MCHE 484 Senior Design Final Report Rev_8

- 1. MCHE 484 Final Design Report Instructor: Dr. Christopher Dalton Advisor: Dr. Joshua Vaughan Authors: Daniel Newman, Jonathan Orta, Joel Weber, Tyler Kragle

- 2. Date: May 1, 2015 2

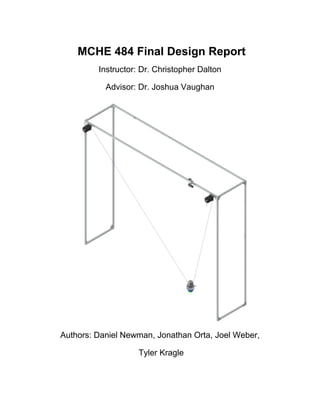

- 3. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The project defined in this report consist of a Cable-Drive Parallel Robot, ( CDPR). There are many different configurations, constraints and degrees of freedom that can applied to these robots. A CDPR design consist of a frame with various motors that drive cables operated by a control sequence to accurately maneuver a central module; Skycam is an example of this application. With the time allotted, the best interest of the group was to choose a 2D planar application because of time and monetary means. Design consisted of using a microcomputer to control the speed and direction of the motors while using a micro-stepper to provide vibration control to the motor. Other aspects of the design included necessary static and dynamic calculations in order to select the appropriate motor torque. Upon completion the CDPR consist of one motor, able to move in 2D planar motion The objective is to eventually apply this 2D planar design into a more versatile 3D application. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 Executive Summary...........................................................................................................................1 1

- 4. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 2.0 Introduction........................................................................................................................................3 3.0 Background Research........................................................................................................................4 3.1 Versaball..........................................................................................................................................................5 3.2 Stepper Motor/Microstep Driver................................................................................................................6 4.0 Design Process....................................................................................................................................6 4.1 Design Criteria...............................................................................................................................................6 4.2 Design Evaluation Process...........................................................................................................................7 4.3 Designs Created.............................................................................................................................................7 4.4 Design Selection............................................................................................................................................8 5.0 Final Design Details..........................................................................................................................9 5.1 Mechanical Design......................................................................................................................................10 5.1.1 Motor Selection............................................................................................................................................10 5.1.2 Design of Fabricated Components...............................................................................................................10 5.1.3 Aluminum Structure Design......................................................................................................................11 5.1.4 Pneumatics...................................................................................................................................................11 5.1.5 Constraint of the Versaball..........................................................................................................................12 5.2 Electronic Design.........................................................................................................................................13 6.0 Design Testing and Results...........................................................................................................14 6.1 Structure Construction...............................................................................................................................14 6.2 Motor Testing...............................................................................................................................................14 6.3 Pneumatics Testing.....................................................................................................................................14 7.0 Cost Analysis....................................................................................................................................14 7.1 Vendor Breakdown.....................................................................................................................................14 7.2 Labor Breakdown........................................................................................................................................15 8.0 Conclusions.......................................................................................................................................16 9.0 Appendix...........................................................................................................................................18 9.1 Appendix I – Motor Calculations.............................................................................................................18 9.2 Appendix II – Structure Calculations......................................................................................................20 9.3 Appendix III – Fabrication Drawings.....................................................................................................24 9.4 Appendix IV – Design Tools ....................................................................................................................28 9.4.1 House of Quality..........................................................................................................................................28 2

- 5. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 9.4.2 Function Tree...............................................................................................................................................29 9.5 Appendix V – Parts List..............................................................................................................................32 10.0 References.......................................................................................................................................34 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1 - Morphological Chart (a)........................................................................................................7 Figure 2 - Morphological Chart (b).......................................................................................................8 Figure 3 - Design Evaluation Matrix.....................................................................................................9 Figure 4 - NEMA 34 Motor Torque Curve.........................................................................................10 Figure 5 - Versaball Constraints..........................................................................................................13 Figure 6 – Beaglebone Black................................................................................................................14 Figure 7 - Vendor Cost Breakdown.....................................................................................................15 LIST OF TABLES 2.0 INTRODUCTION The field of cable-driven robotics possesses vast capabilities and opportunities. Over the past several decades, a number of studies have shown that this field of robotics has great potential. Simply put, the cable-driven robot referred to here is a set of n cables loaded in tension by n motors. These cables are arranged such that they can be wound or unwound to manipulate a focal object called the end- effector. These types of robots are considered in many ways to be better than the previous option – serial manipulators – which are made using a rigid set of links and joints. The most common example of this device is a robotic arm. Cable driven robots have advantages such as higher 3

