Cancer renal

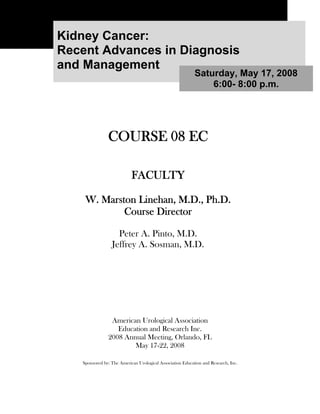

- 1. Kidney Cancer: Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Management Saturday, May 17, 2008 6:00- 8:00 p.m. COURSE 08 EC FACULTY W. Marston Linehan, M.D., Ph.D. Course Director Peter A. Pinto, M.D. Jeffrey A. Sosman, M.D. American Urological Association Education and Research Inc. 2008 Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL May 17-22, 2008 Sponsored by: The American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc.

- 2. Meeting Disclaimer Regarding materials and information received, written or otherwise, during the 2008 American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. Annual Meeting Instructional/Postgraduate MC/EC and Dry Lab Courses sponsored by the Office of Education: The scientific views, statements, and recommendations expressed in the written materials and during the meeting represent those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily represent the views of the American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc.® Reproduction Permission Reproduction of all Instructional/Postgraduate, MC/EC and Dry Lab Courses is prohibited without written permission from individual authors and the American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. These materials have been written and produced as a supplement to continuing medical education activities pursued during the Instructional/Postgraduate, MC/EC and Dry Lab Courses and are intended for use in that context only. Use of this material as an educational tool or singular resource/authority on the subject/s outside the context of the meeting is not intended. Accreditation The American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education (CME) for physicians. The American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. takes responsibility for the content, quality, and scientific integrity of the CME activity. CME Credit The American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. designates each Instructional Course educational activity for a maximum of 1.5 AMA PRA Category 1 credits™; each Postgraduate Course for a maximum of 3.25 AMA PRA Category 1 credits™; each MC Course for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 credits™; each EC Course for a maximum of 2.0 AMA PRA Category 1 credits™; each MC Plus Course for a maximum of 2.0 AMA PRA Category 1 credits™; and each Dry Lab Course for a maximum of 2.5 AMA PRA Category 1 credits™. Physicians should only claim credits commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Disclosure Policy Statement As a provider accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc., must insure balance, independence, objectivity and scientific rigor in all its sponsored activities. All faculty participating in an educational activity provided by the American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. are required to disclose to the audience any relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest to the provider. The intent of this disclosure is not to prevent a faculty with relevant financial relationships from serving as faculty, but rather to provide members of the audience with information on which they can make their own judgments. The American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. must resolve any conflicts of interest prior to the commencement of the educational activity. It remains for the audience to determine if the faculty’s relationships may influence the educational content with regard to exposition or conclusion. When unlabeled or unapproved uses are discussed, these are also indicated. Evidence-based Content As a provider of continuing medical education accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), it is the policy of the American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. to review and certify that the content contained in this CME activity is evidence-based, valid, fair and balanced, scientifically rigorous, and free of commercial bias.

- 3. 2008 AUA Annual Meeting 08 EC Kidney Cancer: Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Management 5/17/2008 6:00 - 8:00 p.m. Disclosures According to the American Urological Association’s Disclosure Policy, speakers involved in continuing medical education activities are required to report all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest to the provider by completing an AUA Disclosure Form. All information from this form is provided to meeting participants so that they may make their own judgments about a speaker’s presentation. Well in advance of the CME activity, all disclosure information is reviewed by a peer group for identification of conflicts of interest, which are resolved in a variety of ways. The American Urological Association does not view the existence of relevant financial relationships as necessarily implying bias, conflict of interest, or decreasing the value of the presentation. Each faculty member presenting lectures in the Annual Meeting Instructional or Postgraduate, MC or EC and Dry Lab Courses has submitted a copy of his or her Disclosure online to the AUA. These copies are on file in the AUA Office of Education. This course has been planned to be well balanced, objective, and scientifically rigorous. Information and opinions offered by the speakers represent their viewpoints. Conclusions drawn by the audience members should be derived from careful consideration of all available scientific information. The following faculty members(s) declare a relationship with the commercial interests as listed below, related directly or indirectly to this CME activity. Participants may form their own judgments about the presentations in light of full disclosure of the facts. Faculty Disclosure W. Marston Linehan, M.D., Ph.D. Course Director National Cancer Institute: Meeting Participant or Lecturer Peter A. Pinto, M.D. Nothing to disclose Jeffrey A. Sosman, M.D. Nothing to disclose

- 4. Disclosure of Off-Label Uses The audience is advised that this continuing medical education activity may contain reference(s) to unlabeled or unapproved uses of drugs or devices. Please consult the prescribing information for full disclosure of approved uses. Faculty and speakers are required to disclose unlabeled or unapproved use of drugs or devices before their presentation or discussion during this activity. A special AUA value for your patients: www.UrologyHealth.org is a joint AUA/AFUD patient education web site that provides accurate and unbiased information on urologic disease and conditions. It also provides information for patients and others wishing to locate urologists in their local areas. This site does not provide medical advice. The content and illustrations are for informational purposes only. This information is not intended to substitute for a consultation with a urologist. It is offered to educate the patient, and their families, in order for them to get the most out of office visits and consultations.

