Bennett and David G. Wilkins, Donatello (Oxford: Phaidon, 1984), 85. Roger Crum, "Retrospection and Response: The Medici Palace in the Service of the Medici, c. 1420-1469," Ph.D. diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1992, considered the sculptures and paintings at the palace together, arguing that they should be seen as celebrations of the victory of humility over pride and of concord over discord. Crum argued more specifically that the David served to connect

- 42. the Medici to a general message of liberty and antityranny in an article that he brought to my attention after reading an earlier draft of this essay; see his "Donatello's Bronze David and the Question of Foreign vs. Domestic Tyranny," Renaissance Studies 10, no. 4 (Dec. 1996): 440-50. I thank him for his comments and the citation. I believe that the David and the Judith share this meaning and suggest in this essay literary and artistic sources that support the argument. 2. Christine M. Sperling, "Donatello's Bronze 'David' and the Demands of Medici Politics," Burlington Magazine 134 (1992): 218-24, published a manu- script she discovered in the Biblioteca Riccardiana, Florence, which records an inscription for the David as well as for the Judith and Holofernes and specifies that the Judith and Holofernes was located in the garden of the palace. Sperling argued that the manuscript could be dated between 1466 and 1469, and thus offered the earliest terminus ante quem for the installation of the Judith and Holofernes there. Sperling is the first scholar to analyze these points in relation to Donatello's sculptures. However, she was unaware that Paul Oskar Kristeller, IterItalicum, 2d ed. (London: Warburg Institute, 1967), 115, had earlier noted the citation in another manuscript in the Biblioteca Corsini, Rome, and that

- 43. Cecil Grayson, "Poesie latine di Gentile Becchi in un codice bodleiano," in Studi offerti a Roberto Ridolfi, ed. Berta Maracchi Biagiarelli and Dennis E. Rhodes (Florence: L. S. Olschki, 1973), 285-303, had published still another version of it that is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Grayson's demonstration that the manuscript was written by Gentile Becchi negates Sperling's attempt to argue that Filelfo was its author and, on that basis, date the David ca. 1430. Her other arguments, that the sculpture was commissioned in response to the Milanese threat to Florence at that time and that it relates in style to other sculptures by Donatello in the late 1420s and early 1430s, are taken from H. W. Janson, "La signification politique du David en bronze de Donatello," Revue de l'Art 39 (1978): 33-38, and are inconclusive. Crum, 1996 (as in n. 1), makes a more convincing case that, rather than alluding to a single threat of tyrannical aggression, the Medici disingenuously intended the David to suggest their defense of Florence from all danger of foreign or domestic tyranny, despite the reality that many considered their own rule tyrannical. Following Sperling's article, Francesco Caglioti, "Donatello, i Medici e Gentile de' Becchi: Un po' d'ordine intorno alla 'Giuditta' (e al 'David') di Via Larga," pt. 1, Prospettiva 75-76 (July-Oct. 1994): 14-22, published several

- 44. more versions of the 15th-century manuscript citation of the inscriptions on the David and on the Judith. As Caglioti noted, a date as early as 1464 is suggested by the context in which the record is found, a letter of condolence on Cosimo de' Medici's death (1464) written to his son Piero on Aug. 5, 1464. I thank Professor Caglioti for sending me a copy of this article and its sequels. 3. Luca Landucci, Diario fiorentino dal 1450 al 1516, ed. Iodoco Del Badia (Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1883), 121. 4. On the palace's architecture, see Hyman; and Brenda Preyer, "L'architettura del Palazzo Medici," in II Palazzo Medici- Riccardi di Firenze, ed. Giovanni Cherubini and Giovanni Fanelli (Florence: Giunti, 1990), 58-75. 44 ART BULLETIN MARCH 2001 VOLUME LXXXIII NUMBER 1 5. Other noteworthy features include the total nudity of the David, the conception of the Judith and Holofernes as a group in dramatic action, and the installation of life-size statues in a residential setting. To my knowledge, they are the first Renaissance examples of these phenomena. Caglioti (as in n. 2), 19-49, made the most recent contribution to the