- 6. MCHE 484 Final Design Report acceleration, lower mass, greater range of motion, and adaptability. Their shortcomings include the lack of a cable’s ability to provide negative (compressive) tension. This means that a cable can pull an object, but not push it without the interference of other mechanisms. Cable-driven robots are used in many applications today such as construction, rehabilitation, and entertainment. Because of its wide range of uses, there are numerous different designs and theories in this field. Since this is a fairly new field of robotics, cable-driven robots are still being designed and tested in different forms of industry. With this new technology, these industrial settings can hopefully be made safer and more efficient. Our current design project is to analyze and design the interface of all components involved in this cable-driven robotic process, as well as implement a grasping mechanism to be transported by the cables. Our specific objectives are the following: • Create a simple & lightweight design • Utilize a Versaball® • Lift objects of various shapes and sizes • Operate in a 10ft X 2ft X 8ft workspace • Single user operation via connection as well as online interface • Operate through a 110V ordinary outlet • Implement the recording of user commands, location, & cable movement • Programmable movement We focus our research and design based on using these robots to enhance an inside manufacturing environment. The following article shows or research, process, and design towards a cable-driven robot that will accomplish these goals and objectives. 3.0 BACKGROUND RESEARCH The focus of selecting how to design a cable-driven parallel robot is to eliminate the constraints of rigid parallel robots. These robots are applicable for factory settings, astronomical observation, structure building devices, rescue, rehabilitation, etc. The advantages cable-driven parallel robots have are large workspace, ease of reconfiguration, high speed motion, and high payload to weight ratio [1]. The cable-driven parallel robots fall into two categories: fully-constrained and under- constrained [2]. The fully-constrained cable robots can control all its motions solely by cable forces, while in the under-constrained situation, gravity is necessary to serve as the constant external force that controls the end-effector’s degrees of freedom [3]. A control scheme must be implemented in 4

- 7. MCHE 484 Final Design Report order to control the cable length, where a feedback control in the cable length is used for coordination to realize the desired cable length corresponding to a desired position of an end- effector [4]. As far as how the cable will be displaced, one of the more successful ways of achieving this is by using motorized drums that can coil or uncoil the cables [5]. Since cables can only pull and not push, n+1 cables must be used for n degrees of freedom [6]. One thing that has not been done before is regarding the fully-constrained design where cables provide the downward force. The current way to achieve the downward force is, as stated, by using cables or by relying on gravitational forces, which limits workspace by having additional cables and adds constraints to current designs. Similar projects include the Arecibo Observatory, the world’s largest single largest aperture telescope. A system of 18 static cables, reinforced by three towers, suspends a 900-ton platform above the dish that all act as the support system of the dish [7]. Cable-driven parallel robots can serve as the end-effector of a camera robot, which offers a valuable solution for viewing over the sky [8]. Other potential areas of employment for these robots include airplane part assembly, giant ship assembly, and rocket launch simulation [9]. A low gravitation application has been used to simulate motion in low gravity conditions, which is helpful in aerospace engineering, especially in simulating docking, launch, and landing processes [10]. The use of these robots has been implemented in rehabilitation assisting patients with medical issues. Two types of robots are used for this application where a traction-type is used for example to suspend a broken arm by using cables [11] while the other method is an exoskeleton-type robot to assist and accelerate the healing process with the same injury [12]. One application that is similar to our design is FALCON-7. This project uses four motors that control the lengths of the four separate cables to move an end-effector around in a three-dimensional space [13]. 3.1 Versaball For the end effector used in the design of our cable-driven parallel robot, a robotic gripper, VERSABALL, is to be used to pick up objects and translate them in an operational space. This particular robotic gripper uses a method of jamming granular materials by vacuum-packing. The way this phenomenon, called jamming transition, works is that granular materials or particles can flow and act like a fluid when loosely packed, but the materials interlock to become rock-solid when packed together. This gripper takes advantage of this behavior so that when the gripper is soft, it can be pressed against an object, conforming to take the object’s shape. Preceeding this step is when the gripper vacuum-hardens to grasp the object firmly [14]. 5