- 5. Commercial Support Acknowledgements AUA Office of Education thanks the companies and representatives who support continuing education of physicians with unrestricted educational grants, displays at educational meetings, and their expertise. This is a valuable resource to everyone. The AUA Office of Education salutes the following company for providing an educational grant in support of the Kidney Cancer: Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Management course at the 2008 Annual Meeting. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals The scientific programs and faculty are independently developed and finalized by the Chair of Education, the Director of Education and Scientific Program Director with no influence or input from these or any companies providing either an unrestricted educational grant or technical support. Comments or letters regarding this program and/or company involvement in an educational meeting may be addressed to: Jan Baum, M.A. Director of Education American Urological Association 1000 Corporate Boulevard Linthicum, MD 21090 (410) 689-3930

- 7. Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Management of Kidney Cancer W. Marston Linehan, M.D. Chief, Urologic Oncology Branch National Cancer Institute Bldg 10 Rm 1-5942 Bethesda, Maryland 20892-1107 Tel: (301) 496-6353 Fax: (301) 402-0922 Email: Email: WML@nih.gov Peter Pinto, M.D. Senior Investigator, Urologic Oncology Branch National Cancer Institute Bldg 10 Rm 2-5940 Bethesda, Maryland 20892-1107 Tel: (301) 496-6353 Fax: (301) 402-0922 Email : pintop@mail.nih.gov Jeffrey A. Sosman, M.D. Professor of Medicine (Hematology/Oncology) Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer 777 Preston Building Nashville, TN 27232-6307 Office (615) 343-7602 Email: jeff.sosman@Vanderbilt.Edu

- 8. RECENT ADVANCES IN DIAGNOSES AND MANAGEMENT OF KIDNEY CANCER Saturday, May 17, 2008 6:00PM - 8:00PM From To Speaker Topic 6:00 PM - 6:20 PM W. Marston Linehan, M.D. I. Molecular Genetics of Renal Carcinoma: Implications for the Urologic Surgeon II. Hereditary Forms of Renal Cancers 6:20 PM - 7:00 PM Peter A. Pinto, M.D. III. Techniques and Indications A) Laparoscopic Nephrectomy B) Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy IV. Robotic Assisted Nephrectomy and Partial Nephrectomy 7:00 PM - 7:40 PM Jeffrey A. Sosman, M.D. V. Role of Targeted Systemic Therapy In the Management of Advanced Clear Cell And Non-Clear Cell Kidney Cancer A) Sorafenib B) Sunitinib C) Bevacizumab D) Temsirolimus 7:40 PM - 8:00 PM W. Marston Linehan, M.D. VI. A) Management of Patients Who Present with Peter A. Pinto, M.D. Advanced Disease with Kidney In Place Jeffrey A. Sosman, M.D. B) Role of Adjuvant Therapy in the Management of Patients with High Risk Kidney Cancer 2

- 9. I. Introduction Kidney cancer affects over 39,000 Americans annually and it is estimated that nearly 13,000 will die of this disease in the United States each year. Patients who are found to have the disease when it is localized to the kidney can have up to a 95% 5 and 10 year survival rate. Patients who present to their urologic surgeon with locally advanced disease have up to a 65% chance of surviving 5 years. Those who present with advanced disease have an 18% 2 year survival rate.1,2 The advent of laparoscopic surgery has provided new and significantly less morbid surgical strategies for the management of patients with localized, locally advanced and even advanced renal carcinoma. There have been exciting advances in the development of new minimally invasive strategies for the management of patients with localized kidney cancer involving radio frequency ablation therapy as well as cryotherapy. Recent advances in immunologic and molecular targeted forms of therapy have provided new hope for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma.3,4 1. Molecular Genetics of Renal Carcinoma: Implications for the Urologic Surgeon (W. Marston Linehan, M.D.) Kidney cancer is not a single disease, it is made up of a number of different types of cancer that occur in the kidney; each with a different histology, having a different clinical course, responding differently to therapy and caused by different genes. Figure 1 Kidney cancer is made up of a number of different types of cancer, each with a different histology, with a different clinical course, responding differently to therapy and caused by different genes. From Linehan, et al.5 This section of the course will update you on current studies of the molecular genetics of sporadic and familial renal cancer, background on kidney cancer tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes, data for why we conclude that the von Hippel Lindau disease gene and the Met genes are critical genes for both hereditary and non-familial, sporadic kidney cancers, for how these genes fit the definitions of cancer genes and how these types of findings could lead to better methods for early diagnosis, prevention and, potentially, therapy of renal cancers will be presented. 3

- 10. 2. Tumor Suppressor Genes and Oncogenes A. Tumor Suppressor Genes The pioneering studies of Dr. Alfred Knudson led to the development of a hypothesis that the most basic aspect of cancer would involve what is called a tumor suppressor gene. Instead of cancer being the result of activation of a gene such as an oncogene, which drives the abnormal proliferation that we know of as cancer, Knudson hypothesized that, instead, cancer could be the result of inactivation of a gene, a so called tumor suppressor gene, whose normal function was to regulate or control cellular growth. We each have two copies of each gene, one maternal and the other paternal. If both copies of a tumor suppressor gene were inactivated (Knudson “two-hit” hypothesis) by either loss of DNA (DNA sequence deletion), or another mechanism such as mutation, transformation would result. Knudson hypothesized that if this were the case in a sporadic, non-hereditary cancer, and there were a hereditary variant of the same malignancy, that the same gene might be involved in the origin of both. This is the case in retinoblastoma, where both copies of the retinoblastoma gene are inactivated in both the sporadic and hereditary form of the disease. Abnormalities of tumor suppressor genes have been found in a number of solid human tumors, including breast, bladder and, as we shall see, kidney cancer. The VHL kidney cancer tumor suppressor gene, the gene for clear cell renal carcinoma, is a classic tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 3. B. Oncogene An oncogene is a “gain of function gene”; i.e., a gene in which a mutation of the gene results in activation of the gene, resulting in the unregulated growth that we know of as cancer. Often an oncogene may be “duplicated” in a cancer, resulting in three copies of the gene (instead of two copies). This is called trisomy. The c-Met oncogene, the gene for Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma (HPRC), is a classic oncogene located on chromosome 7. 4