- 45. controversy about the date and patron of the Judith and Holofernes. He argued that Donatello began the commission for Cosimo by 1457, put it aside during his sojourn in Siena (1457-61), and then completed the sculpture after his return to Florence and before his death in 1466. Previous historians divided into two camps about the commission, some followingJanson, 202-5, who, on the basis of Milanesi's reading of an elliptical reference regarding the purchase of bronze in Siena for Donatello in a document of 1457 (Siena, Archivio dell'Opera Metropolitana), contended that Donatello began the Judith and Holofernes as a civic commission for that city and then completed it for the Medici. Others, led by Volker Herzner, who retranscribed the document and read it differently, argued that it alluded to another commis- sion entirely, namely, a reliquary bust of Saint Giuletta ("Donatello in Siena," Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 15 [1971]: 178-85; and "Die 'Judith' der Medici," ZeitschriftfirKunstgeschichte43 [1980]: 159-63), and that the Judith and Holofernes commission had nothing to do with Siena, but was instead a Medici commission. 6. See Crum, 1992 (as in n. 1), for a comprehensive analysis of the palace. The frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli in the Medici Palace Chapel have received

- 46. much attention in regard to their political meaning; see the recent discussion and bibliography in Rab Hatfield, "Cosimo de' Medici and His Chapel," in Ames-Lewis, 1992, 221-44; Diane Cole Ahl, Benozzo Gozzoli (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 81-119, 219-20; and Roger Crum, "Roberto Martelli, the Council of Florence, and the Medici Palace Chapel," Zeitschrift fur Kunstgeschichte 59 (1996): 403-17. 7. The David stood at the center of the courtyard, which is on axis with the main portal of the palace and visible from the street. Its original base by Desiderio da Settignano has been lost, but it was described by Giorgio Vasari. Speculation has centered on its appearance and height, and how these affected spectators' view of the David from ground level in the courtyard and from the windows of the piano nobile of the palace. On these issues, see Ames-Lewis, 1989, 235-51, who first presented a reconstruction of the base; and Francesco Caglioti, "Donatello, i Medici e Gentile de' Becchi .... ," pt. 3, Prospettiva 80 (Oct. 1995): 15-58, where a more convincing reconstruction is offered. 8. Ames-Lewis, 1989, 240-41, first analyzed the uncertainties surrounding the original placement of the statue in the garden. Previously, scholars had

- 47. assumed that it was located on axis with the David in the courtyard; see Hyman, 195. Recently, Francesco Caglioti, "Donatello, i Medici e Gentile de' Bec- chi....," pt. 2, Prospettiva 78 (Apr. 1995): 22-55, expanded Ames-Lewis's arguments, contending that the Judith and Holofernes was located at the north end of the garden. Caglioti also challenged the long-standing interpretation that the Judith and Holofernes functioned as a fountain in the Medici garden. He argued that the base of the statue, which had been considered a replacement when the group was transferred to the Palazzo della Signoria, had been its base in the garden of the Medici Palace. In addition, he contended that the location of the Judith and Holofernes in that garden was not on axis with the David but instead at the north end of the garden and that a fountain without statuary stood on the site on axis with the David that historians had traditionally assigned to the Judith and Holofernes. See his diagram, 31. The recent restoration of the Judith and Holofernes revealed that the supposed waterspouts in the center of each relief of the three- sided base had never been opened, and confirmed the observation occasionally made earlier that the openings at the corners of the cushion on which Holofernes is

