Ogoni Oil: Economic and Political Underrepresentation, and Environmental Degradation

- 1. 1 Ogoni Oil: Economic and Political Underrepresentation, and Environmental Degradation Centre for Environment, Human Rights and Development, 2014

- 2. 2 Title Page SPRING 2015 GLOBAL STUDIES CAPSTONE SEMINAR SONOMA STATE UNIVERSITY TITLE OF REPORT Ogoni Oil: Economic and Political Underrepresentation, and Environmental Degradation GROUP The Underrepresented Ones HAND-IN DATE April 30th, 2015 SUPERVISOR Rheyna Laney and Jeff Baldwin TOTAL NORMAL PAGES 57.45 pages (137,888 characters with spaces) Rebekah Cryderman ________________ Lauren Silveira ________________ Jackson Stogner ________________ Taylor Vitangeli ________________

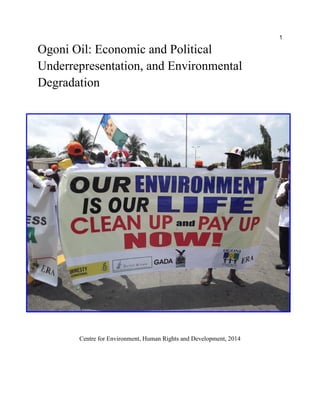

- 3. 3 Acknowledgments and Dedication Our research team is grateful for the opportunity to learn from our peers and our professors at Sonoma State University throughout our academic career. We would like to take the time to thank our Senior Capstone Thesis advisors: John Nardine, Dr. Jeff Baldwin, and Dr. Rheyna Laney. We would also like to express our appreciation to the authors from whom we have used throughout our research to gain extensive knowledge on the topics of the resource curse, corruption, political ecology, environmental degradation, and social movements. Lastly, we would like to vocalize our gratitude and reverence to the local communities of the Niger Delta who continue to strive for their improved well-being despite structural hindrances. Cover photo of a protest by the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) in River State in 2014. Photo courtesy of the Centre for Environment, Human Rights and Development (http://cehrd.com/our-environment-is-our-life-clean-up-and-pay-up-now/).

- 4. 4 Abstract Nigeria’s government, through corrupt practices, has excluded, politically and economically, many ethnic communities in the Niger Delta. These same corrupt practices that have resulted in the underrepresentation of local communities have also caused the marginalization and neglect of the local environment. This neglect of the local environment has further marginalized the local people who rely on the environment as a way of life. The Ogoni community of the Niger Delta serves as a case study for this all-too-common path of developing regions of the world that concentrate on resource extraction. They also represent a community that is mobilizing to address these concerns, and though significant strides at the federal level are yet to be made, there continues to be advocacy for progress on economic, political, and environmental issues. The global context of resource extraction allows the broad themes and salient patterns found through this research to become applicable for further research on other communities, and their social movements, across the globe. Key Words: Niger Delta, Underrepresentation, Social Movements, Oil, Resource Curse, Corruption, Political Ecology.

- 5. 5 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methodology and Research Design 2.1 Approaches 2.2 Case Boundaries 2.3 Frameworks 2.4 Key Terms 3. Literature Review 3.1 The Resource Curse 3.2 Corruption 3.3 Political Ecology 3.4 Local People of the Niger Delta and Oil 3.5 Oil Industry and the Environment 4. Case Study 4.1 Petrol and Layered Logistics 4.2 Impaired Institutions 4.3 Facts about The Ogoni 4.4 The Economic Context of Development 4.5 The Story of Shell Oil 4.6 Environmental Degradation 4.6.1 Environmental Degradation 4.6.2 Environmental Regulations 4.7 Forms of Representation in the Delta 4.7.1 MOSOP 4.7.2 MEND 4.7.3 Local NGOs and Civil Organizations 4.7.4 Regional NGOs 5. Analysis 5.1 The Resource Curse 5.2 Corruption 5.2.1 The Role of Shell Oil

- 6. 6 5.3 Political Ecology 6. Conclusion 7. Perspectives

- 7. 7 Abbreviations AGRA: The Associated Gas Re-injection Act 1979 ANEEJ: African Network for Environment and Economic Justice DPR: Department of Petroleum Resources EEFC: [Nigerian] Economic and Financial Crimes Commission GDP: Gross Domestic Product IRIN: Integrated regional Information Networks MEND: Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta MNEs: multinational enterprises MOCs: multinational oil companies MOSOP: Movement for the Survival of he Ogoni People NDDC: Niger Delta Development Commission NEITI: Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative NER: Nigeria Economic Report NGO: Non- Governmental Organization NNOC: Nigerian National Oil Corporation NNPC: Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation OEL: Oil Exploration License OGEPA: Ogoni Environmental Protection Agency OML: Oil Mining Lease OPEC: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries OPL: Oil Prospecting License PPT: Petroleum Profit Tax PSCs: Production Sharing Contracts PWYP: Pay What You Publish RMAFC: Revenue Mobilization Allocation and Fiscal Commission RSSDP: Rivers State Sustainable Development Program SPDC: Shell Petroleum Development Company TNOCs: Transnational oil companies TPH: Total petroleum hydrocarbon UN: United Nation

- 8. 8 UNEP: United Nations Environment Program UNPO: Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization BBC 2015

- 9. 9 UNEP 2011

- 10. 10 Ogoni Oil: Economic and Political Underrepresentation, and Environmental Degradation 1. Introduction The topic of minority underrepresentation and its potential effects upon the environment arose through a classroom brainstorming session dedicated to drawing out the different focuses our Global Studies major. We then synthesized multiple ideas into a single topic in order to reveal a new path of exploration for our research project. With our concentrations differing between Social, Political and Economic Development and Global Environmental Policy, we realized the potential in covering a topic that allows us all to delve into each of these realms. The interdisciplinary nature of Global Studies allows us to come into contact with similar issues of resource extraction and indigenous empowerment in developing areas of the world, expanding our case study options. Each of our group members has had some exposure to this topic through a variety of courses such as World Regions in a Global Context and Liberation Ecologies. To further focus our topic on a specific region and situation, we discussed options at length involving nearly every continent. After a period of meditation on the exact circumstance to write about, we decided on the oil extraction industry of Nigeria and its local community members who are not involved with, or benefiting from, those processes. This option appeals to our group because of personal commitments to social justice, current reports of Nigeria in international media regarding instability, and our own observations of falling oil prices while understanding from scholastic backgrounds that International Political Economy is what is at play. As a group, we have discussed several key topics that are generally known about underrepresentation and oil in Nigeria. Nigeria is a major oil producing country and a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).1 Despite the vast oil wealth in Nigeria, there is great economic inequality due to inequitable resource allocation.2 The lack of just resource allocation has led to the underrepresentation of many groups within oil producing communities, and has impacted their political and socioeconomic well-being. We also know that 1 Chris Nwachukwu Okeke. 2008. “The Second Scramble for Africa's Oil and Mineral Resources: Blessing or Curse?” .International Lawyer. 42, no. 1. p. 200. 2 Chris Nwachukwu Okeke. ibid., p. 199.