- 11. II. Hereditary Forms of Renal Cancers Kidney cancer is like retinoblastoma and colon cancer in that there is both a sporadic and a familial form. Familial kidney cancer is far more prevalent than had been previously imagined. It is estimated that 5% of kidney cancer is familial (hereditary). There are four types of hereditary kidney cancer. The well described is clear cell renal cancer associated with von Hippel Lindau (VHL); there is a hereditary form of type 1 papillary renal carcinoma (HPRC); the third type is hereditary chromophobe renal carcinoma associated with Birt Hogg Dubé (BHD) and the fourth is a hereditary type of papillary type 2 renal carcinoma associated with Hereditary Leiomyomatosis Renal Carcinoma (HLRCC). Table 1 Inherited Forms of Renal Carcinoma 1. Von Hippel Lindau (VHL) Clear Cell RCC 2. Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma (HPRC) Papillary Type 1 RCC 3. Birt Hogg Dubé (BHD) Chromophobe RCC/Oncocytoma 4. Hereditary Leiomyomatosis RCC (HLRCC) Papillary Type 2 RCC These familial forms of kidney cancer are different from sporadic, non-familial kidney cancer in that they tend to be multifocal, bilateral and occur at a younger age, suggesting a genetic predisposition to develop these cancers. 1. Von Hippel Lindau (VHL) A. Renal Carcinoma Gene Localization Studies: Inherited Renal Cancer To identify the disease gene for clear cell kidney cancer the familial form of renal cell carcinoma associated with von Hippel Lindau (VHL) was studied. Von Hippel Lindau is an autosomal dominant hereditary cancer syndrome in which affected individuals are at risk to develop tumors in a number of organs, including the kidneys. VHL patients are at risk to develop multiple, bilateral renal carcinomas and cysts, cerebellar and spinal hemangioblastomas, pheochromocytomas, retinal angiomas, epididymal cystadenomas, pancreatic cysts and islet cell tumors and tumors in the inner ear, endolymphatic sac tumors. 5

- 12. Table 2 Clinical Features of VHL h Kidney tumors (clear cell RCC) h Adrenal tumors (pheochromocytoma) h Pancreatic tumors (islet tumors) h CNS tumors (hemangioblastoma) h Retinal tumors (angioma) h Endolymphatic sac tumors (inner ear) h Epididymal cystadenoma B. VHL: Clinical Evaluation Clinical evaluation of VHL patients involves MRI of the brain and spine (for CNS hemangioblastomas), abdominal CT and ultrasound (for evaluation of renal, adrenal and pancreatic manifestations of VHL), ophthalmologic evaluation (for evaluation for retinal hemangiomas), audiometric and ENT evaluation (to search for presence of ELST tumors), testicular ultrasound (to evaluate epididymal cystadenomas). Table 3 Clinical Evaluation-VHL • VHL gene germline mutation testing • MRI of the brain and spine • Abdominal CT and ultrasound • Ophthalmologic evaluation • Audiometric and ENT evaluation • Testicular Ultrasound • Metabolic evaluation (catechols) C. VHL: Surgical Management Surgical management of the renal manifestations of VHL patients involves nephron sparing surgery whenever possible. Patients with small renal tumors, generally under 2.5 cm, are often managed with expectant management. When the tumors reach 3 cm, surgery is often recommended. As it has been estimated that there can be up to 600 tumors per kidney in VHL patients, surgical resection of renal lesions is not considered “curative.” Rather, it is considered that surgical management will hopefully “set back the clock”; i.e. help prevent metastasis. Historically 35 to 45% of VHL patients have died of complications of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. The decision to recommend surgery must balance the risk of metastasis with the morbidity of surgery. This is often a complex issue in VHL patients with multisystem manifestations. When surgery is performed, thorough evaluation of the kidney with intraoperative ultrasound is considered a valuable adjunct to the surgical procedure. This allows 6

- 13. the surgeon to localize renal tumors and cysts and to perform as thorough and safe a procedure as possible. Renal Lesions in VHL Patient Microscopic VHL RCC Focus It is important that VHL patients undergo a complete screening and metabolic evaluation prior to a surgical procedure, to rule out such unsuspected manifestations as a CNS hemangioblastoma or pheochromocytoma. D. The VHL gene is on Chromosome 3 In order to identify the gene associated with VHL we evaluated affected and at risk individuals for VHL. DNA was extracted from blood of over 4,000 individuals. 450 patients were screened at the NIH for the presence of von Hippel Lindau. In order to localize this kidney cancer disease gene genetic linkage analysis was utilized, which narrowed the area of the VHL gene to a small region on chromosome 3, which is the same region where we showed abnormalities in tumor tissue from patients with non-familial, clear cell kidney cancer. Mutations of the VHL Gene in the Germline of VHL Patients From Chen et al.6 E. The VHL gene is the gene for sporadic, non-inherited clear cell RCC Mutations of the VHL gene is tumors from patients with sporadic, non- hereditary clear cell kidney cancer. From Gnarra, et al. 7 VHL mutations have been identified in a high percentage of tumors from patients with sporadic, clear cell renal carcinomas. VHL somatic mutations have been detected in the earliest, 7