- 8. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 3.2 Stepper Motor/Microstep Driver A stepper motor is a type of brushless DC motor that divides a full rotation into a number of equal steps. The motor’s position can then be commanded to move and hold at one of these steps without any feedback sensor, like an open-loop controller. The important property of a stepper motor is that in converts input pulses into a precisely defined increment in the shaft position. These pulses move the shaft through a fixed angle. Inside the motors are multiple toothed electromagnets arranged around a gear-shaped piece of iron. To control the electromagnets, a microcontroller is typically used. By having a higher number of teeth in the electromagnets allows for a higher resolution in the motor, and by having a higher resolution, the precision of the shaft increases. For the application of the robot, having a stepper motor with a high resolution is ideal since operating the VERSABALL to move to precise locations in the operating space is one of the more focused design criteria. To increase the resolution of the motor, a microstep controller is used to smooth out the motor operation. This microstepping process is done by approximating a sinusoidal AC waveform. Although, the accuracy drops by using a microstepper, the mechanical noise is reduced, mechanical actuation is gentler, and resonance problems are reduced. The real advantage to using this device is that by maintain synchronization of the system will provide less wear and tear on the motor [16]. 4.0 DESIGN PROCESS 4.1 Design Criteria The task of providing a cable-operated means of lifting, transporting, and releasing various objects using an 110V outlet was given. Under this objective specific crieteria was given to implement into the design. The most essential requirements of this cable robot were the following: • Remotely operable via internet interface • Ability to record user commands, location, and cable movement • Cable movement prompted by pre-programmed or manual input commands • Include limiting and kill switches Through these objectives, as well as other customer requirements, a House of Quality was created. This was used to organize and relate the customer requirements and functional requirements of our specific project. All criteria was then weighted based on suggested importance. This was the first step in the design process and showed the importance of certain restraints versus others. 6

- 9. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 4.2 Design Evaluation Process The next step in the design process was to use this House of Quality to create a Function Tree. The purpose of the function tree was to consolidate all the functions of the robot into more simple sub- functions that can be accomplished. The first level of sub-functions included transportation, user interface, and data recording. These three sub-functions contain all needed functions in the entire project. The sub-functions in the Function Tree would then simplify and direct the remaining design process. 4.3 Designs Created After these sub-functions are created, they can be used to begin the various designs of the cable robot. This is initiated by a Morphological Chart. A Morphological Chart is simply a table that displays the resolutions of each sub-function through various designs. Since no designs have been chosen yet, this should include all possible solutions. Each separate sub-function was then matched to create alternative design concepts. Figure 1 - Morphological Chart (a) 7

- 10. MCHE 484 Final Design Report Figure 2 - Morphological Chart (b) Four separate design concepts were created. The main difference between them was each method of grasping an object. These methods included a Versaball, mechanical claw, and magnet. The other important differences were its specific motor usage and process of user interface/control. Other requirements were met very similarly based on prior instructions from the customer such as Python and PC-based Datalogger. 4.4 Design Selection With alternative design concepts created, the next task was to then decide on the most optimum design. This was accomplished using an Evaluation Matrix. The Evaluation Matrix gives a means to rate each concept based on its execution of the customer requirements. Through the three levels of rating, the under- constrained Versaball concept was found to best satisfy theour objectives and requirements set by this design. This is proven by its accomplishment of the most important needs. 8

- 11. MCHE 484 Final Design Report As shown in the Evaluation Matrix, the under constrained Versaball concept met the highest weighted requirements such as transportation, user interface, and safety. Figure 3 - Design Evaluation Matrix 5.0 FINAL DESIGN DETAILS After the building blocks of the final design were selected, the final design for this prototype was realized. Two primary elements of this design fall under the scope of the project: electronic control and mechanical structure. An important distinction must be made for the final design of this project. Where the previous design documentation dictated a three-dimensional operational space, the design that follows assumes a prototype assembly that will operate in a plane. This design is meant to serve as a proof-of-concept where the initial objectives will not all be met, but given the constraints of budget, time, and engineering know-how, a baseline can be created from which future teams can build and improve to ultimately meet those objectives. 9