- 11. 11 the Nigerian government has been accused of corruption. Another generally known fact is that Nigeria was once colonized by Great Britain up until their independence in 1960.3 We have made one main assumption throughout our research of this topic: oil production is, in itself, degrading to the environment. With that said, we will explain in more detail the damage that is done by oil spills and gas flaring.4 However, we believe that the detailed discussion of the harm caused by carbon emissions on a global scale is better left to the plethora of existing literature specifically on that topic. At this juncture, we believe that this is the extent of our assumptions. We have recognized that the other ideas that we thought we might be assuming are actually going to be addressed in our research as we move forward. In the areas that have great economic gains to be garnered from mineral or resource mining, there are many dimensions to explore. There is often an associated favoritism of certain shareholders and a neglected interest of undervalued stakeholders in these situations, typically a socio-economic, ethnic, or political minority who goes unheard or unheeded. The political systems in place have embedded social relations into their structures, sometimes referred to as Godfatherism5 , which enables a politician to be chosen based on their strategic alliances and promises to those who have helped them gain the position.6 It is the neglected groups which require mobilization as civil society in order to have their interests advocated for, and which must make sustained efforts to effectively partake in that processes of the planning and extraction.7 Although some progress has been made, the detrimental environmental and social effects of mining endeavors are partly due to the inability of communities to act as partners in these projects and have their wisdom, interests, or input embodied.8 The relation between this disregard and environmental degradation is what our group is hoping to explore through our capstone research project. Our main research question is as follows: "In a country whose economy has relied heavily on mineral resource extraction, how is the political and 3 Jesse Salah Ovadia. 2013. The Nigerian 'One Percent' and the Management of National Oil Wealth Through Nigerian Content. Science & Society. 77, no. 3: 47-75. 4 C.O. Opukri, and Ibaba S. Ibaba. 2008. "Oil induced environmental degradation and internal population displacement in the Nigeria’s Niger Delta’." Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 10, no. 1: 173-193. 5 Okoye, I. 2007. "Political Godfatherism, Electoral Politics and Governance in Nigeria." In Annual Conference of the Mpsa Held In Chicago, USA. p. 3 6 Sarah Chayes. 2015. Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security. WW Norton & Company: pp.125-126 7 Julia Maxted. 2006. Exploitation of Energy Resources in Africa and the Consequences for Minority Rights. Journal of Developing Societies. 22, no. 1. p. 35. 8 Julia Maxted. ibid.

- 12. 12 economic underrepresentation of local communities related to the presence of environmental problems in the Niger Delta?" In addition to the main research question and in order to comprehensively explore the topic, other questions must be asked and researched. These questions include: How has corruption in the government and unequal resource allocation contributed to underrepresentation of local communities in the Niger Delta? How has the theft of crude oil impacted the environment in the Niger Delta? What role does development, or lack there of, play in the economy and underrepresentation in Nigeria? How does the environmental degradation of the Niger Delta affect local populations? How do local politics and social movements in the Niger Delta affect oil extraction in the region? How can the government encourage or discourage the oil industry? The purpose of our research is to explore these connections in a thorough manner and obtain a greater understanding of the current circumstances in the Niger Delta. Our research has the possibility of shedding light upon the crucial environmental leveraging points in the region, across the continent and in other parts of the globe subjected to similar situations. We have the opportunity to impact how others, in academic circles and in less formal arenas, may see both underrepresentation and environmental issues in local and in global scopes. By providing an inclusive contextual framework and a complementary perspective for viewing these themes, we hope to be able to breakthrough the biases surrounding the African continent in popular discourse and create a platform for future research, individual learning, and organizational action to build upon. 2. Methodology and Research Design In this section, we will discuss the approaches we chose in answering our research question. We will also explain the process by which we chose our case study. The case we have chosen is a single instrumental case9 –we can look at this case and use it as an example of a larger problem plaguing many developing countries. The issue of the resource curse, environmental degradation, and corruption are all issues that are by no means confined to the Niger Delta. For this very reason, we have not classified this as an intrinsic case10 –we deem it not to be unique to 9 John W. Creswell. 2013. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage. p. 99 10 Creswell ibid., p. 100

- 13. 13 the region. However, an in-depth look at the situation in the Niger Delta could potentially be generalizable to the greater issues of the resource curse, environmental degradation, and corruption in other states around the world. We have elected to narrow our research to a single case study as opposed to to a multiple case study.11 Due to time constraints, our aim is to fully understand the situation in a single case, rather than weaken our investigation through the task of examining multiple cases with comparable depth. However, in a different setting, a multiple case study could illuminate similarities between cases and provide additional data for future research. A single case study will provide a substantial example to illustrate the multifarious character of our approach and to produce solid findings that lend themselves as pattern-building for other works. The case of the Ogoni people in the Niger Delta can be classified as what Alan Bryman would call an exemplifying case–it demonstrates the circumstances of a situation prevalent around the world.12 This classification also makes a justification for the implementation of a single-case study. We are approaching this study by applying a holistic analysis, rather than an embedded analysis,13 because there will not be a focus on a particular subunit within this case. Rather, we will be examining this case entire case in a more general way. We will be using complex reasoning for our research, applying inductive reasoning to reach conclusions about information gathered, as well as using deductive reasoning to construct themes and compare them with data collected.14 As Creswell suggests, we will be using multiple methods for our research.15 Forms of data will include secondary sources such as books and peer reviewed articles, as well as reliable sources from news outlets. By using multiple sources, we can triangulate evidence and remove any inconsistencies presented in single-source data. The validity of these document sources have been investigated by our group through the critical examination of primary sources for first-hand account evidence, and secondary sources to reiterate main points we make, and find differing points of view. Tertiary sources will only be used to remain up to date on current activities occurring in the Niger Delta.16 We have been 11 Creswell ibid., p. 99 12 Alan Bryman. 2008. Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press. p. 56 13 Creswell op. cit., pp. 100-101 14 Creswell ibid., p. 45 15 Creswell ibid. 16 Kate L. Turabian. 2013. A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. University of Chicago Press. pp. 25-27

- 14. 14 adamant to use the works of respected field experts, university-affiliated professors, reliable local organizations, and other credible authors who are part of reputable publishers and institutions. 2.1 Approaches We are using an emergent design for this research paper; in other words, as we accrue information and gather an increasing understanding of the topic, our research plan will evolve accordingly.17 Our intent is to produce a paper that is credible, transferable, dependable and confirmable.18 To ensure a final work that has internal validity, our explanation of the causal effects will show a strong relationship between the independent variable of government activity and the dependent variables of environmental degradation and underrepresention.19 External validity will be established through our global framework which reflects upon the greater application of findings from this common case, and ecological validity will be addressed through the localized analysis of how indigenous groups are affected daily by the reality of their situation.20 Constructing comprehensive qualitative research requires an awareness of researcher roles in interpretation and the involvement of natural viewpoints which are “sensitive” to the subjects being considered.21 A quantitative approach is unable to capture the intricacies of people on the ground who are experiencing their lives within such a living, breathing context. Our data is no less credible than numbers and because our focus is on the well being of humanity, the situation may provide a more suitable occasion for analysis using epistemologies like social constructivism rather than more rigid or reductionist methods like postpositivism.22 The interpretivism embodied in our research is a logic utilized to seek an understanding of the experience for marginalized communities rather than only looking for confined explanations of the situation in the Niger Delta removed from human ascription. The subjects of our analysis are essential to the hermeneutic approach we plan to employ; the hermeneutic approach recognizes the significance of individual thought and processes that may impact a situation or environment.23 Through the interpretation of data from the perspective of participants, we 17 Creswell op. cit., p. 47 18 Bryman. op. cit.,. p. 34 19 Bryman ibid., p. 32 20 Bryman ibid., p. 33 21 Creswell. op. cit., p. 44 22 Creswell. ibid., p. 24 23 Bryman. op. cit., p. 15