- 14. localized clear cell tumors. No mutations have been found in papillary, chromophobe, collecting duct or other types of renal tumors. F. Molecular Targeting the VHL gene in clear cell kidney cancer It is hoped that understanding the pathways for the genes that cause kidney cancer will lead to the development of more effective forms of therapy for patients with this disease. The VHL clear cell kidney cancer gene was identified in 1993 and since that time an intensive effort has been underway to identify how damage to this gene leads to kidney cancer. The VHL gene product has been found to be important regulator of Hypoxia Inducible Factor (HIF). HIF is a transcription factor which regulates a number of downstream genes known to be important in cancer, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), erythropoietin, etc. Scientists are currently evaluating the role of small molecules that block this pathway as potential strategies for therapy. VHL Kidney Cancer Gene Pathway RCC Molecular targeting: anti-VEGF antibody. Adapted from Linehan, et al.5 The FDA recently approved three new agents, sunitinib, sorafenib and temsirolimus for the treatment of patients with advanced kidney cancer. Targeting VHL/HIF in Clear Cell RCC VHL HIF VEGF PDGF TGF-α VEGFR PDGFR EGFR Sunitinib Sunitinib The partial response rate in patients with advanced renal carcinoma treated with sunitinib has been reported to be 31% and there was an increase in progression free survival in patients treated with sunitinib versus interferon.8 The most commonly reported side effects with sunitinib involve diarrhea, skin discoloration, mouth irritation, weakness, and altered taste. Patients treated with sunitinib may also experience, high blood pressure, fatigue, bleeding, and swelling. 8

- 15. Targeting VHL/HIF in Clear Cell RCC VHL HIF VEGF PDGF TGF-α VEGFR PDGFR EGFR Raf Raf Sorafenib Sorafenib Sorafenib Sorafenib The partial response rate in patients with advanced renal carcinoma treated with sorafenib has been reported to be 10% and the progression free survival was 5.5 months versus 2.8 months for patients treated with placebo.9 Targeting VHL/HIF in Clear Cell RCC VHL HIF mTOR Temsirolimus VEGF PDGF TGF-α VEGFR PDGFR EGFR Temsirolimus (inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin-MTOR) Temsirolimus, the MTOR-inhibiting agent, has been found to have activity in patients with advanced, poor prognosis kidney cancer. In a recent report of a randomized three-arm phase 3 trial, temsirolimus was found to have an overall statistically significant survival benefit versus treatment with interferon alone (10.9 versus 7.3 months). This study confirmed MTOR as a valid target in kidney cancer and that temsirolimus monotherapy prolongs survival in patients with poor prognosis kidney cancer. 10 G. Adjuvant Treatment The role of agents such as sunitinib and sorafenib in the adjuvant setting are not known. To address this question, a randomized phase 3 trial involving 1332 patients, supported by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), the Cancer Trials Support Unit CTSU), the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG), the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) and the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC). In this trial, patients with T1B, T2 or T4 (N0-N2) will be randomized to receive one year of sunitinib, sorafenib or placebo after nephrectomy.11 Information about the trial can be found at the Kidney Cancer Association web site. 9

- 16. 2. Hereditary Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma: HPRC A. HPRC: Clinical Features Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma is a hereditary cancer syndrome in which affected individuals are at risk for the development of bilateral, multifocal, type 1 papillary renal carcinoma.12 HPRC patients are at risk for the development of up to 3,000 tumors per kidney, which are uniformly of type 1 papillary histologic type.13 Figure 2 Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma (HPRC) is a hereditary cancer syndrome where affected individuals are at risk for the development of bilateral, multifocal, type 1 papillary renal carcinoma. From Linehan, et al.5 Table 4 Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma (HPRC) h Clinical Features h Bilateral, multifocal papillary renal cell carcinoma h Type I papillary renal carcinoma h Clinical Evaluation – C-Met gene germline mutation testing – Abdominal CT and ultrasound 10

- 17. B. Met is the Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma gene The gene for type 1 papillary renal carcinoma associated with Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma is the Met proto-oncogene on chromosome 7.14,15 Met is a normal gene (a proto- oncogene) that codes for Met, the cell surface receptor for the ligand hepatocyte growth factor. Met becomes an oncogene when activating mutations occur in the tyrosine kinase domain of this gene in the germline of HPRC patients. A simple blood test is available to determine if the at- risk individual carries the germline Met mutation. Figure 3 Met, the cell surface receptor for the ligand, hepatocyte growth factor, is the gene for Hereditary Papillary Renal Carcinoma. Germline mutations of Met are found in affected individuals in HPRC kindreds. From Linehan, et al 5 11

- 18. 3. Birt Hogg Dubé (BHD): Chromophobe Kidney Cancer Birt Hogg Dubé is a hereditary syndrome in which affected individuals are at risk for the development of kidney cancer, cutaneous lesions and pulmonary cysts. Figure 4 Birt Hogg Dubé (BHD) is a hereditary cancer syndrome in which patients are at-risk for the development of cutaneous lesions (fibrofolliculoma), pulmonary cysts and kidney cancer. From Linehan et al.5 The kidney tumors can be chromophobe, hybrid/oncocytic, papillary or clear cell RCC.16 The BHD gene was recently identified on chromosome 1717 and a blood test is now available for determination of whether at-risk individuals are affected with BHD.18 Table 5 Clinical Features of Birt Hogg Dubé (BHD) h Cutaneous nodules (hair follicle tumors, fibrofolliculoma) on the face and neck h Pulmonary cysts h Renal tumors h Chromophobe RCC h Oncocytic hybrid RCC h Clear cell RCC h Oncocytoma 12

- 19. Figure 5 BHD associated kidney cancer can be chromophobe, hybrid/oncocytic RCC or oncocytoma. From Linehan, et al.5 Table 6 Clinical Evaluation-BHD • BHD gene germline mutation testing • Dermatologic evaluation-skin biopsy • Lung CT • Abdominal CT/ultrasound 13