- 48. propped could have been plugged with now-lost bronze tassels, rather than serving as waterspouts; see Antonio Natali, "Exemplum salutatis publicae," in Donatello e il restauro della Giuditta, ed. Loretta Dolcini (Florence: Centro Di, 1988), 27. 9. On Cosimo's quasiofficial use of his palace as the site of government consultations, see Nicolai Rubinstein, "Cosimo optimus cives," in Ames-Lewis, 1992, 13, where the acerbic remarks of Giovanni Cavalcanti's Istoriefiorentine, ed. Guido di Pino (Milan: A. Martello, 1944), 20, are quoted: "... the governing of the city took place more at dinners and in private studies than at the town hall." The Terze rime, a panegyric written ca. 1459, recounted how Cosimo and Piero often entertained visitors at the palace; see Rab Hatfield, "Some Unknown Descriptions of the Medici Palace in 1459," Art Bulletin 52 (1970): 240, where fol. 26v is discussed. 10. On the wedding, see Hyman, 167. It was also available to receive guests after dinners, as for example when Galeazzo Maria Sforza visited in 1459, described in the Terze rime, 41v, in Hatfield (as in n. 9), 236; and in a letter in idem (as in n. 6), 227. 11. On these stone roundels, see Ursula Wester and Erika Simon, "Die

- 49. Reliefmedallions im Hofe des Palazzo Medici zu Florenz," Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 7 (1965): 15-91; on their relation to gems in the Medici collections, see Gennaro Pesce, "Gemme medicee del Museo Nazionale di Napoli," Rivista del Reale Istituto d 'Archeologia e Storia dell'Arte 5 (1935-36): 50- 97. 12. On the two sculptures of Marsyas, see Francesco Caglioti, "Due 'restaura- tori' per le antichita dei primi Medici: Mino da Fiesole, Andrea del Verrocchio e il 'Marsia Rosso' degli Uffizi," pt. 1, Prospettiva 72 (Oct. 1993): 17-42, and pt. 2, 73-74 (Jan.-Apr. 1994): 74-96. 13. "Victor est quisquis patriam tuetur. / Frangit immanis Deus hostis iras. / En puer grandem domuit tiramnum. / Vincite, cives!" For variant spellings, see Caglioti (as in n. 2), 39 nn. 30, 31. Sperling (as in n. 2) discovered the inscription connected to the David recorded in a 15th-century manuscript and introduced it into the art historical literature. 14. Alessandro Parronchi, "Mercurio e non David," in Donatello e il potere (Bologna: Cappelli; Florence: Il Portolano, 1980), 101-15, first suggested the reidentification of the statue as Mercury, andJohn Pope- Hennessy, "Donatel- lo's Bronze David," in Scritti di storia dell'arte in onore di Federico Zeri (Milan: Electa, 1984), vol. 1, 122-27, supported it. Ames-Lewis, 1989,

- 50. 238-39, and others have convincingly proposed that the identities of David and Mercury were instead conflated to create a multivalent image, different features of which could be seen from the ground and from the upper floor of the Medici Palace, thereby nuancing the sculpture's meaning to its audience. Patricia Ann Leach, "Images of Political Triumph: Donatello's Iconography of Heroes," Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1984, 53-154, most fully explored the underlying motives for merging David and Mercury in 15th- century Florence. 15. On the vexed question of dating, see, for example, Janson (as in n. 2), 33-38, who proposed a date of ca. 1430, seconded most recently by Sperling (as in n. 2). On the other hand, Francis Ames-Lewis, "Art History or Stilkritik? Donatello's Bronze David Reconsidered," Art History 2 (1979): 139-55, presented a serious case for a date as late as ca. 1460. For a convincing rebuttal of the literary and political arguments made by Sperling in favor of an early date, see Crum, 1996 (as in n. 1), 440-50. Although the weight of evidence now favors the late dating, the issue is not yet definitively resolved. 16. If, as some historians have argued, the purchase of bronze in Siena in

