Pashto phonetics

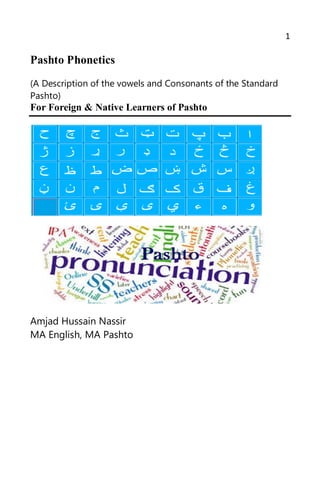

- 1. 1 Pashto Phonetics (A Description of the vowels and Consonants of the Standard Pashto) For Foreign & Native Learners of Pashto Amjad Hussain Nassir MA English, MA Pashto

- 2. 2

- 3. 3 Pashto Phonetics (A Description of the vowels and Consonants of the Standard Pashto) For Foreign & Native Learners of Pashto Amjad Hussain Nassir MA English, MA

- 4. 4 Foreword All glory be to Allah, the creator and sustainer of the universe and all what is beyond it. It is my pleasure to put up before you the most wanted book on Pashto Phonetics keeping in view two major needs; firstly, the demand of my students wherever I have taught them; secondly, there is no book available in the country specifically on Pashto Phonetics, the main reason being that Pashto is the language of the inhabitants of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, and the National Language of the country is Urdu, thus the need at national level for the description of Pashto has not been felt by the intellectuals or people in the power corridors, their main focus being on Urdu and, of course, English, since the official correspondence of the country is mostly in English. My experience of teaching for the last seventeen years has taught me a lot of things about the needs and psyche of the Pakistani students; their aims and objectives in getting education; the trust of their parents in them for achieving good grades in their studies; and the support, both financial and moral, from parents, as they want their children to be educated, and prove to be good citizens of Pakistan. In my opinion, education makes good humans; humans with the requisite skills not only to benefit their own self and families, but also the entire humanity at large. I have learnt from scholars in psychology that we dream in our mother tongue because our subconscious is primarily preoccupied by our mother tongue, since our first ever encounter after being born in the world is with our mother tongue, which remains there till death. It is easier for us to talk in mother tongue, most often without making any conscious effort to think and speak in it. This is a long debate which I do not want to indulge in at this point in time, but our attitudes are determined by our perception of the world and our behavior is determined by our attitude towards the world. If want to be positive to the people around us, a positive attitude is a prerequisite for this and humanity demands from us that we behave well. Education makes us good humans, and true education, in the point of view of scholars, is that which is achieved in a natural environment rather than by rotting or continuous drills and practices, which we can learn through practice, but which we may or may not like to learn. Keeping the idea limited, there is no denying the fact that education acquired in mother tongue is more effective and long

- 5. 5 lasting than one acquired in any other language. It is on account of this fact that I focused my attention to the study of my mother tongue, Pashto, and started exploring the various facts about it, one among which is the phonetics of Pashto, which is an area of my interest. Other aspects of Pashto such as syntax, semantics, and morphology etc are of course a huge area to be explored. Not to mention the sociolinguistic ambit of Pashto language, which also has a tremendous scope for being explored by scholars and researchers in linguistics. The book is open to you for reading with a hope that you benefit from its reading. I would very much like to have your feedback on the book in case you found technical, typing, thematic or semantic errors. Any positive comments would not only benefit me but also the readers at large which shall come in the form of revisions in the next edition. Any comments, suggestions/feedback or review of this book can be sent to amjadnaasir@gmail.com. I am praying for your future success with hope that you will benefit from reading the book. Amjad Nassir

- 6. 6 Acknowledgments Alhamdulillah! To the almighty, for bestowing upon me the blessings of knowledge. Thanks to the teacher of teachers, the leader of leaders, the guide of all guides and the prophet of all prophets, Muhammad peace be upon him, who taught me how to live and how to please my creator. After him, I am truly indebted to all my teachers who taught me what I know; my mother, who taught me what I do; and my students who taught me what I must teach. Equally I am thankful to my wife, Muneeba Amjad, who has been so much supportive towards me in my intellectual endeavors. I am thankful to my son Ryan, who has always taught me how to be inquisitive and how to pursue things I never knew before. I am thankful to all those friends who have given me moral support in any intellectual pursuit I have been making so far. I am highly indebted to the English authors Peter Roach, Daniel Jones, O’Connor and John Lyon who inspired me for reading about language and linguistics and particularly phonetics and phonology. I am especially thankful to Noam Chomsky, for inspiring me to study the structure of language in general and that of Pashto in particular. Indeed his scholarship will go a long way in guiding my thoughts as long as I stay in touch with the study of language. My teacher Professor Dr. Aurangzeb, who is not in Pakistan, is missed every moment I talk of language, for he was the first teacher who inspired me for pursuing my studies in linguistics. My other teachers, Professor Muhammad Hussain, Prof Dilawar Said, Prof Fazal-e- Sadiq who taught me at Government Degree College, Dargai, My teachers and mentors, Sir Dr. Zulfiqar Ali, Dr. Amjad Saleem, Dr. Muazzam Shareef, Dr. Yaser Hussain, Dr. Riazuddin and other teachers, I will be unable to count in this little space, all deserve my gratitude and respect, who have guided me all the way down to this moment, and without whose support, I could not have been able to learn. I pray for all the near and dear ones, my friends, relatives and especially my children, Ryan Nassir, Mehwish Gulalay Amjad, Affan Taimur Nassir, Sehrish Gulalay Amjad, and the little Sannan Abdullah Nassir, who make my life beautiful by their constant smiles around the year. amjad nassir

- 7. 7 ABOUT THIS BOOK This book is intended for all those readers who have interest in the study of phonetics, though it is a specialized subject in linguistics. It is by no means an exhaustive book which will serve the need of advanced level readers. It is brief, and its contents are devised for self-study as well as for study in groups of peers. It can also benefit teachers of Pashto Language if they want to use it in class room situations. Effort has been made to make the contents of the book as simple as possible. One interesting fact about this book is that it is placed in a context which the readers will find more local rather than international. My experience of teaching at different levels of academics has dawned upon me certain facts which are more of psychological nature and which I cannot count in here, but which I definitely had in mind when I embarked upon the journey of conceiving this book in the first place, and later on, preparing this book. I felt the need to work out on this book due to many reasons. One reason is that I could not get any book on Pashto phonetics in any library. There are many books available in the market about English phonetics and phonology and my reading has inspired me to make an attempt for writing on Pashto Phonetics. The non-availability of books of Pashto Phonetics may be attributed to various reasons. In my opinion the reason might be that the readers of Pashto language are not the readers of English and vice versa. This book will serve as a bridge between the two languages because its medium is English while the language it describes is Pashto. I hope I will be right to claim that this book will be the very first book of its kind to have been written. Since it is my first attempt, I believe it will be deficient in many ways. But keeping restricted to our limitations does not mean we should quit attempting new

- 8. 8 things. I have made an attempt, which may be poor, weak, and wanting more knowledge and scholarship, but I did make an attempt, no matter how weak or poor. Every new experience is hard and non-conclusive. The fact that this book is not exhaustive is accounted for by the very limited contents of this book. It focuses only on phonetics of Pashto. The Phonology of Pashto, the segmental and supra-segmental features are left for the next edition of the book. I hope this book will inspire scholars, and students like me, to make further greater attempts in future. This book will help those students a great deal who want to clarify their key concepts in the area of phonetics. This book is ideal for those students who are the beginners in the subject because its contents are few, its language is simple and examples are easy. It is equally of value to those who have a lot of knowledge about the subject but who need material to teach from. The best way to use book is to give sufficient time to each session. After having read the session, the students must browse through the internet for expanding the scope of their understanding by finding the relevant examples from other languages. once they grasp the topic completely, they should move to the next session. This approach will help them learn more effectively. For foreign learners of Pashto, this book will be of help to them in learning the phonetic aspect of Pashto language, which will help them a great deal in learning correct pronunciation, as the standard symbols of IPA have been used and if they know how to use IPA symbols, they will definitely learn how to use the same symbols in learning correct pronunciation of Pashto sounds. For teachers of Pashto language, this book, it is hoped, will prove to be a good read. It will provide them the way forward for how to go about teaching phonetics to the students of Pashto language and linguistics in the classroom which will be of great use in their professions.