- 20. 4. Hereditary Leiomyomatosis Renal Cell Carcinoma (HLRCC) A. HLRCC: Clinical Features Hereditary leiomyomatosis renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) is a hereditary cancer syndrome in which affected individuals are at risk for the development of cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas (fibroids) and an aggressive form of type 2 papillary kidney cancer.19 Figure 6 HLRCC is a hereditary cancer syndrome in which affected individuals are at-risk for the development of cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas and type 2 papillary renal carcinoma. From Linehan, et al.5 Table 7 Clinical Features of Hereditary Leiomyomatosis Renal Cell Carcinoma (HLRCC) h Cutaneous nodules (leiomyomas) h Uterine leiomyoma (fibroids) h Uterine leiomyosarcoma h Renal tumor (type 2 papillary RCC) h Often solitary h Aggressive, early to metastasize B. Fumarate Hydratase (FH) is the gene for HLRCC The Krebs cycle enzyme, fumarate hydratase (FH) is the gene for the hereditary form of Type II papillary renal carcinoma associated with Hereditary Leiomyomatosis Renal Carcinoma (HLRCC) and there is a blood test available to determine whether or not a patient is affected with HLRCC.20 These tumors can be very aggressive21 and partial nephrectomy is often not recommended for these patients. Early intervention with nephrectomy is recommended as these aggressive tumors may spread early. 14

- 21. Table 8 Clinical Evaluation-HLRCC • Fumarate hydratase (FH) gene germline mutation testing • Dermatologic evaluation-skin biopsy • Abdominal CT/ultrasound • Pelvic CT/uterine ultrasound 5. Familial Renal Carcinoma (FRC) Recently scientists in Iceland have performed studies suggesting that genetic susceptibility may be a major component in the development of ordinary, “sporadic” renal carcinoma. In their initial study, 68% of individuals in Iceland who had kidney cancer had up to a second degree relative (a second cousin) with kidney cancer. This work suggests that it is important to ask all patients with renal carcinoma whether any other family member also was affected with renal carcinoma. Urologic surgeons at the NCI are currently studying families in which multiple members are affected with kidney cancer (FRC) in order to identify the genetic basis of this form of kidney cancer.22 Figure 7 Studies have shown that there may be a strong hereditary component to “sporadic” kidney cancers. Investigators are currently intensively studying families in which more than one family member has kidney cancer in order to determine the gene(s) for familial renal carcinoma. From Linehan, et al.5 15

- 22. III. Techniques and Indications (Peter Pinto, M.D.) A) Laparoscopic Nephrectomy Surgical Technique: Transperitoneal Approach Positioning The following will describe the operative technique for a transperitoneal left laparoscopic nephrectomy. The patient undergoes general endotracheal anesthesia, prophylactic antibiotics and placement of an orogastric tube and urinary catheter. While supine the lower midline incision is marked with an indelible pen. This is done prior to positioning to allow the incision for possible specimen extraction to be symmetric in reference to the midline. This is difficult to judge after the patient is positioned. The patient is then placed in a modified left flank position with a bump under their left side. The right arm is tucked and the left arm is folded over cushions across the chest. (Picture 1) Picture 1) Positioning for transperitoneal left laparoscopic renal surgery. From Pinto, et al.23 All pressure points are checked and padded. The patient is secured to the table with 3 inch wide silk tape. In order to confirm that the patient is adequately secured, the table is maximally tilted prior to draping. Port Placement The operating table is returned to a neutral position and the patient is prepped and draped in the standard fashion. The surgeon and assistant stand on the patient’s right side and the scrub nurse on the left side by the legs. In cases where a robotic camera holder is used, it is secured to the table at the level of the patient’s right shoulder prior to draping. With the aid of a Veress needle, pneumoperitoneum is established at a pressure of 20 mmHg. Four trocars are subsequently placed: a 10mm periumbilical port for the camera, a 12mm port in the left midaxillary line at the level of the umbilicus, a 12mm port in the midline of the premarked pfannensteil incision, and a 5mm trocar in the midline, halfway between the umbilicus and 16

- 23. xyphoid. (Picture 2) In obese patients, the port placement is altered slightly. In these cases, the ports are shifted laterally, with the camera port at the level of the umbilicus, but lateral to the rectus muscle. (Figure 1) Picture 2) Port placement for left laparoscopic nephrectomy/partial nephrectomy. Lower midline port can be extended for specimen retrieval. Figure 1) Port placement shifted laterally for obese patient. From Williams et al.24 A visualizing trocar is used to place the first port, allowing the remaining three to be placed under vision. Even in the setting of previous abdominal surgery, initial entry with a veress and visualizing trocar has been shown to be safe. ( J Urol 170, 61–63, July 2003) All trocars are secured to the skin with suture to avoid inadvertent removal during surgery. 17

- 24. Procedure The table is then tilted maximally to the right to help the bowel fall medially. This can be facilitated by an assistant using a paddle retractor through the low midline port. The retroperitoneal space is entered by incising the line of Toldt sharply from the spleen to the iliac vessels. (Figure 2) Figure 2) Entering the retroperitoneal space As the descending colon is reflected medially care must be taken to develop the plane between the mesocolon and anterior gerota’s fascia. If not, a common mistake is to dissect lateral to the kidney. This divides the renal attachments laterally and makes future hilar dissection more difficult. In order to obtain proper exposure to the renal hilum and especially for upper pole tumors, the splenophrenic ligament must be incised. Take care to avoid inadvertent injury to the stomach and diaphragm as the spleen is being mobilized. Once completely mobilized, the spleen, tail of pancreas and splenic flexure will fall medially out of the operative field. Upper pole dissection is then carried out. The lienorenal ligaments are divided sharply in order to avoid inadvertent splenic lacerations. This dissection is carried out toward the renal hilum in order to separate the adrenal gland and expose the adrenal vein as it enter the renal vein. In cases where the tumor location does not necessitate taking the adrenal gland, the renal vein may be transected lateral, preserving the adrenal vein’s entry into the renal vein. Alternatively, the adrenal vein can be clipped and divided. (Figure 3) 18