- 15. 15 acknowledge that our subjectivity may be a source of analysis but we will actively make it a point to convey the meanings of our research by people actually living the experiences we describe. Upon a group reflection, we have discovered several predispositions engendered by our academic and social experience which may lead to a perspective on the topic that differs from those of other researchers. One major potential partiality is our feelings about the prospect of oil; we all agree that the production of oil is a dead end road that should not gather continuing investments in the future. For this reason, our perspective on oil production, and thus, the issue of environmental degradation as a result of said production, may inherently be perceived as negative. The other main potential bias which might be found in our research paper is that we are all partial to local perspectives over foreign or corporate perspectives. For this reason, our perception of conflicts between the two may lean towards favorable outcomes for local communities. Our feelings on these topics stem primarily from our academic background. The lifeblood of the Global Studies major is the desire for the understanding of global issues. Three of our members have a concentration in global environmental policy. Thus, environmental degradation is a sensitive subject. The fourth member of our group has a concentration on social, political, and economic development of developing nations, so naturally, conflicts between local communities and outside forces are of particular concern. These are the two main biases among our group. With that said, we will apply a holistic account24 –we will make it a priority to acknowledge and address the various perspectives in this complex case in order to help us understand the situation as a whole. These ethical leanings are situated within a research format which applies a constructivist approach, meaning that we recognize how the significance and understanding of situations are socially constructed by individuals as well as researchers, and we have left our questions intentionally open in order to receive a more varied response from all angles.25 We will analyze the relevance of theories that build our framework as well as those that disagree with it in order to cultivate an objective outlook. The avenues mentioned will elucidate 24 Creswell. op. cit., p. 47 25 Creswell. ibid., p.24

- 16. 16 the exploration of our case with multiple perspectives without shaping our understanding in a narrow direction colored by purely personal views.26 2.2 Case Boundaries The boundaries of our study manifest in different levels according to our specific research concentrations: social, environmental, economic, and political. The social dimensions of our study will refer to the Ogoni ethnic group, local activists and other stakeholders living within the Niger Delta in Nigeria. Because of the nature of interstate networks and connections, we cannot confine our research of the Ogoni to a solitary spatial zone, despite the existence of an area designated as Ogoniland. Instead, we have chosen to stipulate our social realm as the entire Niger Delta, a relatively small, 70,000 km²27 portion of the state of Nigeria located where the mouth of the Niger River meets the Atlantic Ocean. The environmental element of our research will arrange itself within the region of the Niger Delta and its surrounding bodies of water affected by Niger Delta oil activity. Our choice to limit the environmental aspects in this manner allows for our work to spotlight the problems incurred by oil extraction, and not other industries, and the difficulties endured by oil producing communities, not other localities which may have a smaller impact from resource extraction practices. To the extent possible, we will attempt to focus our research on the Niger Delta explicitly to provide an unambiguous insight into the current situation. This being noted, we also recognize that the range of economic and political circumstances in the Delta is greatly impacted by the actions of the national government. Hence, for these intertwining yet separate realms of analysis, economy and politics, we will widen our scope to the federal level and delineate our restrictions to the conduct of the Nigerian government, institutions and markets. In regards to temporal limitations, the scope of the case study will be limited to the last twenty years–the time following Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death. We will look at changes and developments in the political and economic status of the Ogoni people from 1996 onward, while comparing it to changes in environmental degradation in the area over the same time period. The focus, though, will be more on recent years than in the few years immediately following Saro- Wiwa’s death. This paper will reference the history of oil in Nigeria, starting at its discovery in 26 Creswell. ibid., p. 60 27 World Wildlife Foundation. 2015. Niger River Delta.

- 17. 17 1956, to encompass the full connotation of what has occurred over time. We feel it is important to look at the past in order to understand the present situation in the Niger Delta. The colonial context and continuous accounts of exploitation provide a more nuanced discernment of current conditions, and demonstrate why communities have felt the need to organize against oil extraction as their needs have been relentlessly ignored.28 This historical information will be used exclusively for the purpose of providing background. We have placed these spatial and temporal limitations for our case study, but we will relate our findings to their significance in a global setting in our paper. Our decision to research this topic was driven by our curiosity to delve into one of the most highly politicized commodities of the global market: oil. Industrialized nations consume this nonrenewable resource at a rapid rate, wars have been fought, and local people conveniently forgotten in order to procure this commodity.29 We have collectively chosen to explore the ongoing struggle for environmental, social, and economic justice in the face of transnational oil corporations and corrupt governments in the Niger Delta through the example of the Ogoni people. Our decision stems from the immense level of activity that has occurred in Ogoniland for decades and the inspiration that has come from learning about the tragedy surrounding Ken Saro- Wiwa and the execution of the Ogoni Nine which gained global infamy in 1995.30 This ethnic group has become a focal point within the Niger Delta and a representation of what can go awry when local peoples endeavor to achieve equality within an unequal system. The Ogoni people have remained active in the Niger Delta as they continue to demand agency regarding their lands and livelihoods.31 2.3 Frameworks For the qualitative research indicative of social sciences like Global Studies, the perspective of the various participants are essential to include and strengthen the work’s worth in the wider world.32 In the instance of our specific research case the topic in question is the underrepresentation of local groups in the Niger Delta and so the largest mistake we could make 28 Maxted. op. cit., p. 33. 29 Julia Maxted. ibid., p. 29. 30 Human Rights Watch. 1996. Nigeria Permanent Transition 1996. 31 Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People. 2015. 32 Creswell op. cit., p. 47

- 18. 18 would be to leave out the voices we have found that need to be heard. Because we have not had the opportunity to travel to Nigeria and observe these circumstances first-hand, we cannot speak from a place of understanding in the way indigenous people of the area are able to. The meaning given and interpretations ascribed to the occurrences in the Delta are most significant when they are provided by those participating in the struggle and advocacy discussed. Stakeholders in the extraction of natural resources in the Niger Delta are multi-level and include: both local and national governments and politicians, state judiciary structures, transnational oil corporations, international bodies, non-governmental organizations, state civil society, and local communities of the Niger Delta that include individuals such as activists, militants, and agrarians. Each contributor plays a significant role in either the perpetuation or prevention of harmful systems. As parties with different concerns, they do not always agree on strategies or even goals. Some citizens have been assimilated into the current markets in a sustainable way but some communities have also been taken advantage of and had to defend their rights to land, livelihood and life from the encroachment of multinational corporations, government mandates and interests that do not represent them. Our research has been guided under a series of related frameworks such as political ecology33 and the resource curse.34 Political ecology is a complex term, the meaning of which we have gathered from Garry Peterson. Peterson defines political ecology as “combining the concerns of ecology and political economy that together represent an ever-changing dynamic tension between ecological and human change, and between diverse groups within society at scales from the local individual to the Earth as a whole.”35 This framework will provide a path of multidimensional understanding as it relates to our study and the heavy leverage that politics have upon an environment. The resource curse which has been outlined by Michael Ross will be an important aspect of our analysis as we explore how the economic climate of the Niger Delta can impact the political circumstances in local communities.36 The resource curse can be described as an instance in which states who have incredible wealth in the form of natural resources are adversely affected by this plenty through a subsequent narrowed focus of policies, 33 Garry Peterson. 2000. "Political Ecology and Ecological Resilience:: An Integration of Human and Ecological Dynamics." Ecological Economics 35, no. 3: 323-336. 34 Michael L. Ross. 1999. "The Political Economy of the Resource Curse." World politics 51, no. 02. p. 298. 35 Peterson. op. cit. 36 Ross. op. cit.