- 9. 9 Last but not the least, I would like to mention here that this book is my solo flight and I had no support from any organization or department. It was my love for the subject that had been driving me to this day and which urged me to do the research work and publish it on my own. My frequent visits to the department of Pashto, The Pashto Academy University of Peshawar went futile. I volunteered to design a course for the Pashto Academy and the Department of Pashto for the MA Pashto Previous and Final classes and expressed my willingness to prepare books of Language and Linguistics and Pashto Language Teaching to be taught at Masters level but my generous offer fell on deaf ears. The Students of Pashto Academy as well as the Pashto Department are not very lucky to have missed this opportunity offered to their department by a volunteer, and I believe the next generation will be deprived of the studies in Linguistics in the future. It is high time for the Academy as well as Pashto Department to introduce courses in General Linguistics and Pashto Language Teaching, otherwise too much water has already flown uselessly down the bridge. I am always willing if my help in academics i.e. curriculum designing, course material preparation etc. are required but it is the need of the hour to develop curriculum for Pashto language and literature on modern lines. Towards the end, I would like to inform my readers with utmost honesty, that being a Pukhtoon I have realized that the Pukhtoons, as a nation, are mentally very sharp and highly critical, though the criticism takes negative and destructive form at times. I have observed in them that if one Pukhtoon becomes rich, the other is jealous without any reason and criticizes him in such words and phrases that the rich starts wishing to be poor. The similar is the case with a Pukhtoon who becomes a scholar. The other Pukhtoon scholar, if he has become one by chance or by personal efforts, make fun of him by calling different names to the effect that he starts wishing to be

- 10. 10 illiterate. In my personal opinion, this social phenomenon among the Pukhtoons has caused more trouble and rather destruction for the community at large. If one makes an attempt to contribute to knowledge by making any research work etc. majority of the Pukhtoons will try hard not let the gentleman achieve his academic goals. No scholar of English and Pashto among the Pukhtoons was ready to even give a proof reading to this book which is a fact that I will always remember about my Pukhtoon fellows. Therefore, my perception about the Pukhtoon intellectuals is utterly pessimistic. It is my perception, which might be wrong, but I believe the illiterate Pukhtoon is more helpful, more hospitable, more sacrifice maker for fellow beings and more responsible than these educated and so called intellectual Pukhtoons, who get education not to become good humans, but rather for fame and popularity among the majority of the Pukhtoons who are very simple, innocent, brave, courageous, candid, loving, caring and highly cooperative by nature. In preparation of this book, none of my friends, fellow men helped except just a few, who did not extend any physical help but rather emotional support that ‘Go man, you can do the job’. The rest, this book is purely my own attempt and the mind of one individual is limited. It will be faulty, poorly ordered, lacking scholarship and needs a lot of improvement but it is one man’s endeavor and I, as a human being, admit my weaknesses but I don’t want to live an apologetic life due to this reason. I made the attempt, and I always will.

- 11. 11 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction Chapter 2 The Phoneme, phonetics and phonology Chapter 3 The Production of Speech Sounds Chapter 4 The International Phonetic Alphabet Chapter 5 The Consonants of Pashto Chapter 6 The Vowels of Pashto Chapter 7 A Note for the Teachers of Pashto Language

- 12. 12 Chapter 1 Introduction Pashto language, whose speakers prefer to speak and write it as Pukhto, is the language of the Pashtuns (Preferably the Pukhtoons, as they call themselves, and the Afghans as the Persians call them or the Pathans, as the Indians call them). It is known in Persian literature as Afghani and in Urdu and Hindi literature as Paṭhani. Speakers of the language are called Pashtuns or Pakhtuns and sometimes Afghans or Pathans by people outside the province in which they live. Pashto is one of the two official languages of Afghanistan (Hallberg 1992, Penzle 1955). The total number of Pashto-speakers is estimated to be 45–60 million people worldwide. Other communities of Pashto speakers are found in Tajikistan, and further in the Pashtun diaspora. Sizable Pashto-speaking communities also exist in the Middle East, especially in the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, North- eastern Iran. According to the latest estimates, it is spoken by some eight million people in Afghanistan, six million in Pakistan, and about 50,000 in Iran. Pashto is thus the second in importance among the Iranic languages and in Afghanistan the official language, beside Darī. The Pashtun diaspora speaks Pashto in countries like the US, UK, Thailand, Canada, Germany, Australia, Japan, Russia, New Zealand, and the Scandinavian countries like the Netherlands, Sweden, etc. In Pakistan, Pashto is spoken as a first language by about 35-40 million people – 15.42% of Pakistan's 208 million population. It is the main language of the Pashtun majority regions of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern Baluchistan. It is also spoken in parts of Mianwali and Attock districts of

- 13. 13 the Punjab province and in Islamabad, as well as by Pashtuns who live in different cities throughout the country. Modern Pashto-speaking communities are found in the cities of Karachi and Hyderabad in Sindh. The two official languages of Pakistan are Urdu and English. Pashto has no official status at the federal level. The primary medium of education in government schools in Pakistan is Urdu, but from 2014 onwards, the Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has placed more emphasis on English as the medium of instruction. English-medium private schools in Pashto-speaking areas, however, generally do not use Pashto. The imposition of Urdu as the primary medium of education in public schools has caused a systematic degradation and decline of many of Pakistan's native languages including Pashto. This has caused growing resentment amongst Pashtuns, who also complain that Pashto is often neglected officially and if the attitude of the central government towards Pashto remains the same, there is a danger of Pashto becoming an extinct language. In Pashto, most of the native elements of the lexicon are related to other Eastern Iranian languages. However, a remarkably large number of words are unique to Pashto. Post- 7th century borrowings came primarily from the Persian and Hindustani languages, with some Arabic words being borrowed through those two languages, but sometimes directly. Modern speech borrows words from English, French and German. A number of sources discuss various dialect divisions within the Pashto language. One distinction which is almost universally mentioned in these sources is the distinction between hard and soft Pashto. On this topic Grierson says, “Over the whole area in which it is spoken, the language is essentially the same.” This will to some extent

- 14. 14 be evident from the specimens which follow. Such as they are they show that, while, as we go from tribe to tribe there are slight differences in pronunciation and grammar, the specimens are all written in various forms of what is one and the same language. Two main dialects are, however, recognized, that of the north-east, and that of the south-west. They mainly differ in pronunciation. The Afghans of the North-east pronounce the letter ‘kha’ and those of the South- west pronounce them ‘Sha’ (1921:7). Another statement determines where Grierson thought these two varieties to be spoken: The North-Eastern dialect is spoken in the district of Hazara, and over the greater part of the districts of Peshawar and Kohat, but in the two latter the members of the Khatak tribe use the South-Western dialect. In the districts of Bannu and Dera Ismail Khan the SouthWestern dialect is universal (1921:10). In yet another statement, when speaking about South Western Pashto speakers besides the Khataks, Grierson says: Other speakers of the South-Western dialect are the remaining Pathan tribes of Bannu, among whom the principal are Marwats, the Nyazis, the Bannuchis, and the Wazirs (Grierson 1921:69). Many other writers have also pointed out this major two part division between Pashto varieties, but in later writings a finer distinction based on pronunciation is delineated. One such writer is D.N. MacKenzie, who, in his 1959 article entitled ‘A Standard Pashto, distinguishes four dialect areas based on five different phonemes. These are: South-west (Kandahar), South Pashto, east (Quetta), North-west (Central Ghilzai), and North-east (Yusufzai) (1959:232) In addition to the unique qualities found in Waziri, it also seems that other Pashto varieties exhibit qualities that are not specifically revealed by the simple four-part division mentioned above.