- 25. Figure 3) Upper pole mobilization when needed With the upper pole of the kidney mobilized, attention is turned to the lower pole of the kidney, ureter, gonadal and renal hilum. Dividing the colorenal ligaments allows the colon to fall medially and exposes the lower pole, gonadal vessels and ureter. (Figure 4) Figure 4) Lower pole, ureteral and gonadal dissection A plane is developed between the psoas muscle and the gonadal/ureteral packet. If the ureter is difficult to identify, or obscured by a large lower pole mass, the dissection can be started distally at the level of the iliac vessels and continued proximally to the renal vein. At the level of the renal hilum lumbar vessels are ligated and divided as necessary. The neuro-lymphatic and fibrofatty tissue surrounding the renal artery and vein is ligated and divided isolating the artery down to its take off from the aorta. This dissection also allows for a hilar lymphadenectomy to be performed if indicated. The renal artery and vein can be controlled with titanium or polymer clips (leaving 3 on the patient side) or an endoscopic linear cutter stapler with a vascular staple load (Figure 5). 19

- 26. Figure 5) Ligation of the renal vessels With the vessels divided, the ureter is ligated and the remaining lateral, posterior and superior attachments are freed with cauterized scissors. If intact specimen extraction is to be performed, the lower midline trocar is then exchanged for an entrapment sac device (15mm Endo Catch II, US Surgical, Norwalk, CT). The specimen can then be placed into the deployed entrapment sac and delivered through a low midline incision which incorporates the lower midline trocar. The extraction incision is then closed and pneumoperitoneum is re-established to ensure that adequate hemostasis was obtained. This is done at a pressure of 5mmHg to reveal bleeding that might be present at normal insufflation pressures. Alternatively, the specimen can be morcellated. In these cases the specimen must be placed in an impermeable entrapment sac (Lapsac® Cook, Bloomington, IN) prior to morcellation. The 12mm trocar sites are then closed with the aid of a needle-point suture passer after the pneumoperitoneum has been evacuated. Indications for laparoscopic radical nephrectomy include organ confined tumors (stage Tl or T2) not amenable to nephron-sparing surgery. Some investigators have demonstrated that even large masses (12cm) can be removed laparoscopically. Tumors spreading beyond Gerota's fascia or involving the renal vein are technically challenging, but have been performed. Laparoscopy has also provided a benefit to patients in the setting of metastatic disease. Surgical Technique: Retroperitoneal Approach Positioning The patient is placed on the operating table in the standard flank position with the side of pathology facing up. The top arm is draped over a padded Mayo stand or multiple pillows. An axillary roll is placed. The bottom leg is flexed and bent while the top leg is straight. The kidney rest is elevated and the table is flexed in order to maximize the working space between the ribs and iliac crest (Picture 3). 20

- 27. Picture 3) The patient is placed in a full flank position with the kidney rest elevated and the table flexed. This increases the distance between the costal margin and iliac crest, thus maximizing the working space. The skin between the iliac crest and the ribs should be taut on palpation. All pressure points are padded and the patient is then secured to the table with tape at the shoulders, hips, and legs. The table is rotated left and right to make sure the patient does not shift during the procedure. The surgeon and camera assistant are positioned facing the patient's back. The scrub nurse stands on the opposite side at the end of the table. (Fig 6) Fig 6) Operating room setup for laparoscopic retroperitoneal renal surgery. From Pinto et al.25 21

- 28. Two monitors are used to provide all personnel with an unobstructed view. Alternatively, the camera assistant can be replaced by a mechanical or robotic arm which can be fixed to the operating table to hold the camera. The robotic arm is controlled by the surgeon through voice commands, a hand control or a foot pedal. Access and Port Placement Three trocars are positioned in the anterior, mid, and posterior axillary lines.(Picture 4) Picture 4) Trocar placement. The laparoscope is positioned in the mid-axillary line. A 12-mm port is placed in the posterior axillary line. A 5-mm port is placed in the anterior axillary line. Initial entry into the retroperitoneal space is established off the tip of the 12th rib via the open Hassan technique. A 1.5 cm transverse incision is made just anterior and inferior to the tip of the 12th rib. The incision is carried down sharply through the posterior thoracolumbar fascia, flank muscles and anterior thoracolumbar fascia. Upon entering the retroperitoneal space, the index finger is used to sweep the peritoneum anteriorly and medially, developing a space between the psoas muscle anteriorly and Gerota’s fascia posteriorly. (Fig 7) 22

- 29. Fig 7) The surgeon's finger is used to start the retroperitoneal dissection. A space behind the kidney is created to place the balloon dissector. See Pinto et al.25 The retroperitoneal space can then be created with balloon dissection (Fig 8A) and the balloon tipped 10mm trocar (Fig 8B) provides a seal to establish the pneumoretropertioneum. A) B) Fig 8 A) The working space is created by balloon dissection. The kidney and peritoneum are displaced anteriorly exposing the renal hilum. B) Blunt-tipped trocar. The collar on the port slides down against the balloon tip to prevent loss of pneumoretroperitoneum. See Pinto et al.25 Alternatively, retroperitoneal access can be obtained directly with a 12 mm laparoscopic visualizing trocar. Once the characteristic fat of the retroperitoneum is seen, insufflation is begun. The laparoscope is used to bluntly develop the working space. Surgical Technique Renal dissection is carried out as was described previously, but without the need to manipulate the peritoneal organs. The psoas muscle and ureter are the initial structures for orientation, since the intraperitoneal structures are not seen. Maintaining orientation is important throughout the procedure. This helps identify landmarks such as the psoas muscle, peritoneal 23