- 19. 19 resulting in nonreciprocal economic remunerations and therefore a slower route to sustainable development. The framework of the resource curse is useful for our research because of its direct relation to the circumstances of extraction-concentrated economies in a developing country like Nigeria. It is also useful for the illustration of the consequences borne by oil producing communities who do not receive equitable compensation for their land productivity and who instead bear political, social, and environmental costs. 2.4 Key Terms There are several key terms that we wish to define, as they will appear frequently throughout this paper. The first key term is corruption. It is a common word, but a clear description of how we interpret it will be beneficial. By corruption, normally referring to government corruption, we mean the illegal and intentionally secret behavior that leads to personal gain at the cost of society as a whole, often in terms of public revenues. Kleptocracy is synonymous with our working definition of corruption, and is a term that may be used throughout the paper to refer to this phenomenon. The next key term is environmental degradation. By this we mean anthropogenic damage to air, land, water, and the ecosystems that benefit from them. Another key term is underrepresentation. In this context, underrepresentation means the lack of a proportional contribution to decision-making regarding social, political, economic and environmental matters. A word we will use synonymously with underrepresentation is exclusion. We are using these words with intent, and define them in a specific fashion, because these concepts are the essence of our research and will arise frequently throughout this paper. They are the most indispensable terms in our study, and it is important for the reader to be able to clearly understand our meaning of these terms as our study unfolds. 3. Literature Review 3.1.The Resource Curse Our two frameworks, political ecology and the resource curse, have guided us in our exploration of applicable literature. We will be able to explore a variety of works by experts in these fields, along with different perspectives concerning the circumstances which the country of

- 20. 20 Nigeria is facing, in order to enhance our understanding and capacity to critically assess those circumstances properly. Chris Nwachukwu Okeke, an accomplished Nigerian professor who has been the dean of two Faculties of Law at Nigerian institutions, calls the present day foreign presence in Africa the “Second Scramble”, a reference equating the colonial era of infiltration and imperialism of African lands to the “modern oil craze” of Western countries and corporations.37 The association of these two time periods has the suggestion of immense exploitation, though the second round has the central difference of increased private sector and international financial institution involvement. Also, compared to the first round which was comprised of mainly government action, the clamber is grasping for not only physical minerals but the control of state-owned enterprises of African administrations as well. Despite the escalation of investment in the natural extraction industry by affluent transnational companies, “little of the proceeds from the oil wealth eventually get to the majority of the people who need help most.”38 This manipulation is echoed in Julia Maxted’s article, which covers multiple cases across Africa and has an entire section on the situation occurring in Nigeria. Similar to Okeke, she states that there is a “current scramble” for African resources, especially those necessary to generate power, and that this “new imperialism” has left the social, economic, environmental, health, and human rights issues of local communities in the Niger Delta “unfulfilled”.39 Influential state economies such as those of the United States depend heavily on oil for the maintenance of their public and private lifestyles, including an increasingly large percentage imported from West African states like Nigeria so as to lessen their reliance on states from the contentious Middle East.40 Despite this growing demand and income accrued by the Nigerian Federal Government, basic needs are not met in Nigerian communities such as potable water sources, viable opportunities for livelihoods, and functional health or educational facilities, particularly those in the Delta who were promised development by oil companies. This is blamed on the prevalence of corruption and the equivocal reports on profits and local apportionment by state administrations, the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) and international 37 Okeke. op. cit., p. 194. 38 Okeke. ibid., p. 199. 39 Maxted. op. cit. 40 Maxted. ibid. p. 29.

- 21. 21 extraction corporations.41 Maxted emphasizes the damage done to Nigerian communities facing prevailing transnational corporations who consistently leave the population out of essential decision-making processes about their own land. As Section 7 of the Environmental Impact Assessment Decree states, “before the Agency gives a decision on an activity … the Agency shall give opportunity to government agencies, members of the public, experts in any relevant discipline and interested groups to make comment on environmental impact assessment of the activity.”42 Regrettably, tactics are utilized that make public participation of indigenous communities difficult, traditional political structures are obstructed with policies of ‘divide and conquer’, and violent strategies have been employed in order to quell voices of protest in areas of unrest.43 Modern linkages between the governments of less developed nations and the commercial interests of foreign states, which benefit both foreign powers and local elites more than indigenous populations, demonstrate how state resources and policies disregard local interests. The influence of multinational oil companies on economies is strong in the region but the situation has also taken on a local quality in which extraction is supported by elite politicians and officials who stand to gain personally from agreements and unenforced laws.44 This perspective is helpful to our analysis because it encourages a critical view of the actions undertaken by natural extraction industries and the governments who allow them to operate in their territories by framing those arrangements with the historical continuation of profits bought at the cost of human well being. This outlook is necessary to transcend other vested arguments which state that certain economic practices are for the betterment of all; we have seen through our research and through the lens of local peoples that this is not the case. A foundational framework within our research has been the resource curse, which has been a major part of the international discourse since the 1990s, though it has been building in backgrounds since the 1970s.45 Scholars such as Michael Ross and Terry Lynn Karl have elucidated the resource curse, which is also called the “paradox of plenty” and the “King Midas problem” considering the juxtaposition of natural wealth and economic poverty within some 41 Maxted. ibid. p. 34. 42 International Centre for Nigerian Law. 1992. "Environmental Impact Assessment Decree No. 86 1992." 43 Maxted. op. cit., p. 34. 44 Terry Lynn Karl. 2005. "2. Understanding the Resource Curse." Covering Oil. Open Society Institute, New York. p. 116. 45 Angela V. Carter. "Escaping the resource curse." Canadian Journal of Political Science 41, no. 01. p. 216.

- 22. 22 states.46 In Ross’ pioneering article “The Political Economy of the Resource Curse”, he addresses the strong indications that countries which depend heavily upon the extraction of a single resource have a correlative and corrosive relationship with myopic economic strategies. He claims a few reasons for the presence of the resource curse which fall into either the political realm or economic realm. When he wrote this article in 1999, Ross found that of the countries that were immensely in debt and impoverished, 27 out of 36 had economies concentrated on natural resource extraction.47 Economic causes include volatile world markets, deteriorated trade provisions for natural resources, “Dutch Disease” and the feeble support among multiple sectors of the economy.48 Political explanations for detriment involve the poor capacity of government leaders to see beyond the momentary riches to be made, plans that ignore the property rights of locals, policies that encourage the depletion of resources, and the creation of unaccountable rentier states.49 A rentier state is one which “lives from the profits of oil,” or other locally-situated natural resources sold to foreign powers, to a significant extent for its economic stability.50 Because of this concentrated income a dynamic can arise that blends political action and economic policy to a indiscernible and convoluted point. The Mahdavy commentary found in Ross postulated that rentier states damage democracy as the dependence of governments on primary commodity exportation to bolster coffers left them unconcerned with attempts to gather taxes for revenue, and hence allowed them to remain unanswerable to the people of the state.51 When governments become uncaring about their citizens, violence can erupt from clashes with public soldiers, especially when locals attempt to assert their agency. Nigeria is listed as one of the countries where “the rest of the economy, and the rule of law, have largely broken down” due to causes such as those of the political and economic dimensions mentioned above.52 Karl aims to help readers in comprehending the resource curse and its manifestations by first defining what it is not, and then by the parameters of what it is. The resource curse is explained to not be an idea subject to the fluctuating misconceptions which surround it. Some 46 Karl. op. cit., p. 21. 47 Ross. op. cit., p. 322. 48 Ross. ibid., p. 306. 49 Ross. ibid., p. 308. 50 Karl. op. cit., p. 25. 51 Ross. op. cit., p. 312. 52 Ross. ibid. p. 321.

- 23. 23 interpretations conceive that the unfortunate effects of the resource curse, such as substandard rates of social well-being, are endured by any state with any amount of natural abundance. In this article Karl discusses the numerous societal ailments that accompany the failing policies of struggling extraction states, generating environmental degradation, poverty, and intolerable health conditions for local communities.53 But, contrary to the idea that all natural commodities are an offense, states without a substantial economic concentration on extraction do not suffer from the same consequences as those that do. She clarifies the confusion of the term by mentioning that “in its narrowest form, the resource curse refers to the inverse relationship between high natural resource dependence and economic growth rates.”54 Reliance is typically demarcated by comparing the proportion of primary resource exports to the aggregate state exports; if these amounts show that oil or other extracted resources account for 60 to 95 percent of all state exports then the state is considered dependent.55 Her work has found that “oil- and mineral-driven resource-rich countries are among the weakest growth performers, despite the fact that they have high investment and import capacity”56 and the “crux of the problem” is found in the incapable structures of governance.57 She asks a provoking question in her article that highlights the unequal standing of developed and developing countries on the world stage: “If sophisticated governments in the more developed world have trouble executing ambitious interventionist policies, how can governments in less developed countries be expected to administer even more ambitious and complicated policies?”58 This leaning on natural resources is in agreement with Ross by identifying it as a result of rentier states, but differs in outlook by commenting that “not all resources are created equal.”59 Oil is one of the resources considered a specialty “‘point source’” export because of its origins in constricted geological and fiscal jurisdictions.60 For countries which “[look] powerful but [are] hollow” the democratic will of the people is subverted beneath the material aspirations of 53 Karl. op. cit., p. 22. 54 Karl. ibid., p. 23. 55 Karl. ibid. p. 22. 56 Karl. ibid. p. 23. 57 Karl. ibid. p. 25. 58 Karl. ibid. 59 Karl. ibid. p. 23. 60 Karl. ibid.