- 12. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 5.1 Mechanical Design Two constraints were initially given with respect to the mechanical design: the 3.5” Versaball must be used and 80-20 aluminum frame will create the structure. Additionally, two solenoid valves and their associated fittings and hose were purchased prior to the commencement of this design. The pneumatic control of the Versaball would originate from a compressed air source in the lab where the structure would be constructed. 5.1.1 Motor Selection With these constraints in place, the first major design selection was the motor that would power the cable assembly. A calculation was performed to determine the required torque on the motor to lift and accelerate the Versaball. See Appendix I for the associated calculation. It was concluded from this calculation that a motor with an available torque in excess of 800 oz-in would be necessary. A NEMA 34Y Stepper motor from Anaheim Automation was selected. This motor is part of a package sold by the vendor which is meant to be a complete solution to power and control the motor. The available documentation from the vendor indicates that this motor has access to the torque necessary at rotational speeds that are reasonable for the desired application (Figure 11 ). Figure 4 - NEMA 34 Motor Torque Curve 5.1.2 Design of Fabricated Components 1 PKG-342-MBC12-PS-CBL System Diagram And Specifications, Anaheim Automation 10

- 13. MCHE 484 Final Design Report For this design, multiple components needed to be fabricated as opposed to being purchased from a vendor. These components include adapters that allow mounting of the motors and valves to the frame as well as an adapter that allows for additional ballast to be added to the Versaball. In order to confidently send design drawings to a fabricator, the appropriate components were modeled in Autodesk Inventor and dimensions were confirmed. Appendix III shows the final design drawings for the three components that were fabricated for this design. 5.1.3 Aluminum Structure Design A number of 1” extrusions of aluminum T-Slotted frame2 were supplied for the construction of the prototype. Given a design area of 10’x8’x2’, a method of assembling the frame needed to be evaluated. The primary loads considered were the motors and the tension evaluated per Appendix I. The main concern for the structure would lie in the cross member where the motor and hoses were supported. With most of the weight of the assembly lying in the Versaball, the motors were designed to be located as close to the L-Brackets as possible. This location will serve to alleviate any excess moment and therefore any excess displacement and stress in the assembly. Per calculations in Appendix II, it was concluded under the assumptions of this design that the modeled structure would be acceptable. An understood complication is the potential deflection in the frame. Given time and budgetary constraints, the risks of deflection would be acceptable. 5.1.4 Pneumatics The pneumatic control of the Versaball was also a major design concern for the prototype. The facility in which the prototype would be built contains a pressurized air outlet which would supply the pneumatic force required to operate the Versaball. Additionally, several fittings, valves, and lengths of hose were supplied to the team. Once again, an analysis of the 3D CAD model assisted in gaining an understanding of the pneumatic components. Given the very large operational area along with the fact that two lines of hose would need to be supplied to the Versaball, it was decided to use coiled lengths of hose from the top cross-member of the frame to the Versaball outlets. These coiled hoses would be mounted to a linear bearing on that member, which would allow them to 2 McMaster P/N 47065T101 11

- 14. MCHE 484 Final Design Report transverse its length as the Versaball moves. A Filter/Regulator was purchased to help regulate the input air, and several fittings were purchased to allow for the hose to run from the regulator to the valve. 5.1.5 Constraint of the Versaball The constraint of the end-effector in a cable-controlled design is a huge concern. For the prototype specified by this design, time and budget were once again strong factors in the decision to move forward with an under constrained design (Figure 5). As the figure below shows, the two cables that will run from the motors will give stability in the X and Y directions while also providing a small restoring moment in the Y and Z directions. By further analyzing the Versaball, it becomes apparent that the interaction between the assembly and the force of gravity is a stable one, meaning that a force in the Z direction (out of the page) or a moment along the X direction will be restored by gravity. A full vibration analysis would allow for a more thorough understanding of the stability of the assembly and increase the effectiveness of a controller. Regardless, it is apparent that while this system is technically stable within a certain limit, severe limitations will exist in its effectiveness and application. 12

- 15. MCHE 484 Final Design Report Figure 5 - Versaball Constraints 5.2 Electronic Design Two main aspects of the design needed to be controlled electronically: the Versaball and the motors. To gain this control, the Beaglebone board was chosen (Figure 6). The Beaglebone is a microcomputer that readily accepts Python scripted code and can be used to control several inputs and outputs. A Raspberry Pi and PiFace Digital were initially considered for this purpose, but when it was discovered that this hardware would not be able to generate an output signal in the range of frequencies that the motors would require, a decision was made to change to the Beaglebone. Using Python scripted code on this board would be facilitated by the fact that a Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) function library is readily available. 13