- 30. reflection, ureter, gonadal vein, and pulsations of the renal artery. Initial dissection is carried out posteriorly to isolate the ureter and mobilize the lower pole. The peritoneal attachments anterior to the kidney are not divided in order to prevent the kidney from falling into the working space. Blunt dissection along the ureter reveals the gonadal vein. Theses structures are traced cephalad to the renal hilum. Dissection along the aorta or vena cava will quickly bring the renal vessels into view. The renal artery is encountered first as it lies posterior to the vein. Hilar ligation is performed as was described in the transperitoneal approach. Once the vessels have been controlled, the anterior surface of the kidney is mobilized from its peritoneal attachments. Care is taken not to enter the peritoneum and injure the adjacent bowel and mesentery. Post-Operative Management Prior to extubation the orogastric tube is removed. After routine observation in a post anesthesia care unit, the patients are transferred to a non-monitored floor bed. In the morning of the first post operative day, the urinary catheter is removed, routine blood work is performed, ambulation is encouraged and oral liquids are started. The diet is then advanced as tolerated throughout the day. Routine discharge is in the morning of post-operative day # 2 if blood work and vital signs are stable, the patient is able to ambulate and tolerate oral diet. 24

- 31. III. Techniques and Indications: B) Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy Surgical Technique: Transperitoneal / Retroperitoneal Approach Positioning and Port Placement Same as for laparoscopic nephrectomy. Additional instruments needed for laparoscopic partial nephrectomy include: laparoscopic vascular clamps (Picture 5- bulldogs, Picture 6- Statinksy), ultrasound with a laparoscopic transducer and topical hemostatic sealant. Picture 5) Laparoscopic bulldog clamps Picture 6) Laparoscopic Statinsky clamp Procedure When the renal mass is abutting the collecting system, and entry into a calyx is expected, cystoscopy and placement of an open ended 5 French ureteral catheter is performed before positioning. This aids in reconstructing the collecting system by retrograde injection of dilute methylene blue. As in open surgery, dissection of the kidney is performed leaving a “cap”of fat overlying the renal tumor. Intraoperative ultrasound aids in determining the tumor’s depth and also to rule out any additional tumors. 25

- 32. Exophytic masses that are attached by a narrow base and peripherally located can be excised without the need for vascular occlusion. The capsule around the tumor is scored with cautery, and the mass is removed with the aid of laparoscopic scissors or an ultrasonic scalpel. Hemostasis is obtained with the aid of an argon beam coagulator and hemostatic sealants. Large, more broad-based or deeper tumors require interruption of renal blood flow. Prior to clamping the renal hilum, a brisk diuresis is initiated with the use intravenous fluids and osmotic diuretics. Mannitol (25 grams) is given when the surgeon begins to free up the renal hilum allowing for increased perfusion of the renal parenchyma along with protection from free radical deposition. The capsule around the mass is scored, and a laparoscopic bulldog clamp is placed on the renal artery. Alternatively, a laparoscopic Statinsky vascular clamp can be used, but this requires the placement of an additional trocar. Hilar clamping is performed to allow for a bloodless field and therefore better visualization when resecting the tumor. The tumor is excised with cold scissors to allow pathological assessment of the tumor’s margins. The tumor is excised ensuring a rim of normal parenchyma around it. Any suspicious areas in the renal bed can be biopsied and sent for frozen section analysis. Retrograde instillation of methylene blue via the ureteral catheter ensues that the collecting system has not been entered. If it has, repair is performed with 2-O polyglactin suture. Open vessels seen in the renal bed are suture ligated with 2-O polyglactin suture. A gelatin matrix hemostatic sealant is applied and the kidney is reconstructed by reapproximating the renal defect over surgicel bolsters (Picture 7) using O polyglactin sutures through the renal capsule. Picture 7) Surgicel pledgets, approximately 1 cm wide and 4 cm long, are prepared prior to tumor excision. The clamps on the renal vessels are removed and the kidney is observed to confirm it is being well perfused and there is no active bleeding. Prior to exiting the abdomen, a closed suction drain is left in the retroperitoneum behind the kidney. Cold ischemia is technically feasible laparoscopically, but not practical. Therefore when operating under the time constraints of warm ischemia, it is important to be expeditious in your approach to resection and reconstruction of the kidney. Indications for laparoscopic partial nephrectomy are as described for the open procedure. Although initially indicated for tumors involving a solitary kidney or bilateral disease, nephron- sparing surgery is now performed for tumors smaller than 4cm in the presence of a normal contralateral kidney. 26

- 33. IV. Techniques and Indications: Robotic Assisted Nephrectomy and Partial Nephrectomy Nephron sparing surgery for complex renal tumors, such as multiple, endophytic, or hilar tumors, may further preclude a laparoscopic approach for most urologists and may pose challenges for even experienced laparoscopic surgeons. A renal mass with tumor thrombus may require vascular suturing, which is also challenging for laparoscopic techniques. It is in these cases that robotic renal surgery may be of assistance. Potential advantages include 3-dimensional stereoscopic vision, articulating instruments, and scaled-down movements reducing tremor. The articulating instruments and increased freedom of movement may also allow the surgeon to replicate well established open surgical maneuvers more readily. This technique emulates both open and laparoscopic techniques of renal cancer surgery. (Rogers et al. 2008) Surgical Technique: Transperitoneal Approach Positioning, Ports, and Docking: After intubation, orogastric tube placement and bladder catheterization, the patient is positioned in modified lateral position. Full flank position may also be used. Following abdominal insufflation with a Veress needle. Ports are placed as demonstrated in Picture 8. A 12mm periumbilical port is placed for the camera. Two robotic instrument ports are placed approximately 8 cm from the camera in a wide “V” configuration centered on the renal tumor. These ports may be shifted laterally and/or superiorly for patients with a large body habitus or upper pole tumor location. A 12 mm assistant port is placed inferior to the camera port. An optional 5mm assistant port may be placed above the camera port if needed. For docking (as seen in Picture 9), the robot is brought in posteriorly at approximately a 20 degree angle toward the head of the patient. Picture 8) Port placement for left sided robotic renal surgery 27