- 24. 24 government officials who aim to personally profit from the state’s natural oil endowment.61 The corruption that arises from the shadows of greed and mismanagement have come characterize many resource-wealthy, economically poor countries like Nigeria, and led to the present deplorable situation in local communities of the Niger Delta.62 Authors like Karl often speak of a “reality” where “countries that depend on oil for their livelihood are among the most economically troubled, the most authoritarian, and the most conflict-ridden in the world”, but these absolute insinuations are challenged by other studies in the field.63 In the research conducted by Stephen Haber and Victor Menaldo, the affiliation between authoritarianism and primary resource exporters is calculated. Through the design of numerous models and tests which account for variable factors in 168 countries with data ranging from the years 1800 to 2006, they strive to determine how polity has altered in times before and after production.64 With the assortment of differing states, results were categorized by the strength of the association and many were surprisingly recognized as having democratic circumstances improve once financial prosperity was acquired through natural resource exports. Nigeria is classified as an inconclusive C category: Neither Blessed nor Cursed, which denotes the absence of evidence for a significant pattern of autocratic politics before exportation that would indicate resource reliance as the cause of dictatorial governments.65 We found this result surprising as the history of Nigerian government constitutes a picture of inveterate authoritarianism and military rule that has existed for the majority of time since independence and throughout its dealings with mineral extraction. When Olusegun Obasanjo came to office in 1979 he installed an election format and a small stint of civilian rule lasted from 1979 to 1983, but then domineering coups re-emerged and continued until 1999 when civilian rule was again restored and Olusegun Obasanjo became the first democratic elected official voted into the presidency of Nigeria.66 With this timeline demonstrating Nigerian polity, the uncertain impression imparted by Haber and Menaldo seems unsuitable for the reality of past political patterns in Nigeria and their study did not account for these features in a practical way. 61 Karl. ibid. p. 25. 62 Karl. ibid. 63 Karl. ibid. p. 21. 64 Stephen Haber and Victor Menaldo. 2011. "Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism? A Reappraisal of the Resource Curse." American Political Science Review 105, no. 01: 1-26. 65 Haber and Menaldo. ibid. 66 Reuters. 2011. “Timeline: Nigeria's road to democracy.”

- 25. 25 While they conclude that the assumption of the ties among the resource curse and tyrannical regimes are more about correlation than causation in most cases, the “resource blessing” proposed for some states is characterized to be, in fact, quite minimal.67 They even suggest that “the weight of the evidence indicates that scholars might want to reconsider the idea that there is a resource curse.”68 The authors’ capacity to troubleshoot strange outcomes drives them to run assessments for a multitude of scenarios, but also admit to their own shortcomings such as the difficulty of allowing for conditions like revenues supporting dictatorships afterward or how weak states may be prior to the introduction of natural resource trade. These authors are rigorous in their methods, but the lack of definite quality to such quantitative data leaves readers wondering how applicable their conclusions are. It can be understood that not all cases of resource wealth have a direct consequence of autocracy, but these findings don’t reveal much about the actuality of current situations in states who are resource reliant and non-representative. When they state that there may not be a resource curse, they do not provide an alternative approach to understanding the correlation that they agree upon with other scholars. Although we agree on the uncertain nature of social research, we have chosen to place our trust in a larger body of academic work and believe that the resource curse is an actuality in resource-reliant states. 3.2 Corruption Government corruption is, and historically has been, a prominent issue in Nigeria. O.T. Omololu points out that corruption is demonstrated in every aspect of government.69 The aspect that will dominate our research is public revenues. The Government of Nigeria has a reputation for allowing large sums of money to vanish. Accusations and charges of various politicians have materialized, but the issue of embezzlement remains. Richard A. Joseph also tackles this topic. Joseph uses the term “prebendalism” to explain this phenomenon. Joseph describes the term “prebendal” to “refer to patterns of political [behavior] which rest on the justifying principle that such offices should be competed for and then utilized for the personal benefit of office holders as 67 Haber and Menaldo. ibid. 68 Haber and Menaldo. ibid. 69 Omolulu. ibid., p.31

- 26. 26 well as of their reference or support group.”70 In other words, prebendal politics is a scenario where the motive for becoming a politician is the monetary gain to be had. Granted, Joseph does not explicitly state that the “personal benefit” from holding a position in office is a monetary one, but the examples of alleged embezzlement are rampant. He goes on to explain that the (ideally) primary use of the office tends to be neglected in a prebendal situation; the focus is the pursuit of financial gain, and the importance of justice and order is forgotten.71 Omololu cites the National Planning Commission, who claims that corruption and poor transparency have helped to stifle development. He notes how poorly Nigeria ranks in terms of corruption according to Transparency International. As of 2014, Nigeria ranked 136th in the Corruption Perceptions Index out of 175 countries ranked.72 This is an improvement from the 2007 rank of 147 out of 179.73 With that said, these rankings change each year–for example, in 2008, Nigeria jumped up to a rank of 121st out of 180,74 and then back to 130th out of 180 countries ranked in 2009.75 Thus, we are not necessarily seeing a pattern of improvement, but rather merely small shifts not associated with any major governmental improvements. The one consistent pattern is that Nigeria remains in the bottom half of the world in terms of transparency. Omololu specifically notes fraudulent trade, bribery, and abuse of office, among others, as problematic forms of corruption in Nigeria. Embezzlement may fall under the umbrella of abuse of office, and there have been plenty of charges of politicians concerning stolen public revenues. Omololu claims that “corruption and bad governance” were the main justifications for the military when they decided to step into governmental power in Nigeria in 1966. Ironically, the military rule showcased a similar amount, if not a greater amount, of corruption76 –an idea that was similarly explained by Joseph.77 Eventually, Omololu believes, corruption became the norm. What came with this standard of government was a stagnation of development and a drop-off in 70 Richard A Joseph. “Democracy and prebendal politics in Nigeria.” Vol. 56. Cambridge University Press, 2014. p. 8 71 Joseph. ibid. 72 Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2014. 73 Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2007. 74 Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2008. 75 Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2009. 76 Omololu. op. cit., p.31 77 Joseph. op. cit., p.70