- 15. 15 Morgenstierne says: ‘… the dialectal variety of Pashto is far greater than that of Baluchi. And among the Afghans, the nomadic Ghilzais and the comparatively recent invaders of Peshawar, Swat, etc. show the least amount of dialectal variation, while the central part of Pashto speaking territory is the one which is most split up into different dialects (1932:17). The lexical data as displayed by the Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Vol IV, shows that the Northern Pashto, as called by some researchers as the Eastern or Northeastern Pashto includes the word list locations of Peshawar and Charsadda in District Peshawar, Mardan and Swabi in District Mardan, Madyan and Mingora in District Swat, Batagram, Baffa, and Oghi in District Mansehra, and Dir in District Dir and with only a few exceptions, all of the similarity counts between these locations were 90 percent or above. In addition, within this larger Northern group there were sub-areas of greater similarity. For example, Madyan and Mingora, in District Swat, have 99 percent lexical similarity; Batagram, Baffa, and Oghi share 99 to 100 percent lexical similarity; and Peshawar and Charsadda are 97 percent similar. In contrast, similarity percentages between Northern locations (including tribal locations) and nearly all of the Southern-group localities were in the 70s or low 80s. Many percentages between the two major groups were in the 70s. The morphological differences between the most extreme north-eastern (i.e. the Peshawari dialect) and south- western dialects (i.e. the Kandahari dialect) are comparatively less considerable. Pashto is spoken slightly differently from place to place (e.g., Swat, Peshawar, Hazara), but the differences do not appear to be very great. However, there is a marked difference between the extreme north and extreme south varieties both lexical and phonological. The criteria of dialect differentiation in Pashto are more of a phonological nature than

- 16. 16 lexical or morphological. The differences other than phonological are not so great as to divide Pashto as a language into contrasting dialects. With the use of an alphabet which disguises these phonological differences the language has, therefore, been a literary vehicle, widely understood, for at least four centuries. This literary language, in the words of D. N. MacKenzie (1959), has long been referred to in the West as 'common' or 'standard' Pashto without, seemingly, any real attempt to define it. On this account it seems appropriate to attempt to define standard Pashto in more concrete phonemic terms than any adaptation of the Arabo-Persian script allows it to stay as a distinct language with a definite standard dialect and a number of other local varieties. Dialects, particularly of the north-east, have abandoned a number of consonant phonemes but have generally confirmed the vowels in their morphological positions. It is an obvious inference that an older stage of Pashto, combined a 'south-western' consonant system with a 'north-eastern' vowel phoneme system. It is this conceptual phonemic system, therefore, which is reflected in the verse of the classical period of Khushal Khan and Rahman Baba. Apart from the evident value of this 'Standard Pashto', in its discreet native dress, as a universal literary medium among Pashtuns, it appears to have another important application. It permits the description of Pashto morphology in more accurate and universal terms than does any single dialect. Moreover, once established, by a comparison of the main north-eastern and south-western dialects, it may well serve as the basis for a simple description of the regular phonetic divergences of other dialects. Of the 36 consonant signs of the standard alphabet, D. N. Mackenzie states, seven, appear almost exclusively in loanwords of Arabic origin and represent no additional phonemes of Pashto. They are mere ' allographs ', marked in the transliteration by a subscript line. Here D. N. Mackenzie seems to have left a gap. The current phonemes of standard Pashto may or may not be the same as mentioned by

- 17. 17 him and it needs further investigation, which this study will attempt to find out. Pashto is an ancient language that is written in Perso- Arabic script. Its vocabulary contains words borrowed from Ossete, Persian, Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu and other regional languages of Pakistan, also some Indo-Aryan languages. It is considered to be in close relation with Persian but there are certain features in Pashto that are not found in Persian e.g. there are certain consonants and vowels in Pashto that are not found in Persian like retroflex oral stops []ټ and [,]ډ retroflex flap [,]ړ retroflex nasal []ڼ etc. Secondly in Persian, there is no gender and noun case, nouns have only categories of definiteness and number but in Pashto there is. Stress pattern is also different, in Pashto the emphasis, again unlike Persian, is not on the last syllable, but can vary. This freedom of shift from one syllable to another plays a very important grammatical role in Pashto and allows it to give different meanings to same words. Due to these facts many researchers have suggested that origin of Pashto is not Persian rather it is either Ossete or a language from which Ossete has originated though Pashto has borrowed a number of lexical items from Persian. As far as phonetical borrowings are concerned, Pashto has borrowed phonemes from Arabic in exact form and shape. The main reason being, Pashto is spoken by people, who accepted Islam as a community, and the reading of the holy book, Al Qur’an or the Qur’an is obligatory for everyone who believes in Islam. The reading of the Qur’an was impossible without Arabic in the days when the Qur’an was not translated in languages other than Arabic. Even now, its reading is mandatory in Arabic for spiritual satisfaction and pleasure of the Almighty Allah. Let us examine an excerpt of the Yusafzai Pashto as recorded on page 32 of Vol X of the Linguistic Survey of India by Sir George Abraham Grierson who placed the Yusafzai Dialect in Vol X for the reason that this dialect belongs to the Iranian Family, the specimen of which he included in the book

- 18. 18 and the following excerpt was included with the courtesy of Sir Herold Deane. A snap shot of the excerpt of the Yusafzai Dialect is shown here below: The same paragraph, if transcribed in today’s Peshawari Pashto, it will be reading as follows: برخه خپله له ما پالره چې ووېل ته پالر خپل کشر هغه نو وو زامن دوه سړي يو د کشر پس ورځې څو يو .وويشو دواړو په جائېداد خپل هغه نو .راکړه نه مال د په مال خپل يې هلته او .وکړو کوچ يې ته ملک لرې يو او کړل جمع څۀ هر زويي خال يې ټول چې نو .والوزولو مستۍراغے قحط يو باندې ملک هغه په نو کړو ص او .شو نوکر سره سړي معتبر يو وطن هغه د او الړو هغه نو .شو تنګ هغه او

- 19. 19 په سره خوشحالۍ په به هغه او .اولېګو ته پټو خپلو دپاره څرولو د خنزيرانو د هغه پيا .ورکول نۀ هيچا خو .وه کړې ډکه ګېډه خپله خوړل خنزيرانو چې بوسو هغه چډوډۍ شان ښۀ په نوکران پالرڅومره د ځما چې وئېل ويې نو شو خود په ې وايم به ورته او .ورشم به له پالر خپل او پاڅم به زۀ .مرم لوګې د زۀ او .مومي زوے ستا چې يم نۀ الئق ددې او .هم ستا او ده کړې ګناه خداے د ما پالره چې پاڅېدو هغه او .واچوه مې کښې نوکرانو په خو .شمخو .راغے له پالر خپل او وروزغلېيدو او وکړو پرې يې ترس وليدواو پالر خپل نو وو بېرته ال هغه چې او خداے د ما پالره چې ووئېل ورته زويي او .کړو يې ښکل او وتو ورترغاړه نوکرانو خپلو يې پالر ولې .شم زوے ستا چې يم نه الئق ددې نو .ده کړې ګناه ستا جام ښه چې ووئېل تهکړئ الس په يې ګته يوه او .واغوندئ يې ته دۀ او راوړئ ه ځکه .وکړو خوشحالي او وخورو ډوډۍ چې راځئ او .کړئ ښپو په ورته پڼې او هغوي او .دے شوے پېدا او ؤ ورک .دے شوے ژوندے او ؤ مړ زوے زما دا چې .کړه جوړه خوشحالې ت کور او راغے چې او .ؤ کښې پټي په زوے مشر هغه د اوسنزدے ه او وکړو اواز يې ته نوکر يو نو واورېدو يې اواز ګډېدو د او سرود د نو شو رور ستا چې ووئېل ورته هغه نو دے؟ مطلب څه ددې چې وکړه ترې يې پوښتنه موندلے جوړ روغ يې هغه چې ځکه .دے کړے خېرات دې پالر او دے راغلے را يې پالر نو .تللو نۀ دننه او شو مرور هغه نو .دےورته يې منت او اووتو ستا ما کالونه ډېر دومره ګوره چې ووئېل ته پالر کښې جواب په هغه نو .اوکړو ما چرته تا هم بيا او کړے مات دے نۀ حکم ستا مې هيچرې او دے کړے خدمت .وې کړې خوشحالي سره دوستانو خپلو د پرې ما چې دے نه راکړے چيلے يو له مال چې زوي ستا دا چې خو ولېتا نو راغے دے کړے خراب ډمو په درته يې ځما او يې سره ما همېشه ته زويه چې ووئېل وراه هغه نو .ورکړله مېلمستيا ورته دا چې ځکه شو خوشحاله او وکړو ښادي مونږ چې وو مناسب دا .دي ستا څۀ هر .دے شوے موندلے ؤ ورک او .شو ژوندے بيا ؤاو مړ رور ستا This transcription of current day Pashto is the current trend in writing Pashto in the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa Province, which has been, or is supposed to be officially, adopted after the Pashto Academy, the University of Peshawar announced that a standard for writing Pashto is the need of the day and must be adopted for the future literary and linguistic works in Pashto Language and Literature. This transcription is to be made the