- 51. 1457 is connected with the Judith and Holofernes commission, then the statue was under way by that date. For further speculation about the commissioner and date, see n. 5 above. 17. Michelangelo's commission for the colossal David is the fulfillment of a project originally awarded in 1463 to Agostino di Duccio to carve a statue of the Old Testament figure for one of the buttresses of the Duomo in Florence. The contract was rescinded by the Opera del Duomo in late 1466, by which time Agostino had completed little, if any, carving. Charles Seymour, Michelan- gelo's David: A Search for Identity (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1967), 36-38, suggested that Donatello was providing the design for Agosti- no's execution and that Donatello's death in 1466 led to the contract's cancellation. If Donatello's bronze David dates as late as ca. 1460, then these two commissions are roughly coincident, but we know nothing useful about the intended appearance of Agostino's sculpture and cannot characterize its interpretation of David. 18. For the documents, see Giovanni Poggi, II Duomo di Firenze: Documenti sulla decorazione della chiesa e del campanile tratti dall'Archivio dell'Opera, ed. Margaret Haines, rev. ed., 2 vols. (Florence: Medicea, 1988) vol. 1, docs.

- 52. 425-27. On the history of the sculpture, see Janson, 3-7. 19. See Maria Monica Donato, "Hercules and David in the Early Decoration of the Palazzo Vecchio: Manuscript Evidence," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 54 (1991): 83-98. The inscription reads: ". .. statua Davidis marmorea cum funda in manu: cui adscriptum pro patria dimicantibus etiam adversus terribilissimos hostes deus prestat victoriam." This inscription is very similar to that in a late 16th-century guidebook by Laurentius Schrader, Monumentorum Italiae, quae hoc saeculo et a christianis posita sunt, libri quatuor (Helmstadt: Iacobus Lucius Transylvanus, 1592), fol. 78v, earlier discovered by Janson, 4. The difference lies in the last words, which in Schrader's text read "dii prestant auxilium." The pagan implications of the phrase in Schrader occasioned doubts among scholars that the inscription could have dated from the 15th century. The inscription uncovered by Donato refers to one god and removes that problem. 20. SeeJanson, 3-7. Other scholars have disputedJanson's arguments about the successive stages of David's identity and the statue's recarving, arguing that it was always intended for the Palazzo della Signoria and not recut. For these points and bibliography, see Luciano Bellosi, "I problemi

- 53. dell'attivita giova- nile," in Donatello e i suoi: Scultura fiorentina del primo Rinascimento, ed. Alan Phipps Darr and Giorgio Bonsanti (Detroit: Founders Society, Detroit Insti- tute of Arts; Florence: La Casa Usher, 1986), 47-54. 21. On examples of Judith with David, see Herzner, 1980 (as in n. 5), 164-69; and Mira Friedman, "The Metamorphoses of Judith," Jewish Art Journal 12-13 (1986-87): 235-39. 22. Modern theologians analyzing the text have pointed out its anachro- nisms and historical inconsistencies and argued that it was written as an allegory of the Jewish people to spur pride in their sense of identity. See The Book of Judith: Greek Text with an English Translation, Commentary, and Critical Notes, ed., trans., and annotated Morton S. Enslin and Solomon Zeitlin, Jewish Apocryphal Literature, vol. 7 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1972), 1. 23.Judith's role as a paragon of Christian virtues such as chastity, temper- ance, justice, fortitude, wisdom, and humility was established in the early Middle Ages by the Psychomachia of Prudentius, the very influential Christian epic written in 405. This spurred a large number of literary and visual interpretations of the theme, and an equally extensive secondary literature in

- 54. the modern period. For a brief synthesis of the Christian interpretations of Judith, see Mary Garrard, Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 282-89; and Frank Capozzi, "The Evolution and Transformation of the Judith and Holofernes Theme in Italian Drama and Art before 1627," Ph.D. diss., DONATELLO'S DAVID AND JUDITH: METAPHORS OF MEDICI RULE 45 University of Wisconsin, 1975, 3-22. For the additional connotations of situating a sculpture of this theme in a garden setting, see Matthew G. Looper, "Political Messages in the Medici Palace Garden," Journal of Garden History 12, no. 4 (1992): 255-68. For an exploration of the popularity of the theme, see the recent study by Margarita Stocker, Judith: Sexual Warrior Women and Power in Western Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). 24. The rim of roughly woven cloth, riding lower on her forehead than her veil, which has usually been discussed as an indication of Donatello's technique of casting from real cloth (see Bruno Bearzi, "Considerazioni di tecnica sul San Ludovico e la Giuditta di Donatello," Bollettino