- 27. 27 education.78 The recurring point that Omololu makes throughout this paper is that corruption in Nigeria has been the cause for a lack of any development whatsoever. Furthermore, it has also exacerbated the issue of political instability in the country. Sarah Chayes, author of Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security, has some interesting notions that are valuable inclusions in our discussion. Chayes considers the 1980s, when major growth in oil production occurs, as “the first tipping point on the road to acute, systemic corruption.”79 Chayes ties corruption tightly with the growth of oil production in Nigeria. She goes on to note, as Omololu also noted, that while oil production has produced so much wealth, social developments like education and healthcare have not grown at a proportional rate. Chayes also notes that average income is lagging as well. She explains that the wealth from oil production is shared between the federal government and each state government, as well as hundreds of local governments. But this does not do as much good for the state and local governments as it should, because not all of the wealth ends up being accounted for, she explains. She includes some stifling numbers: total sales of crude oil between January 2012 and July of 2013 were missing an estimated US $11 billion, with one estimate of the missing funds to actually be near US $20 billion. Chayes’ findings imply that President Goodluck Johnathan is linked to corrupt practices.80 With all of these political issues, Chayes mentions that the agriculture industry in Nigeria has been troublingly stagnant over the last several decades. She refers to Nigeria as an “oil ‘monoculture,’” pointing out that the manufacturing industry has also slowed down, and as such, the oil industry overshadows all others. According to Chayes, senators in Nigeria make over a million dollars each year, not including any money that may or may not have been embezzled. Chayes identifies a second tipping point of corruption in Nigeria’s history: the switch to civilian rule in 1999. Chayes points out the irony that the first tipping point was partly driven by the lack of accountability caused by military rule in the 1980s.81 Corruption in a civilian government as well as a military government makes for a dilemma that must be acknowledged when discussing solutions for the problem of corruption in Nigeria. 78 Omololu. op. cit. 79 Sarah Chayes. 2015. Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security. WW Norton & Company: p.122 80 President Johnathan will be in office until May of 2015, just after the completion of our paper. The successor, President Muhammadu Buhari, will not make his way into our study as acting president. 81 Chayes. ibid., pp.122-125

- 28. 28 It is perplexing that civilian rule can accommodate a level of corruption similar to that of military rule, but one unquestionable contributor to corruption in a democratically ruled Nigeria is election rigging. Christian Opukri contributes information about election rigging in his paper titled “Electoral Crisis and Democracy in Nigeria.” According to Opukri, all the elections that have taken place in Nigeria since it became independent have been controversial.82 Joseph gives a similar attestation regarding Nigerian elections.83 Opukri also states, not unlike Chayes, that, “[while] the many years of military rule are significant, the years of democratic governance are perhaps more significant, due to the near total lack of democratic values and principles in governance.”84 This is similar to Chayes’ argument, which is essentially that the beginning of civilian rule–her “second tipping point” –is at the very least comparable to, if not more significant than, the growth of oil production, which coincided with military rule as a landmark for corruption. The only difference is that Opukri does not specify the point of oil production growth; he merely compares the time of military rule to the time of civilian rule. Opukri expresses the importance of elections to a democratic system, and that election rigging has run rampant in Nigeria, and, essentially, because of this, democracy has been compromised.85 He points out the 2003 elections specifically as an example: 42 different forms of rigging were recognized. These forms of election rigging varied widely; all were reprehensible, and some used the threat of violence.86 As a result of the corrupt election, several political parties refused to accept the results as legitimate.87 The 2007 election is his second example of an illegitimate election. He draws attention to the failure of some polling stations to ever open at all, as well as others having shortened hours of operation. The list of 2007 polling flaws goes on, once again including violent behavior. Opukri indicates that these practices convinced voters that their participation was irrelevant.88 Chayes describes this situation in the same way, noting the violence associated with the elections as well as the consequential decrease in participation.89 Opukri goes on to note the overwhelming official results of the 2007 presidential elections. 82 Christian O. Opukri. 2013. "Electoral Crisis and Democracy in Nigeria." Journal of Research in National Development 10, no. 3: pp. 178-187 83 Joseph. op. cit., p. 171 84 Opukri. ibid., p. 180 85 Opukri. ibid. 86 Opukri. ibid. 87 Opukri. ibid., p. 181 88 Opukri. ibid., pp. 181-182 89 Chayes. op. cit., p. 126

- 29. 29 Perhaps the most important aspect (as it pertains to our study) of Opukri’s entire paper is his explanation of the relevance of ethnicity. He argues, “It is an acknowledged fact that the Nigerian electoral system is tainted by ethnic considerations and to claim that some of these ethnic leaders scored no more than a few thousand votes even in the states and backyards where their ethnic majority commands the electoral stakes is hard to believe.”90 To put it in a different way, Opukri is noting that these rigged elections are making it so that certain ethnic groups’ votes are not being counted. This point is of the utmost relevance to our research. The corruption present in Nigeria is marginalizing certain ethnic groups.91 3.3 Political Ecology The term political ecology has been around since the 1970s “as a way of thinking about questions of access and control over resources … and how this [is] indispensable for understanding both the forms and geography of environmental disturbance and degradation, and the prospects for green and sustainable alternatives.”92 According to Richard Peet and Michael Watts, political ecology is a combination of ecological concerns with those of political economy. As a result, political ecology provides a perspective that includes the discussion of communities as well as natural resources.93 These authors use this lens to examine the situation in Nigeria. They point out the tremendous amount of wealth generated from oil, and compare it to the per capita annual income, which (as of 2004) was US $290. The point that they are trying to make is that the amount of oil wealth generated should translate to a wealthier society, but such a translation has been lacking. They also point out the estimate of about US $50 billion that has “disappeared” from government revenues as well, implying issues with corruption. Not surprisingly, they claim that living standards have not improved over a span of 44 years–from Nigeria’s independence to the time of publishing.94 Furthermore, they make the claim that the oil producing communities “have benefited the least from oil-wealth.”95 Lastly, these communities, which are all in the 90 Opukri. op. cit., p. 184(1) 91 Opukri. ibid. 92 Richard Peet and Michael Watts. 2004. “Liberation Ecologies: Environment, Development, Social Movements.” p. 6 93 Peet & Watts. ibid., p. 7 94 Peet & Watts. ibid., pp. 274-275 95 Peet & Watts. ibid., p. 275

- 30. 30 Niger Delta, suffer the consequences of oil spills and gas flaring, which occur at a greater rate than anywhere else in the world. These authors make it clear that Niger Deltans suffer from “marginalization” and “neglect”.96 3.4 Local People of the Niger Delta and Oil Ken Saro-Wiwa was an activist working for justice of the Ogoni people in regards to issues surrounding the production of oil. He was dedicated to a non-violent movement for ecological and and social justice, which ultimately resulted in the creation of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP).97 In 1994 Ken Saro-Wiwa along with eight others, who together formed the Ogoni Nine, were arrested for the involvement in the murder of Ogoni leaders. After eight months of imprisonment without access to lawyers, medical care, or family members the Ogoni Nine were brought before a special tribunal. In October 1995 the Ogoni Nine were sentenced to death then executed in November of 1995. MOSOP continues to work for justice under the original vision of Saro-Wiwa. 98 A major aspect of our research is to develop an understanding concerning the relationship between the extraction of oil and the local people of the Niger Delta. “Oil Conflict and Accumulation Politics in Nigeria” written by Kenneth Omeje begins with an overview of the history of oil and conflict in the Niger Delta. It details important facts regarding where the transnational oil companies (TNOCs) operate and whom the companies affect. The article also provides some details on the politics of Nigeria and who is benefiting from the oil profits99 . Other articles do not tend to provide as much basic background information and we believe it is an important aspect in understanding the complex relationship between local people and TNOCs. While this article centers on local ethnic groups generally, “Shell, Nigeria and the Ogoni: A Study in Unsustainable Development I” written by Richard Boele, Heike Fabig and David Wheeler, is focused on the Ogoni people specifically. The Ogoni people are the main ethnic group that we are researching because they are still currently active in conflict with oil companies. Although Omeje’s article has general background information, this article details the history of oil extraction specific to the Ogoni people. This article concentrates on the 96 Peet & Watts. ibid. 97 Remember Saro-Wiwa. 2014. “The Life of Ken Saro-Wiwa.” 98 Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People. 2015. “Ogoni” 99 Kenneth Omeje. 2006-2007.“Oil Conflict and Accumulation Politics in Nigeria” ECSP Report: Issue 12: pp. 44- 49.