- 20. 20 standard transcription due to the fact that almost three decades ago, the Barra Gali Conference held on July 11 and 12, 1990, which was attended by famous scholars, writers, linguists and researchers of Pashto Language and Literature from Northern and Southern Pukhtunkhwa including Afghanistan, the entire Khyber Pukhtunkhwa Province and the northern areas of Baluchistan, where Pashto is spoken as first language, stressed the importance of adopting a standard and uniform transcription system in order to bring about uniformity and consensus among the writers of Pashto. A number of decisions, total seventeen decisions to be more precise, were taken unanimously by the delegates (copy of the minutes of the conference attached). The purpose of the conference was to mutually decide upon the alphabets of the Pashto language to take conclusive steps in order to make a standard phonetical and phonological system of the Pashto language, not only for indigenous speakers and users of Pashto but also to make the job of the foreign learners of Pashto easy. In fact certain linguists and literary scholars still have reservations about a few sounds of Pashto which are not, according to them, precisely transcribed, or proposed to be transcribed, by the scholars who participated in the Conferences held from time to time, about taking conclusive steps, and reaching to conclusions about the transcription about the alphabets of Pashto language. Let us see another paragraph in Peshawari Pashto which is written in current standard transcription of Pashto as approved by the Pashto Academy, University of Peshawar, the institution who is responsible for ensuring to serve the Pashto Language and Literature in any capacity. The paragraph reads as follows: نو .دے زوړ ډېر ته لوري يو کول بحث دا نه؟ که او دے پکار مقصد څۀ ادب ده پوهان چې ځکه .دي ضروري پوهيدل دے په او ذکر ددے هم اوس ته لوري بل د هغې د او ليک خپل د هغه نو وي نۀ پوهه ښه دې په ليکونکے يو که فرمائي خپل نه نظريه بشپړه کيدونکې پيش سره طور واضحه يو هيچرے حقله په اظهار د چې او .شي کولې وړاندې ته اورېدونکو او لوستونکو نورو نه او ته ځان

- 21. 21 نه اثر پوره پوره هم چرته لوستونکي په نو وي نه واضحه نظريه خپله ليکونکي خو ليکوال چې وي پکار ستائيل ټول هله دوزخ جنت ،جهان ،ژوند .پرېوتلے شي ازادۍ په رائې خپله کنه؟ ده منظوره ته تاسو .کنه پوهيږي هم خپله په پرې وي نه ګيله به زمونږ .کوئ مۀ غندنه خو وي څه هر که عنوان ...راکړئ This excerpt contains the Pashto alphabets which are used in the Peshawari dialect which is spoken in the capital of the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province, Peshawar and the adjacent districts of Charsadda, Mardan, Noshera, Kohat, Swabi and by speakers of the tribal regions of District Khyber, District Bajaur and Muhmand erstwhile Khyber Agency and Muhmand Agency and Bajaur Agency. The regions such as District Swat, Dir Lower and Dir Upper, Buner and Malakand which are closer to these adjacent districts of Peshawar and Swabi, also speak the same Peshawari Dialect with slight variations of pronunciation and vocabulary which are mutually comprehendible for the listeners of the entire province. It is perhaps this reason that the electronic and print media makes use of this dialect. Few geographical, historical and literary facts oblige me to consider the Peshawari Pashto as the dialect of Pashto which is the most important dialect of Pashto and it is the dialect which must be designated as the Standard Dialect for both the native and foreign learners of the Pashto language. Other than the historical and literary reasons which will follow later, certain geographical statistics show that the Peshawari Pashto is the dialect of Pashto which is equally understood by all speakers of the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province and is spoken by most of the residents of the region where Pashto is the mother tongue of the speakers with the exception of the residents of the few southern districts, which in themselves have a variety of the Pashto language with certain variations of grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. According to the census of 2017, after the

- 22. 22 merger of erstwhile tribal agencies, and FR regions the total population of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province is 35,525,047 out of which 21,081,158 (59%) population of the three divisions namely Malakand, Mardan and Peshawar divisions speak the Peshawari Pashto while the rest of the population i.e. 14,443,889 (41%) which reside in other divisions of the province, the majority of whom understand the Peshawari Pashto, although the speakers of the Peshawari dialect are lesser in number. It must be kept in mind that the speakers from the other divisions, who have frequent interaction in the field of business, education or who keep family relations or friendships with people in the Peshawar or its adjacent regions, understand the Peshawari Pashto, since it is capital of the province, and off course, carries historical, political and financial significance not only for the people of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa but also for the country and the world at large. This book considers the Peshawari Pashto as the Pashto spoken and understood by all those Northeastern speakers of the Pashto language who reside in or around the Peshawar region including the Peshawar division and the adjacent divisions of Mardan and Malakand. Apart from the districts of Peshawar Division, all the districts of Mardan and Malakand division also speak the same Peshawari Pashto, though with slight variations of pronunciation, but not necessarily those of grammar and vocabulary. The districts of Swabi, Charsadda, Noshera, Buner, Swat, Malakand, Dir Upper and Dir Lower, Bajaur, Mohmand, Khyber, and Kohat have the same dialect of Pashto which is spoken and understood alike. The common observation that language changes after each twelve to fifteen kilometers is a reality yet to be proved thought, these districts are spread well

- 23. 23 over a radius of 25,620 sq. km out of the entire area of the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province which is 101,741 sq km after the merger of the erstwhile FATA. Research about the exact number of those speakers who can speak or understand the Peshawari Pashto, particularly after the merger of the erstwhile FATA region into the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province, is an open option for any independent researcher. Due primarily to lack of time, testing was not done in the reverse direction — testing the Quetta story in Yusafzai/Peshawar territory. This is something which probably should be done in the future to verify that Yusafzai really is more widely understood than the Quetta dialect. Apart from geographical significance, the Peshawari Pashto carries historical as well as literary significance when it comes to describing a dialect of Pashto which is understood by all and used by majority of the Pukhtoon population. As mentioned earlier, a huge population of the Pukhtoons is living abroad in different parts of the world as well. Their channel of communication with their community back home is either the internet or the TV channels, which are a formal mode of communication and for the formal mode, the Peshawari Pashto is utilized by the TV Channels. We will come to this point later in our discussion. Let us briefly discuss the various reasons for why the Peshawari Pashto be considered as the standard dialect for the native as well as the foreign learners of Pashto. The oldest form of poetic composition in Pashto literature is the ‘Tapa’. It is said that Pashto poetry was born out of the womb of Tapa which is a literary form that has a very simple metrical composition but a very comprehensive and pregnant thematic make up. It is one of the oldest forms of folk literature and is

- 24. 24 traced by historians to the pre-Greek era. The first ever Tapa recorded in the books of history which is: سپوږميخيژه را وهه کړنګ ه ريىبينه ګوتې کوي ؤَلـ ګلو ده مـى يار Spogmaya Krung Waha Rakheeja Yaar Me Da Gulo Lao Kawi Gutey Rebeenaa And is translated into English as follows; O Moon! Come out soon with jingle and light up the sky, My lover is out at midnight to harvest flowers who might hurt his fingers in the dark. If we look at the syntactic structure of the above Tapa, it is written in the Peshawari dialect although it was not known in those days that the Peshawari dialect will ever exist. Another Tapa which is recorded about a 1000 years ago, by famous historian Khursheed Jahan, when the Armies of the Great Sultan Mehmood of Ghazna came to India in their series of battles which they won one after the other. There was a commander in his armies by the name ‘Khaalo’ who belonged to the Gomal Pass, in the current Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. His beloved fiancé was reported to have uttered the following Tapa when she came to know that the Armies of Mehmood of Ghazna are about to cross the Gomal Pass in a couple of days:

- 25. 25 راشي لښکرے خالو د چې ځمه له ديدن يار خپل د ته ګومل به زه Che Da Khaalo Lakhkaray Rashi Za Ba Gomal Ta da Khpal Yar Deedan La Zama Which can be translated into English as: When the Armies of ‘Khaalo’ would reach, I would go to the Gomal Pass to meet my lover there. Although it was sung by a lady of the southern districts of the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa and it should have been in the southern dialect but, against our expectations, it is in the Peshawari dialect. Similarly, a book named ‘Roohi Sandary’ at the Pashto Academy, University of Peshawar, contains about 26000 Tapas and hardly a few might be in the dialects other than the Peshawari dialect. Thus historically, the very beginning of Pashto literature is woven into a dialect which was a standard, because every speaker and every writer knew that it is the dialect which is understandable for every speaker of Pashto. This fact is narrated by Morgenstierne when he says that the orthography of Pashto was fixed in the 16th century, the distinction between ش /ʃ/, ژ /ʒ/ and خ , ږ seems still to have been preserved even among the north-eastern tribes, who were probably the creators of Pashto literature (1932:17). The first ever recorded book of Pashto which exists, is Bayazid Ansari’s book, “Khair-ul-Bayan. Bayazid, the Geoffrey Chaucer of Pashto literature, lived between 1526? and 1574?,

- 26. 26 and influenced not only the literature of Pashto language, in which he composed both prose and poetry, but is also greatly contributed to the Phonetic studies of Pashto, by devising thirteen new alphabets adding them to the set of the existing inventory of Pashto alphabets at that time. Thus he can be called as the first phonetician of the Pashto language. His book was written in the Nastaliq, the Arabic-based script as adapted the writing script of Persian, which itself ‘began to be recognized as an independent form in the second half of the fourteenth century’ (Hanaway & Spooner 1995). It is considered to be a textbook by recent critics and researchers (Haq1986; Guide 1990). It does contain passages about the essentials of Islam, and the message of God the writer wanted to convey to the common masses, which may be understood by ordinary people. Rozi Khan Barki writes about the script of Khair-ul- Bayan that it was composed by the learned author in ‘standard’ Pashto, a dialect which had no legal or official status at that time, but which at least was the dialect which was in vogue for literary compositions, and was not only understandable to all the readers of Pashto but was also the language of formal communication in which religious as well as moral ideas were communicated by learned authors to the masses at large. His belonged to the people of Urmar who was an Urmary or Bargasta speaking tribe (Himayatullah Yaqubi, 2013) but since he was a man of erudition, he knew how important his message was for the masses at large, and that was why he used a dialect of Pashto for his communication which was more prolific and universal so as to spread his message to everyone. He knew that the dialect of his mother tongue, the Waziri Pashto was not understood in the Peshawar valley as the Peshawari dialect

- 27. 27 which was the language of formal communication. Bayazid also knew the fact that it is the Peshawari Pashto in which the literary composition will be made as the reading lot consisted mainly of the ones who read and spoke the Peshawari Pashto. Dr Yar Muhammad Maghmoom also adopts the same stance in describing the linguistic significance of that book and states that the book was composed in a universal dialect which would be spread and read all over the Pukhtoon readers both in Afghanistan and the current Khyber Pukhtunkhwa as well as the Pukhtoons living in the part of the subcontinent to be later called India. Thus he used a dialect, standard for that time, though that was not defined to be standard as such. But its acceptance as a standard dialect was in place. In response to Bayazid’s book, Akhund Darweeza Baba (1533-1619), wrote his own book Makhzan ul Islam. The Makhzan (or treasure) was a rich collection of Arabic religious texts translated in Pashto. Moreover, the language of exposition was Pashto. This book is said to have been taught both in the madrassas and at homes by women to other women and children. It was also read out to those who could not read it themselves. This book was also composed in a dialect easily understandable for the entire community of Pashto speakers, and that dialect was the Peshawari Pashto. Another book which is said to be part of the curricula, especially for women, is Mulla Abdur Rashid‘s Rashid-ul-Bayan. This was written in AH 1124 (1712). Rashid‘s ancestors are said to have come from Multan and he lived at Langarkot. It was read by women in their homes and was a kind of sermon in verse. The following lines from it will serve as illustration of the whole. The nature of the deity, for instance, is described as follows:

- 28. 28 Na e naqs shta pa zat ke/ Na e aeb shta pa sifat ke i.e. Neither has He any defect in His Being nor has He any fault in His qualities. Bayazid Ansari, an influential politician and religious leader of Pathan origin who had lived during the second period of the literary evolution of the linguistic system known today as Pashto, has been known to pride himself to be the creator of the letters of the alphabet which he had developed through the superimposition of Pashto letters over those of Arabic and as a result developing the new alphabet according to oral traditions. Similarly, Khoshal Khan Khattak had devised a new Pashto script after substantial amendments but that could only last up to his family because Mukhzin-ul-Islam which was taken as a text book, and its script obtained popularity and became deep rooted in society during a short span of time, and the same script remained functional with slight modifications until the recent past (Pakhto Lik Laar 1991). The literature of Pashto, as well as its script, has undergone evolutionary changes mainly put into effect by Pathans like Khatak, Darwaiza and Bayazid. The Pashto Academy at Kabul Afghanistan was created for the standardization of the language in Kabul in the early nineteen hundreds, contributed to this very task to research on the influence of foreign languages, more concretely Persian and Arabic which had influenced the writings of the Pashto authors who used the languages as a model for their style and topic selection. Nevertheless, they kept in mind the preservation of the characteristic norms of Pashto.

- 29. 29 A glance at the books of prose and poetry available in the libraries reveals that the poets and prose writers since the 17th Century have been using the same dialect for their literary compositions. Great scholars, intellectuals and poets as well as prose writers of Pashto literature in the entire region have been using the same dialect for their literary compositions. As D. N. Mackenzi puts it, a 'Standard Pashto', in its discreet native dress, as a universal literary medium among Pashtuns, carries a conceptual phonemic system which is reflected in the verses of the great classical poet Khushal Khan Khatak (1613-1689), who was a Khatak by tribe, and whose father was killed by the Yusufzais in a battle, remained a declared enemy of the Yusufzai tribe and had fought several battles with them on behalf of the Mughal emperors. But if we study the literary works of Khushal Khatak, we see that he used the Peshawari dialect for all type of literary composition, poetry or prose. The Peshawari dialect was spoken by the Yusufzais and composed literature in the same dialect, Khushal Khan, despite all his enmity with the Yusufzais, adopted the same dialect for his literary compositions since he knew that it was widely used and understood by Pukhtoons not only in the region but by the Pashto speakers the entire Indian subcontinent. Similarly, Abdur Rahman Baba (1632-1711), who was a Momand by birth, but he used the Peshawari dialect for his poetry and in his entire Diwan (collection of his poems) no single verse could be found in the Momand or other dialect of Pashto. Poets of great repute in the following century also composed poetry in the Peshawari dialect. The famous poet, known by the name ‘hair splitter’ for his glorious imagery, Abdul Hameed Baba (1669-1732), and Ali Khan Baba (1737-

- 30. 30 1766) were Momand by birth but they composed poetry in the Peshawari dialect. Famous Pashto Poets of the modern era also used the Peshawari dialects for their literary composition whether prose or poetry. Famous poet, Fiction writer and Dramatist, Amir Hamza Khan Shinwari (1907-1994) was a Shinwari by tribe. Similarly, Misri Khan Khatir Afridi (1929-1961), known as the John Keats of Pashto for his beautiful imagery and rosy expression in his poetry, was an Afridi by tribe, but no single verse can be found in Shinwari or Afridi dialects in their entire poetry. Famous novelists and dramatist, fiction writer and journalist, Rahat Zakhaeeli (1885-1963), famous poet and literary figure Abdul Akbar Khan (1899-1977), one among the most influential critics and literat, Siyyid Taqweemul Haq Kakakhel (1927-1999), renowned scholar, critic and researcher, Dost Muhammad Kamil (1915-1981), renowned poet, famous by the name ‘the crazy philosopher’, Khan Abdul Ghani Khan (1914-1996), reputed scholar, researcher, critic and poet, Qalandar Momand (1930-2003), revolutionary poet, Ajmal Khatak (1926-2010), a living legend among the poets of Pashto, Rahmat Shah Sayil (1949- ), research and critic, Hameesh Khalil (1930- ), researcher, scholar and a poet of high repute, Dr Salma Shaheen (1958- ), famous critic, scholar, researcher and poet Dr Sahib Shah Sabir (Late), famous poet and dramatist, Dr Muhammad Azam Azam, renowned scholar, researcher and literat, Dr Nasrullah Wazir (Director Pukhto Academy), research fellow at the Pashto Academy, Dr Sher Zaman Seemab, research fellow at Pashto Academy, Dr Noor Muhammad Betani and many other great scholars, researchers, critics, linguists and intellectuals whose names are difficult to