- 16. MCHE 484 Final Design Report Figure 6 – Beaglebone Black 6.0 DESIGN TESTING AND RESULTS 6.1 Structure Construction 6.2 Motor Testing 6.3 Pneumatics Testing 7.0 COST ANALYSIS 7.1 Vendor Breakdown TIn this section contains a detailed report of all monetary expenditures recorded in the design project. The project followed a typical design sequence where all design was formally completed and analyzed before any purchases were made. Major expenses like the Versaball, Stepper motor system and 20x20 framing were supplied by Dr. Vaughan. BOSCO Machine Shop also donated three fabricated parts. These items are included in the budget but were not directly ordered by the team. McMaster was the supplier of choice for most remaining parts. McMaster made it simple to 14

- 17. MCHE 484 Final Design Report choose parts with nice CAD filesdiagrams and part numbers for every item. Depicted below is a PDF of every item included in the project including part number, estimated cost and vendor. Figure 7 - Vendor Cost Breakdown The project came to a total of about $6,000. If this designe group were to have involved abuilt the 3D Cable Drive Robot, withhaving four motors, the estimated cost would come out to $8,000. The reason the cost is not significantly more is because for the 3D version only needs two additional motors and a bit more hardwarecouple of brackets. The 2D planar model we currently havebuilt in this design is not hardwould rather easily be modified to revise into incorporate three dimensional movement. A comprehensive list of purchased components can be found in Appendix V. 7.2 Labor Breakdown Month Total time January 41 February 25 March 54 April 93 May 0 Total Hours 213 15

- 18. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 8.0 CONCLUSIONS While the design operated as projected, there were also some limitations that were unforeseen. The operation of the motors via microcomputer performed without incident by providing proper coding to control the according motor speed and direction. However, due to monetary limitations, only one motor was available to use, essentially eliminating the proposed two-dimensional application. Adding another motor and altering the code would allow for the two-dimensional movement desired. Although two-dimensional movement was limited, success was still achieved because the project’s objectives were completed. As far as future work for this design, it is on the right path to taking the succeeding steps into two-dimensional and three-dimensional designs that are more practical in real-world applications. 16

- 19. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 17

- 20. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 9.0 APPENDIX 9.1 Appendix I – Motor Calculations 18

- 21. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 19

- 22. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 9.2 Appendix II – Structure Calculations 20

- 23. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 21

- 24. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 22

- 25. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 23

- 26. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 9.3 Appendix III – Fabrication Drawings 24

- 27. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 25

- 28. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 26

- 29. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 27

- 30. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 9.4 Appendix IV – Design Tools 9.4.1 House of Quality 28

- 31. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 9.4.2 Function Tree 29

- 32. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 30

- 33. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 31

- 34. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 9.5 Appendix V – Parts List 32

- 35. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 33

- 36. MCHE 484 Final Design Report 10.0 REFERENCES [1][2][3] X. Tang “An Overview of the Development for Cable-Driven Parallel Manipulator,” Advances in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 2014, http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ame/2014/823028/ [4] S. Kawamura, H. Kino, and C. Won, “High-speed manipulation by using parallel wire-driven robots,”Robotica, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 13–21, 2000. [5][6] S. Kawamura et al. Development of an ultrahigh speed robot FALCON using wire driven system. In IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation, pages 215-220, Nayoga, 25-27 May 1995. [7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arecibo_Observatory. [8] http://www.skycam.tv. [9] X. Tang “An Overview of the Development for Cable-Driven Parallel Manipulator,” Advances in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 2014, http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ame/2014/823028/ [10] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rendezvous_Docking_Simulator. [11] G. Rosati, M. Andreolli, A. Biondi, and P. Gallina, “Performance of cable suspended robots for upper limb rehabilitation,” in Proceedings of the IEEE 10th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR '07), pp. 385–392, IEEE, June 2007. [12] G. Yang, H. L. Ho, W. Chen, W. Lin, S. H. Yeo, and M. S. Kurbanhusen, “A haptic device wearable on a human arm,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics, vol. 1, pp. 243–247, December 2004. 34

- 37. MCHE 484 Final Design Report [13] S. Kawamura et al. Development of an ultrahigh speed robot falcon using wire driven system. In IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation, pages 215-220, Nayoga, 25-27 May 1995. [14] Eric Brown et al., Universal robotic gripper based on the jamming of granular material, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1003250107 [15] http://www.micromo.com/microstepping-myths-and-realities 35