- 31. 31 environmental issues that have come with the rise in oil extraction. It also explains how the conflict lead to the execution of Ken Sara-Wiwa and the Ogoni Nine, which was a factor in our group choosing to focus on the Ogoni people.100 The article written by Boele et al. also outlines the lack of, and need for, sustainable development. This is a very important issue for the Ogoni people as well as other local communities.101 Another article discussing local peoples, written by Gabriel Eweje, also highlights the need for sustainable development. The article argues that development is the responsibility of the multinational enterprises and they are both socially and economically responsible for the development to be sustainable.102 Omeje also claims that if the state fails to aid communities in development it is the obligation of oil companies to provide this aid.103 While we believe that the state should be responsible for development and there is a need for sustainable development, we agree that should the state fail, oil companies should be held responsible, to an extent. Given that oil companies have such a large presence and effect on communities, they should provide some aid in the development of communities. Omeje’s article refers to transnational oil companies, however the article by Boele et al. specifically references the Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC), and the article by Eweje discusses multinational enterprises (MNEs) and multinational oil companies (MOCs). It is important to recognize and separate what each article is referring to and the differences between each. Multinational enterprises is the broadest of these terms and includes oil companies as well as other companies.104 Omeje gives examples of TNOCs such as Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobile, and ChevronTexaco,105 indicating that TNOCs can include any oil company working in Nigeria. Multinational oil companies are essentially the same thing as transnational oil companies. SPDC is a single company operating in Nigeria but can be considered a TNOC, MOC and a MNE. 100 Richard Boele, Heike Fabig, and David Wheeler. 2001. "Shell, Nigeria and the Ogoni: A Study in Unsustainable Development I.” Sustainable Development 9, no. 2: pp. 74-86. 101 Boele. ibid. 102 Gabriel Eweje. 2007. "Multinational Oil Companies' CSR Initiatives in Nigeria: The Scepticism of Stakeholders in Host Communities." Managerial Law 49, no. 5/6: 218-235. 103 Boele, op. cit., p.45 104 Eweje, op. cit., p.218-219 105 Omeje. op. cit.

- 32. 32 All three articles bring up the issue of local people not seeing any of the benefits from the extraction and production of oil. Omeje states that despite Nigeria’s oil resources, 80 percent of the revenues only benefit 1 percent of the population and 70 percent of the population lives in poverty, off of less than US $1 a day.106 Boele et al. state that revenue distribution is an issue for many communities including the Ogoni people. The vast majority of the revenue went to the state government whose responsibility was to distribute the wealth, but most communities never saw these benefits.107 Since 1999, the 13% derivation principle states that no less than 13% of oil revenue must go to the oil producing state. As of the year 2000 this revenue refers only to on- shore oil production. The remaining 87% of revenue would go to the central government, which could be distributed to other regions.108 Although this has been the practice since the 1999 Constitution, there has been dissatisfaction among oil producing communities regarding the allocation of funds. There is a call from several communities for the creation of national and state derivation committees to properly manage the funds.109 Eweje goes on the argue that local communities have the right to other benefits such as social services, welfare programs, and community development programs but never saw such benefits.110 Each article makes the point that local communities are suffering from consequences of oil extraction without receiving any benefits. 3.5 Oil Industry and the Environment While we will be focusing on more present issues related to the Nigerian oil industry, it is important to look at the history of Nigerian oil to understand the present. In “Indigenization Versus Domiciliation: A Historical Approach to National Content in Nigeria’s Oil and Gas Industry,” Jesse Salah Ovadia writes about the history of the oil industry in order to help the reader gain an understanding behind current Nigerian oil content laws. Previous content laws theoretically promoted revenues being spent by the Nigerian government in order to empower 106 Omeje. ibid. 107 Boele, Fabig, and Wheeler. op. cit. 108 Ehtisham Ahmad and Raju Singh. 2003. “Political Economy of Oil-Revenue Sharing in a Developing Country: Illustrations from Nigeria.” IMF Working Paper.pp. 1-26. 109 Festus Owete . 2014. “Delta, Ondo Oil Communities Demand Control of Derivation Money.” Premium Times. 110 Eweje. op. cit., 218-235.

- 33. 33 Nigerians with new economic opportunities and give Nigeria control over the oil industry.111 As we have seen in current history, these laws were not successful. In later years, decrees were passed aiming to increase indigenous Nigerian participation in the economy by transferring foreign capital to indigenous hands.112 We will be able to use past Nigerian history to discuss how it has negatively impacted the present. Plundered Nations?: Successes and Failures in Natural Resource Extraction, edited by Paul Collier and Anthony J. Venables, also looks into the history of the Nigerian oil industry. Unlike Ovadia’s literature, the authors look at the management of oil resources throughout history and analyze what decisions were made that ultimately led Nigeria to become a struggling oil state.113 We already know that some of oil revenues are reinvested into infrastructure in Nigeria. During the 1970s, the Nigerian government was focused on reconstruction and the development of human capital, health services, and infrastructure like roads and sea ports.114 Nseabasi S. Akpan, author of “From Agriculture to Petroleum Oil Production: What Has Changed about Nigeria’s Rural Development?,” has different viewpoints on how oil revenues were reinvested back into society. Akpan claims that rural infrastructure has typically been neglected and that infrastructure was, and currently is still focused on major cities. It will be important to look at expenditures of government money to clarify where and how oil revenues were reinvested into Nigerian infrastructure. A major component to our research is the negative environmental effects that come as a result of oil production. Prior to reading, we already knew that oil spills, gas flaring, and land degradation were all harmful impacts oil production have on the environment. In “Coping with Climate Change and Environmental Degradation in the Niger Delta of Southern Nigeria,” gas flaring and oil spills are discussed in depth and their ultimate consequences to farmlands, rivers, and the ocean.115 We found that oil spills, gas flaring, and acid rain not only affect the 111 Jesse Salah Ovadia. 2012. "Indigenization vs. Domiciliation: A Historical Approach to National Content in Nigeria's Oil and Gas Industry." African Political Economy: The Way Forward for 21st Century Development. 112 Jesse Salah Ovadia. ibid. 113 Paul Collier and Anthony J. Venables, eds. 2011. Plundered nations?: successes and failures in natural resource extraction. Palgrave Macmillan. 114 Collier and Venables. ibid 115 Etiosa Uyigue, and Matthew Agho. 2007. "Coping with climate change and environmental degradation in the Niger Delta of southern Nigeria." Community Research and Development Centre Nigeria (CREDC).

- 34. 34 environment, but the livelihood of local peoples as well.116 The book Oil, Environment and Resource Conflicts in Nigeria, edited by Augustine Ikelegbe asks interesting questions in the introductory section: Since oil and gas are exhaustible resources, what happens when they are exhausted and when no revenue inflows would be expected to the region?...what would happen as the land and waters of the region are devastated, livelihood sources have been destroyed, social lifestyles have been perverted and productive orientations have been disoriented?117 While this paper is about the facts of the oil industry in Nigeria, it poses interesting “what-if” scenarios, should the oil industry not make strides to better its infrastructure and environmental regulations. Along with posing consistent statistics with other works of literature, this will enable us to draw conclusions on our own, on the negative impacts of oil production. 116 Uyigue and Agho. ibid. 117 Augustine Ikelegbe ed. 2013. Oil, environment and resource conflicts in Nigeria. Vol. 7. LIT Verlag Münster: 4.