- 31. 31 list here, are few of the many writers who composed literature, both in prose and poetry, in the Peshawari dialect. Another fact which invites our attention is the writings of the foreigners who either composed poetry and prose in Pashto literature or any book of grammar or syntax, they wrote it in the Peshawari dialect. The British knew the significance of Pashto language in dealing successfully with the Pukhtoons. Its importance can be gauged from a report on Pashto language which reveals that, in addition to being spoken in Afghanistan Pashto is also spoken by 1,200,000 people in India. The report states: Pashto is all important as the lingua franca on the Indian North West Frontier. If there is any trouble there, a knowledge of Pashto is indispensable. Its political importance can be gauged from the fact that it is studied in both German and Russian Universities. It is also the language of our Pathan troops (Committee 1909: 117). The learned Englishmen, at least, were supposed to learn Pashto if they wanted to successfully deal with the Pukhtoons in the area called by them the North West Frontier Province. The official orders by the British Government reveal the significance of Pashto for the rulers at that time. One of such orders states as follows: All the Indian Frontier officers and Missionaries in the frontier must know Pashto. These are many in number. At present they have to learn the language on the spot, and some who are good linguists know a good deal about it, but once they leave their duty their accumulated knowledge is lost. The

- 32. 32 arrangements for teaching on the frontier are imperfect (Committee 1909: 117). The arrangements made to teach to such British officers were generally private ones. Englishmen generally hired the locally available private tutors for nominal payments, crammed grammars and lists of certain vital words written by English authors or took lessons from tutors hired by their organizations for the purpose. Among the officers, who were linguists, there were many who wrote grammars and dictionaries. The most well known among these are Captain H.G. Raverty, H.W. Bellew, George Morgenstierne and, George Grierson. Raverty’s dictionary, completed in July 1860, in its preface refers almost entirely to the military, and political, significance of the language. Among other things he said, was an important point to make which is that, the Indian Pathans, or go-betweens of Afghan origin from India, should not be sent to Afghanistan for the purpose of mediating between the Afghans and the government. Rather we must free ourselves from dependence upon them, and that could be done by sending as agents into the country men practically acquainted with the language spoken by the people, or, at least, with the language in general use at the court of the ruler to which they may be accredited’ (Raverty 1860). Raverty also added that the Pashtuns had sided with the British during the upheaval of 1857 and, the Afghans should be enlisted, as well as Sikhs and Gurkhas, into every regiment or, even regiments of each ethnic group may be created. He goes on to say further that another reason was that the Russians, who taught Pashto at St. Petersburgh, would be advantaged by their knowledge of the language whereas the British, who actually

- 33. 33 ruled over the Pashtuns, would not be able to influence them. Raverty argued that schools should be established ‘for the express study of Pashto and the government must make it compulsory for its officers. His own dictionary; textbook called Gulshan-i-Roh; and grammar; he says, are meant to facilitate the learning of this important language. Raverty’s complaint about British indifference to Pashto gained some support from the fact that a German scholar, H. Ewald, rather than an English one, pioneered the study of Pashto. Ewald and other German linguists with interest in Pashto, wrote books of grammar and articles on the sound system and a grammar of Pashto from 1893 onwards. Indeed, as Annemarie Schimmel in her extremely useful study of the German linguists who have studied Pakistani languages puts it, ‘Geiger’s contribution gave the study of Pashto a new, firm ground on which the coming generation could work’ (Schimmel 1981). Such German works provided material for the study of Pashto to British officers. However, since they were meant for linguistic study, they had less specifically pedagogical material than the works of British linguists. The Indian tutors facilitated their British pupils to learn Pashto. Indeed, the very first grammar of Pashto, entitled Riyaz al-mahabba was written by Mahabbat Khan, son of Hafiz Rahmat Khan Rohila, in 1806-7 ‘for a British officer’ (Schimmel 1981). One of the first such books was Tutor to Pushto and it was published in 1896 by Moulvi Ismail Khan as ‘a perfect help to the lower and higher standard Pashto examination’ (Khan 1896). Some of the tutors of Pashto, such as Qazi Najamuddin Khan and Qazi Behram Khan, both father and son, made this practice a family profession. Behram’s son

- 34. 34 Qazi Abdul Khaliq was also an ‘officers language teacher’ in Peshawar and wrote his short booklet Fifty Lessons to Learn Pashto. Moreover, the medium of communication in mass media is also the same dialect which has a wide circulation and recognition and is a source of communication for the Pukhtoons of the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa with the rest of the world. The textbooks, the novels, the drama and other pieces of writing such as essays, treatises and articles are composed in the same dialect. This dialect is also the unofficial medium of instruction in schools and colleges as well as in the Academy of Pashto in the University of Peshawar, though Urdu is the official medium of communication in the government organizations and educational institutions and English is the medium of instruction in the private educational institutions. In my view this dialect is selected by the users of Pashto language due to a number of reasons. Apart from the historical reasons, in my own assessment, most important reason is the metrical and structural simplicity of the Peshawari dialect. Though it is called the ‘hard’ dialect due to the presence of certain phonetic elements, which this book will try to address, if it could, but the overall impression of the Peshawari dialect is that of a smooth and easy to understand dialect. Therefore, the focus of attention for this book is also the Peshawari dialect. As enunciated above, D. N. MacKenzie has rightly pointed out that despite being the most widely used dialect, and despite the fact that literature of international standing has been composed in the Peshawari dialect, it is yet to be recognized as standard dialect. He says, “This literary language has long been referred

- 35. 35 to in the West as 'common' or 'standard' Pashto without, seemingly, any real attempt to define it.” The knowledge of phonetics and phonology of English is necessary for all those who want to know the principles regarding the correct use of English speech sounds. It is important to learn English pronunciation in terms of phonemes rather than letters of the alphabet, because of the confusing nature of English spelling (Peter Roach 2000). The accent that is used as a model for foreign learners is Received Pronunciation (BBC Pronunciation). It is the accent that has been used as the basis for textbooks and pronunciation dictionaries and so is described in more detail than other accents of English (Roach, P 2000) This book is dedicated to the same cause. It focuses on the Peshawari dialect and if its reading could convince the readers as well as the authorities who define and declare a specific dialect of Pashto as the standard dialect, this might well be a successful attempt to prove that it is the Peshawari dialect that is the standard. In the words of MacKenzie, the criteria of dialect differentiation in Pashto are primarily phonological. It is the same reason that this book is designed to address the phonological aspect of the Peshawari dialect. It does not mean that the orthographic aspect is ignored. It rather means that the phonological aspect of the dialect is taken into consideration due to the fact that the other differences of vocabulary and syntax are not so great as to invite immediate attention and a detailed focus. This book is an attempt to describe the phonetical aspect of the Peshawari dialect, a variety of Pashto used since centuries.

- 36. 36 What is a dialect? Hudson (1996, p. 22) defines a variety of language as ‘a set of linguistic items with similar distribution. According to Hudson, this definition also allows us ‘to treat all the languages of some multilingual speaker, or community, as a single variety, since all the linguistic items concerned have a similar social distribution. Ferguson (1972, p. 30) offers another definition of variety: ‘A body of human speech patterns which is sufficiently homogeneous to be analyzed by available techniques of synchronic description and which has a sufficiently large repertory of elements and their arrangements or processes with broad enough semantic scope to function in all formal contexts of communication.’ Note the words ‘sufficiently homogeneous’ in this last quotation. Complete homogeneity is not required; there is always some variation whether we consider a language as a whole, a dialect of that language, the speech of a group within that dialect, or, ultimately, each individual in that group. Such variation is a basic fact of linguistic life. Hudson and Ferguson agree in defining variety in terms of a specific set of ‘linguistic items’ or ‘human speech patterns’ (presumably, sounds, words, grammatical features, etc.) which we can uniquely associate with some external factor (presumably, a geographical area or a social group). Consequently, if we can identify such a unique set of items or patterns for each group in question, it might be possible to say there are such varieties as Standard English, Cockney, lower- class New York City speech, Oxford English, legalese, cocktail party talk, and so on. One important task, then, in