- 55. d'Arte 16 [1950]: 119-23), is relevant to the tale ofJudith. It could hint at the sackcloth in which she and the otherJews of Bethulia dressed as they beseeched God to deliver them from Holofernes' siege of their town. It further indicates the modesty with which the widowed Judith typically dressed, disguised by the finery and jewels with which she covered herself to seduce Holofernes. 25. The three Bacchanalian reliefs on the statue's base reinforce this meaning; see Edgar Wind, "Donatello's Judith: A Symbol of 'Sanctimonia,'" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 1 (1937): 62- 63. 26. The medallion is described inJanson, 203. 27. Book ofJudith, 13: 6-10, 16: 19-20 (as in n. 22), 153, 175- 76: "And going to the bedpost which was at Holofernes's head, she took down from it his sword, and nearing the bed she seized hold of the hair of his head and said, 'Give me strength this day, Adonai God of Israel.' And with all her might she smote him twice in the neck and took his head from him. And she rolled his body from the couch and took the canopy from the poles.... Judith dedicated to God all Holofernes's possessions ... and the canopy which she had taken for herself from his bed, she presented to Adonai as a votive offering."

- 56. Generally, this more dramatic rendition is not common until the 17th century, as in paintings by Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi; see Garrard (as in n. 23), 290-91, 307-36. A rare early example is Guariento's version for the chapel of the Carrara Palace in Padua, now in the Musei Civici, Padua (first cited by Herzner, 1980 [as in n. 5], 144-45). 28. An anonymous early 16th-century painting of the Execution of Savonarola in the Museo di S. Marco, Florence, records the group on the ringhiera, or rostrum, outside the Palazzo della Signoria after 1495, representing it as entirely gilded. Conservation reports indicate that it was not, but the painting's exaggeration makes clear the brilliant impression it must have had in the sun; seeJanson, 201. 29. "Regna cadunt luxu, surgunt virtutibus urbes: / Caesa vides humili colla superba manu." 30. "Salus Publica. Petrus Medices. Cos. fi. Libertati simul et fortitudini hanc mulieris statuam, quo cives invicto constantique animo ad rem publicam redderent, dedicavit." 31. Dante, Inferno, canto 4, line 123, and canto 34; Paradiso, canto 6. 32. In Boccaccio's unfinished commentary on Dante's Commedia, he de-

- 57. scribed how Caesar seized control of the government against Roman law and made himself perpetual dictator. See Boccaccio, Il Comento alla Divina Commedia, ed. Domenico Guerri, Scrittori d'Italia, vols. 84-86 (Bari: Giuseppe Laterza and Sons, 1918), vol. 1, 205, vol. 2, 49. 33. Harmodios and Aristogeiton succeeded in slaying only Hipparchos, the younger brother of the tyrant Hippias. The significance of the date of the killing was given additional resonance by Pliny in the Natural History, who claimed that it coincided with the day on which the kings were expelled from Rome. See the quotation of the passage in n. 38 below. 34. There are authoritative accounts of the group by Sture Brunnsaker, The Tyrant-Slayers of Kritios and Nesiotes (Lund: Hakan Ohlssons Boktryckeri, 1955); and Michael W. Taylor, The Tyrant Slayers: The Heroic Image in Fifth Century BC Athenian Art and Politics, Monographs in Classical Studies, 2d ed. (Salem, N.H.: Ayer, 1981). For a succinct analysis with bibliography, see Sarah P. Morris, Daidalos and the Origins of Greek Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 297-308. For a recent account of the monument in relation to its site, see Ulf Kenzler, Studien zur Entwicklung und Struktur der griechischen Agora in archaischer und klassischer Zeit, Europaische