- 35. 35 4. Case Study 4.1 Petrol and Layered Logistics The Federal Government of Nigeria and the multinational oil companies that operate in Nigeria are conspicuously intertwined, resulting in an obscure partnership, multi-level financial arrangements, and a system of property rights that values the state as an entity more than individual indigenous stakeholders. Oil discovery in 1956 brought a new and powerful dimension to the colonial economy and after Nigeria gained independence, it continued to be an important factor in fiscal security. Tenure systems for land and the ownership of mineral wealth was realized to be crucial in these processes, and the new government began to pass laws regarding these issues. In 1969 the Petroleum Decree was enacted, placing the gas and oil supplies of the country under the authority of the federal government. In a related legislation, the 1978 Land Use Decree placed all land of any type under national control, essentially using nationalization as a substitute for the long-standing rules of customary land ownership.118 Rather than “negotiating directly with oil companies over access to land and compensation” as was done before the decrees, the power of bargaining for communities was usurped by local and state institutions.119 Claims of “overriding public interest” after the 1978 statute also enabled the federal government to easily appropriate lands for the construction of pipelines and extraction projects.120 Many communities struggle with these laws which do not recognize the land that members live and work on, and therefore the minerals beneath the land, as territories owned by those who have inhabited it for generations. These decrees, by allowing the state to have absolute proprietary rights, leave communities living on resource-rich lands subject to the complete control of state economic interests, and the uncertainty of a stable residence if their area is seen as too valuable for just human occupancy. The Federal Government of Nigeria began to seek dominion within all oil industry aspects, beyond only mineral rights. Nigeria joined the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1971, becoming part of an exclusive group of countries with the ability to regulate oil output and influence prices around the world.121 OPEC insists that member states 118 P. Francis and S. Sardesai. 2008. “Republic of Nigeria Niger Delta Social and Conflict Analysis.” World Bank. p. 12. 119 P. Francis and S. Sardesai. ibid. 120 P. Francis and S. Sardesai. ibid. 121 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). 2015. “Nigeria Facts and Figures.”

- 36. 36 engage in all stages of petroleum production as a majority associate as much as possible. Therefore, in order to begin taking back privileges from foreign companies, the federal government created the Nigerian National Oil Corporation (NNOC) in 1971.122 “The NNOC was empowered to acquire any asset and liability in existing oil companies on behalf of the Nigerian government,” and throughout the 1970s, the NNOC recovered allowances from numerous transnational oil corporations.123 The federal establishment managing petroleum commerce became the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) in 1977 and “inherited the commercial activities of the NNOC.”124 Although the NNPC has some oversight capacity, the majority of regulation is under the jurisdiction of the Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources and their Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR).125 Joint ventures solidified between the NNPC and transnational oil corporations ensure that the state government has a 55% to 60% “participatory interest,” and therefore some say in the procedures performed by oil companies.126 Agreements such as these joint ventures are the most common type of business agreement in the Nigerian oil industry, and are so prevalent that they constitute 95% of Nigerian petroleum and natural gas activities.127 The most prominent multinational corporations, which make up almost 97% of production endeavors, include well-known names like Shell, Chevron/Texaco, and ExxonMobil.128 Before companies can operate in a way that earns profits they must obtain three permissions granted by the Minister of Petroleum Resources. The authorizations encompass the Oil Exploration Licence (OEL) which is “necessary to conduct preliminary exploration surveys,” the Oil Prospecting Licence (OPL) which begins contract agreements with the government, and the Oil Mining Lease (OML) which allows commercial extraction in an area for 20 years.129 Since 1973, deals with conglomerates have had another common aspect: they are considered to be Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs) that place the risk of exploration on companies, whether 122 Olajumoke Akinjide-Balogun. 2001. “Nigeria: Legal Framework Of The Nigerian Petroleum Industry.” Mondaq. 123 Olajumoke Akinjide-Balogun. ibid. 124 P. Francis and S. Sardesai. 2008. “Republic of Nigeria Niger Delta Social and Conflict Analysis.” World Bank. p. 15. 125 Olajumoke Akinjide-Balogun. op. cit. 126 Olajumoke Akinjide-Balogun. ibid. 127 P. Francis and S. Sardesai. 2008. “Republic of Nigeria Niger Delta Social and Conflict Analysis.” World Bank. p. 33. 128 Olajumoke Akinjide-Balogun. 2001. “Nigeria: Legal Framework Of The Nigerian Petroleum Industry.” Mondaq. 129 Olajumoke Akinjide-Balogun. ibid.

- 37. 37 oil is found or not.130 Theses types of agreements also split discovered oil into a few categories with varying importance: "Royalty Oil" pays concession rents and royalties, "Cost Oil" covers the cost of operations, "Tax Oil" gives to the government through the Petroleum Profit Tax (PPT), and "Profit Oil" leaves what is left to divide as percentages between all partners of an agreement.131 Royalties and the Petroleum Production Tax are amassed by the Federation Inland Revenue Board as an act of government and, with profits made, comprise the total oil income for Nigeria.132 Revenues are apportioned among many parties and the numerous layers to agreement and payment processes have not been successful in distributing income effectively, or improving the lives of most Nigerians. The equitable allocation of revenues gathered from the oil industry has been a point of contention for many communities in the Delta for many years. A derivation formula was established from the outset of oil production in 1958 which set revenues to be distributed to extraction communities at a rate of 50%, the Federal Government of Nigeria at 20% and the Distributable Pool Account, created to apportion funds to states from the federal sphere, at a rate of 30%. Since that time the percentages have been erratic as more states have been created, transitions of government rule have occurred, and offshore drilling has become the domain of the federal administration.133 In 1999 the new constitution, under the category of Public Revenue section 162, speaks to a ‘Federation Account’, previously the Distributable Pool Account, which accumulates all revenue by the federal government, apart from certain officials’ income taxes, and allocation is decided after the President councils with the Revenue Mobilization Allocation and Fiscal Commission (RMAFC). The President and his council then consider “population, equality of States, internal revenue generation, land mass, terrain as well as population density” into choices of disbursement. The article goes on to state that “the principle of derivation shall be constantly reflected in any approved formula as being not less than thirteen per cent of the revenue accruing to the Federation Account directly from any natural resources.”134 The arguments surrounding this number only serve to hinder the formation of an improved system, 130 Akinjide-Balogun. ibid. 131 Akinjide-Balogun. ibid. 132 Akinjide-Balogun. ibid. 133 P. Francis and S. Sardesai. 2008. “Republic of Nigeria Niger Delta Social and Conflict Analysis.” World Bank. p. 27. 134 The Federal Republic of Nigeria. 1999. “Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.”

- 38. 38 and obscure other issues of marginalized communities, mismanaged distribution and inadequate well-being which persist despite large profits of the oil industry. 4.2 Impaired Institutions The legacies of colonialism have left their mark upon the political and social structures that dominate Nigeria today, and the formation of a resource dependent state since independence has not enabled an internally stable government to be built. The indirect model of colonization exercised by the British meant that although they pulled strings in the capital, local chieftaincies and leaders who were friendly to the interests of Britain were bestowed the privilege to continue acting as authority figures in communities, thereby blurring the understanding of the situation for rural communities.135 Identities held dear by local peoples and nationalistic ideologies under colonial rule brought some civil rights, but also a disconnect with the definition of who was the bearer of customary rights. Nigeria was then made to create statutory regulations to “decide which ethnic groups were indigenous and which were not [as] a basis for political representation.” This process is said to have “convert[ed] ethnicity into a political force”, although one may argue that such systems had been instigated from the beginning of British rule.136 In the post-independence era the three states of the federation, which had been created under colonial rule and favored the three most prominent ethnic groups, were still the only officially acknowledged regions, but disagreement over these lines came soon after liberation. The Ogoni Central Union had arisen prior to independence and formed the Ogoni Native Authority in 1947 to advocate for separate space, and was reluctantly lumped into the Eastern Region where the Ogoni people suffered “tremendous neglect and discrimination” at the hands of the prevailing Igbo people in the area.137 In order to address the worries of smaller ethnic groups in the region who were being underrepresented, the Willink Commission was entrusted with the task of exploring local concerns stemming from this issue in 1958 as the prospect of Independence approached.138 Despite the proposal for the outlining of new states, the 135 P. Francis and S. Sardesai. 2008. “Republic of Nigeria Niger Delta Social and Conflict Analysis.” World Bank. p. 57. 136 Michael Watts. 2004. "Resource curse? Governmentality, oil and power in the Niger Delta, Nigeria." p. 73. 137 Watts. ibid. p. 67. 138 Francis and Sardesai. op. cit., p. 30.