- 37. 37 sociolinguistics is to determine if such unique sets of items or patterns do exist. As we proceed we will encounter certain difficulties, but it is unlikely that we will easily abandon the concept of ‘variety,’ no matter how serious these difficulties prove to be and see whether the description of this dialect can help in understanding the aspects of the other regional dialects of Pashto. From the very outset it is essential for me to make a point clear to the readers that there is a difference between an accent and a dialect. Accent is the way a person or a group of persons speak a specific language. It means that accent is specifically related only to the pronunciation of a language. For example, a speaker of Peshawar pronounces the English word ‘how’ as ‘sanga’ in Pashto. The speakers of Swabi, Swat, Buneer and Dir districts pronounce it as ‘sanga’ while a speaker from district Charsada will pronounce it as ‘Singa’. The pronunciation of the same word differently by different speakers of the same language is said to be an aspect of accent. Accent tells us where a speaker is from. When a speaker starts speaking to us, he speaks our language Pashto but a careful listener automatically understands that the speaker is either from Charsada or Kohat or Peshawar or any other region of the province. What is it that helps us in recognizing a speaker from his very act of speaking a few words? We do not wait to understand the structure of his sentence but get the feeling from few words that the speaker is from this or that district. This is because of his accent. Languages have different accents: they are pronounced differently, people from different geographical place, from different social classes, of different ages and different educational backgrounds (Roach, 2000). Thus accent

- 38. 38 relates only to the way a speaker pronounces certain words. Accent is the way different people pronounce the same language. The difference might be because of the fact that its speakers belong to different geographical regions, social classes and educational backgrounds or different age and gender groups. We will come to this discussion in the later part of the book. Speaking about a dialect is more comprehensive than that. A dialect is a variety or type of language which is not only different in pronunciation but also different in syntax (grammar and sentence structure) and vocabulary and sometimes different in morphology or the order of words. Accent is only one part of a dialect. Other parts are vocabulary, syntax, morphology and word order etc. This book will focus only on the Peshawari dialect and will take into account mainly its pronunciation, and of course some of its vocabulary items to elaborate its phonetical aspect, and to some extent the syntax and morphology for the purpose of elucidating the phonetics and phonology of this dialect. The reason is that it is the Peshawari dialect that appears in print media and newspapers and textbooks. It is the dialect which is heard on the TV and Radio channels in the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province. Pashto is also spoken in the accent of the Southern Districts such as Waziristan, Bannu, DI Khan and Kurram etc. But the Pashto of those districts is different in pronunciation as well as in vocabulary and syntax. Those dialects are to be treated separately in another such book because during a discourse situation sometimes even the speaker of the Peshawari dialect has to ask the speakers of the southern districts to repeat what they said because it is not understandable for him in the first go, particularly when he hears a faster speaker. It is not like the

- 39. 39 southern districts speak different language. They speak the same Pashto. It is because of the difference in vocabulary and pronunciation that sometimes the speakers of one dialect look alien to the speakers of another dialect or accent. After carefully listening they understand each other though. This is not the scope of this book to discuss all the dialects of Pashto. A detailed description of the southern dialects will require another book of such nature which can be composed by a speaker of those dialects. The accent that this book concentrates on and uses as a model is the one that is recommended for the foreign learners of Pashto which can help them understand the TV and Radio news channels in the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa Province, as well as the newspapers and journals published in Pashto around the country. It is also for the native speakers of Pashto who want to learn the language of formal communication and understand what is disseminated in the media. The dialect which this book will describe should be called the Standard Dialect of Pashto i.e. the Peshawari dialect, which would be abbreviated as SDP in the following pages. There is no implication in selection of SDP as a standard dialect that other accents or dialects of Pashto are inferior or less standard. It is only for the purpose of making the job of Pashto language teachers easier who want to teach Pashto language either to foreign learners of Pashto or the natives speakers of Pashto at school, college or university level. It is supposed to make the job of those foreign learners of Pashto easier who want to have some knowledge of the Pashto language, even without the help of a teacher. For those readers of this book, who are the native speakers of Pashto, it is not mandatory to change their pronunciation patterns after having

- 40. 40 gone through the book. I do not ask the native speakers to change their own way of speaking their native tongue after reading this book. It is, of course, suggested for the native speakers of Pashto, to read the book and concentrate on SDP, which over the course of reading this book, they will find it interesting to know that they can identify the ways in which their own dialect is different or similar to the SDP and how can they judge whether their dialect is close to the SDP or otherwise. The readers can even learn to pronounce utterances of accents other than their own and that will benefit them in their knowledge of the dialects of their native tongue. The Pukhtoons have always been a very important nation for those who aspired to influence the western part of the subcontinent in olden times. From the time of the Guptas down to the Greek Alexander and in the 19th century to the British, this region where the Pukhtoons have resided for thousands of years has been a focus of attention for many rulers and invaders. The Pukhtoons have kept their traditions intact during several centuries. They consider themselves born warriors and never let any ruler rule them unless the invader has come to good terms with them. One way of winning the Pukhtoons is by behaving good towards them. Leaning their language and interacting with them is yet another trick to subdue this nation. It is somehow a general rule of thumb to avoid enmity of a nation by learning its language. If interaction with the Pukhtoons is needed, one must learn their language because of many reasons, the first and foremost being that most of the Pukhtoons lack exposure to foreign language and cultures. The British had adopted a policy for the Pukhtoons to keep them deliberately away from

- 41. 41 education, and thus had closed one big gateway for them to achieve progress and economic prosperity. Keeping in view the competitive and economic age of today, the significance of any language cannot be underestimated. Particularly, in a region like the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province where a global economic activity in the form of China Pak Economic Corridor is proposed to be launched, the regional language of the province is of supreme importance for all investors in the project, particularly China, in that the jobs and employment opportunities are to be availed by the residents of the Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province. The Chinese or other investors cannot afford to bring their own staff from the top level to the bottom, and thus some of the employments slots have to be filled by the regional residents, no matter higher or lower in ranks, who will have to interact with the foreigners, be it Chinese, Saudis or other investors. It is believed that the CPEC project will open new avenues of growth and progress which will result in regional prosperity for the country. In this regard, the residents’ multilingual skills will go a long way in tapping the maximum benefits towards attaining the goal of a sustainable economic development. In order to make CPEC a success, bridging the language and cultural gap between the regional and the global stakeholders is of supreme importance, besides catering to the investment and profit needs of the investors. The Pakistani scholars, in matters of finance and linguistics, have to play a vital role in coming up to the expectations of the two countries in order to make CPEC a true success for the country as well as for the region. Pakistanis need to learn Chinese language, and culture and reciprocally the Chinese and other stakeholders of CPEC need

- 42. 42 to learn about Pakistani culture, as well as the regional languages, in order to break the linguistic barriers to realize the full potential of the CPEC project. It is with such a crucial purpose in mind that this research work was conceived for providing a platform both to the native and non-native learners of Pashto, not only with CPEC in mind, but the interest of global powers in the region ever since the start of the cold war. For thousands of years this region, the Peshawar valley, has been a center of attraction for rulers, investors and religious missionaries. Only the British realized for the first time that along with political and financial knowledge of this region, a more in depth cultural and linguistic understanding was also needed if the Pukhtoons have to be handled in a shrewd way. The bilateral relations between Pakistan and China are excellent since the independence of Pakistan, but unfortunately people of both the countries have less awareness about each other’s culture and languages. After CPEC, China and Pakistan both need to have an in depth understanding of each others’ culture and language because it is understanding of such values which goes a long way in bilateral relations, apart from the use of money and power between two countries. The purpose of this book is two-fold. In the first place it intends to describe the vowels and consonants of Pashto to elucidate it by putting it in comparison with vowels and consonants of English, which is an international language, and will help every leaner of Pashto who aims to master the phonology of Pashto and that will sound more easy if the base for understanding Pashto phonology is the phonological system

- 43. 43 of English which is known worldwide. Secondly, this research work intends to propose a theoretical framework for the study of Pashto language, particularly the Peshawari dialect, since it is the dialect that appears in the print and electronic media. Learners, particularly the non native learners of Pashto, and to some extent the natives learners of Pashto have difficulty in the pronunciation of certain phonemes and phonological patterns, which they needed to comprehend in order to easily understand Pashto and its literature. As for the users of Pashto language at an advanced level, say, at research or Teaching of Pashto as a native tongue or Teaching of Pashto as a foreign language level, this book is hoped to be of help to such users in that it will provide to them a theoretical framework in understanding the principles regulating the description and use of sounds in Pashto language. The general readers of this book will also receive help in identifying and differentiating the vowel and consonant sounds of Pashto for a deeper understanding of the sound patterns which are similar or different between Pashto and English. Keeping in view the number of speech sounds in Pashto language, it might be theorized that the native speakers of Pashto are at an advantage to master the sound system of any language in the world, as the range of speech sounds covered in Pashto is vast. Last but not the least, the standard for pronunciation in this book will be the one prescribed by the International Phonetic Alphabet. Over the course of reading, the readers will compare the speech sounds of Pashto with the standard speech sounds given in the IPA chart, which has been utilized by Peter Roach for his description of the English vowels and consonants. We will see whether a vowel or consonant of Pashto matches

- 44. 44 the vowels or consonants in the IPA or deviate from them. In case of deviation, what is the level and degree of deviation and to what extent is the English Language helpful in identifying such sounds and how to resolve the problem faced by learners of Pashto. It is worth mentioning that the speech sounds of Pashto are not supposed to follow the set pattern of the speech sounds in IPA chart. We will bring the comparison in our discussion for the sake of the convenience of the learners of Pashto as the IPA is an international standard which can be followed by learners of any language worldwide. The IPA charts for the vowels and consonants are given on the next page.

- 45. 45

- 46. 46 Chapter 2 The Phoneme, phonetics and phonology The Phoneme The word phoneme has been derived from the Greek word ‘phone’ which means ‘a sound’. Phoneme is defined as, ‘any of the perceptually distinct units of sound in a specified language that distinguish one word from another, for example p, b, d in English language. The Oxford Dictionary defines a phoneme as, ‘Any of the perceptually distinct units of sound in a specified language that distinguish one word from another, for example p, b, d, and t in the English words pad, pat, bad, and bat.’ In Pashto phonetics and phonology, the same definition is to be utilized for explanation. Consider, for example the words ‘’کټ i.e. ‘bed’ and ‘ بند ’ i.e. ‘closed’. The first word contains /k/ and /t/ consonants which are called phonemes. The /a/ in the middle of ‘’کټ is a vowel which is also a phoneme. Similarly, in the word ‘bund’, the phonemes are /b/, /u/, /n/ and /d/. Phoneme is the minimal distinctive unit of sound, whether a consonant or a vowel, which cannot be further divided into smaller parts. It means that a phoneme is that unit of sound which cannot be simplified. The term ‘distinctive’ is also important to understand. Distinctive means ‘unique’. It means a sound which cannot be replaced. If it is replaced by any other sound, it will change the meaning of the word totally. For example, if we replace the /k/ in the word ‘kat’ by a phoneme /s/, the word will become ‘sat’ and it means different than the word ‘kat’. Thus both the /k/ and /s/ are distinctive phonemes of Pashto and if we replace them in words with different phonemes, the meaning of the word will be totally changed. A

- 47. 47 phoneme is not a letter or alphabet. There can be alphabets which might contain a number of phonemes. For example the alphabet /./ﺝ If we pronounce the alphabet as ‘jeem’ it will contain three phonemes namely, /j/, /e/, /m/. The first is a consonant while the second is a vowel which is pronounced as a long vowel equal to the length of two e vowels but we will come to the length of vowel in the chapter that deals vowels. The phoneme /j/ will also be discussed at length in the chapter which deals with consonants. Allophone At this stage it will complicate things too much but I suppose it is important for readers to understand another concept related to phoneme which is ‘allophone’. The Oxford Dictionary defines an allophone as, ‘Any of the various phonetic realizations of a phoneme in a language, which do not contribute to distinctions of meaning. For example, in English an aspirated p (as in pin) and unaspirated p (as in spin) are allophones of /p/. Aspiration here means the release of a puff of air while pronouncing certain phonemes. For example in Pashto the word ‘pat’ i.e. ‘hidden’ can be pronounced without aspiration as /pat/ and the ‘p’ can be pronounced with aspiration as /phat/. Here it is worth noting that the aspiration does not change the meaning of the word. Only a specific feature of pronunciation is added to the phoneme /p/ i.e. aspiration. If we replace the /p/ by any other phoneme e.g. /s/ then the word becomes /sat/ and its meaning will be changed. It means that an allophone is not a different phoneme. It is in fact the same phoneme but some feature of pronunciation is added to it. Or we may say that its realization becomes slightly different because of some feature of pronunciation such as aspiration. Aspiration depends on the

- 48. 48 choice of the speakers. It may also depend on the accent one uses. Some accents have more aspirations while others may have lesser aspiration. Particularly in literary speeches, such as narration of poetry or a treatise, the speaker may choose to use more aspirated words to create special effects for impressing the audience. For example the simple word, /sta/ i.e. ‘your’ or ‘yours’ might be pronounced as /stha/ for creating a more poetic impression on the audience. Similarly, words likes /starry/ i.e. ‘tired’, might be pronounced as /stharray/ by the speaker to let the audience realize the very meaning of tiredness. There are other phonetic features such as stress and intonation in Pashto, which are called supra-segmental features of phonology, the detail description of which will be made in the relevant chapter. After having cleared our concept of phoneme and allophone, we can now afford to move forward and step into the discussion of phonetics. Phonetics and Phonology Many readers of language and linguistics take phonetics and phonology to be synonymous. After spending some time with the study of language, the difference between the two terms gets clearer and clearer but it is only the matter of time and attention. Let us define phonetics separately and then we will discuss its relation to phonology. Phonetics The Encyclopedia Britannica defines Phonetics as, it the study of speech sounds and their physiological production and acoustic qualities. Acoustic means something relating to sound or the sense of hearing. Britannica further goes on to say that

- 49. 49 the study of the anatomy, physiology, neurology, and acoustics of speaking is called phonetics. The scope of this definition is much wider and much more comprehensive. To the extent of this book, we can rely on understanding phonetics in simple words that phonetics studies the physical characteristics of speech sounds that are uttered by human beings for making speech utterances. It takes into account where and how the speech sounds are produced in the oral or nasal cavity and any other place of articulation involved in the production of speech sounds. This also includes the study of the air stream produced in the diaphragm and the vocal box which produces an air stream that helps in creating the speech sounds in the oral or nasal cavity. The speech of human beings is more complex than it apparently looks. A number of different studies are involved only in the sound aspect of human speech. It requires the help of various scientific apparatus to observe and bring under experiment if we want to explain its various aspects. For this purpose various branches of phonetics have been identified in which separate aspects of human speech are studied. The branch of phonetics that deals with the configurations of the vocal tract used to produce speech sounds is called articulatory phonetics. Similarly, the study of the acoustic properties of speech sounds is known as acoustic phonetics, and the manner of combining sounds so as to make syllables, words, and sentences is linguistic phonetics. Yet another branch of phonetics that deals with the study of the medium of the speech sound, is called auditory phonetics. We will limit the scope of our study of phonetics only to articulatory phonetics due to the fact that our concern here in this book is with the study of the physical

- 50. 50 characteristics and articulation of the speech sounds of Pashto language. Through articulatory phonetics we will try to identify the number of speech sounds in Pashto language and their manner and place of articulation. We will also attempt to differentiate between the consonants and vowels of the Pashto language, in the context of the Peshawari dialect specifically. The standard, against which this book will attempt to describe the phonetics and phonology of the Peshawari dialect of Pashto language, is the International Phonetic Alphabet which has been designed by the International Phonetics Association. International Phonetic Alphabet International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), is a set of alphabet developed in the 19th century to accurately represent the pronunciation of languages. The International Phonetic Association is responsible for the alphabet and publishes a chart summarizing it. One aim of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) was to provide a unique symbol for each distinctive sound in a language—that is, every sound, or phoneme, that serves to distinguish one word from another. The concept of the IPA was first broached by Otto Jespersen in a letter to Paul Passy of the International Phonetic Association and was developed by A.J. Ellis, Henry Sweet, Daniel Jones, and Passy in the late 19th century. Its creators’ intent was to standardize the representation of spoken language, thereby sidestepping the confusion caused by the inconsistent conventional spellings used in every language. The IPA was also intended to supersede the existing multitude of individual transcription systems. It was first published in 1888 and was revised several times in the 20th and 21st centuries.