- 34. Picture 9) daVinci robot is docked against the patient’s back at approximately a 20 degree angle toward the head of the patient. Bowel Mobilization: A zero degree lens is used initially, but a 30 degree downward lens may also be utilized as needed. Robotic instruments used include a Bipolar Maryland forceps, monopolar cautery scissors, and needle drivers. The peritoneum is incised sharply along the Line of Toldt and the bowel is mobilized medially using sharp and blunt dissection, developing the plane between the anterior Gerota’s fascia and the posterior mesocolon. The bedside assistant maintains medial counter-traction. Dissection is continued along the upper pole of the kidney to mobilize the spleen or liver. We utilize robotic assistance from the beginning of bowel mobilization unlike some reports of a “hybrid technique”, initially utilizing conventional laparoscopy to reflect the bowel. Anatomical Landmarks and Hilar Dissection: Continued medial reflection of the bowel allows for exposure of the gonadal vessels and the ureter. These structures are retracted anteriorly, exposing the underlying psoas muscle. Care is taken not to strip the fascia from the psoas muscle. Dissection then proceeds towards the renal hilum. The Maryland bipolar forceps are used to place the kidney on stretch and the renal hilar vessels are dissected to allow access for clamp placement. Lateral renal attachments are left in place to aid in countertraction. Venous branches can be ligated as needed for exposure Ultrasound and Tumor Exposure: A laparoscopic ultrasound probe is used to map the location and size of renal tumor(s) and to confirm resection margins and depth during partial nephrectomy. Gerota’s fascia is opened and the fat is cleaned off the renal capsule to expose the tumor(s). The use of color Doppler may be used to identify adjacent vessels. The margin of resection is scored 28

- 35. circumferentially using monopolar cautery. In cases of nephrectomy and tumor thrombectomy, it is used to determine the extent of tumor thrombus. Hilar Clamping, Tumor Excision and Renal Reconstruction during Partial Nephrectomy: For tumors that are endophytic or adjacent to the renal hilum, resection is done under warm ischemia. The assistant clamps the renal hilar vessel(s) using laparoscopic bulldog clamp(s) through the primary 12mm assistant port. Mannitol (12.5 gm) may be administered intravenously prior to clamping. The tumor is resected along the previously scored margin using cold resection with the robotic monopolar scissors. The Maryland bipolar forceps are used to manipulate the tumor for exposure and to aid in dissection. The assistant uses suction to expose and maintain visualization of the resection plane of the tumor. After excision, the tumor can be placed beside the kidney or on top of the liver for later retrieval. If the status of the surgical margin is in question, a biopsy and frozen section analysis may be performed. Hemostasis is achieved using a combination of cautery, hemostatic agents, and suturing. A pre-placed ureteral catheter may be used to inject methylene blue to identify entry into the collecting system. The robotic instruments are exchanged for needle drivers. A 3-0 Vicryl suture on an RB-1 needle is used to achieve hemostasis and repair any previously identified entry into the collecting system (a SH needle may also be used). Sutures may be secured with either absorbable suture clips or by tying knots. Renal parenchymal defects are approximated over surgicel bolsters using 2-0 Vicryl sutures on an SH needle (a 0-Vicry suture on a CT-1 needle may also be used). A hemostatic agent is applied. Preplacing surgicel bolsters and sutures in the abdomen may reduce warm ischemia time during earlier experience. The kidney is placed back on stretch using the robotic needle driver and the hilar clamp is removed by the assistant. Hemostasis is confirmed. A pre-placed lap pad may be used to apply pressure to the resection site. The specimen is placed in a retrieval bag and removed through the primary assistant 12 mm port, enlarging the port site if needed. Gerota’s fascia is approximated over the defect using a running 3-0 Vicryl suture on an SH needle. A drain is placed in the perinephric space. 26-54 29

- 36. V. Role of Targeted Systemic Therapy in Management of Advanced Clear Cell and non-Clear Cell Kidney Cancer (Jeffrey A. Sosman, M.D.) Introduction Therapy of advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) has gone through a major evolution over the past few years. Previously, patients with RCC were considered for high dose Interleukin-2 therapy, if young and healthy and IFN-alpha for the less robust or elderly patient. A relatively small subset of patients did benefit from cytokine therapy, but far too few to effect median progression-free (PFS) or overall survival (OS)55,56. The great majority of patients only suffered the toxicity of treatment. This all began to change following the remarkable work of Drs. Kaelin, Maxwell, Linehan and others who helped define the role of the VHL gene and the consequence of loss of its function.57 The generation of an antibody to the vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF (anti-VEGF; Bevacizumab) molecule provided an initial tool to interrupt the downstream effects of VHL (Von Hippel Lindau) loss. The stabilization of the HIF-1a and HIF-2a molecules with the subsequent over expression of VEGF, PDGF, EGFR, CAIX, EPO, Glut1 etc was key to the malignant phenotype of clear cell RCC. This is a critical pathway not simply in genetic syndromes with Von Hippel Lindau, but in at least the majority of patients with sporadic clear cell RCC. In the initial report by Yang et al., anti-VEGF was shown to increase PFS >2 fold in a cytokine (IL-2) refractory population even though its objective response rate was only 10%.58 However, it was clear that even those without objective clinical responses had a far different clinical course than those on placebo with many having prolonged stable disease or small degrees of regression not meeting the 30% RECIST threshold of an objective response. A reassessment of meaningful clinical responses needed to be performed the first time there may have been convincing data that stable disease was an indication of benefit in RCC. In the interim, a number of multi- targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) that targeted the VEGFR2 tyrosine kinase as well as a variety of other receptor signaling pathways, have been evaluated and some approved for therapy of advanced RCC. These orally administered drugs were also able to inhibit other receptors including VEGFR1, VEGFR3, PDGF, c-kit, and RAF to name a few. The initial two agents receiving the most attention and most rapidly approved by the FDA were BAY43-9006 (Sorafenib) Nexavar and SU011248 (Sunitinib) Sutent.59 While their spectrum of kinase targets was overlapping, there were some key differences. Sorafenib inhibited RAF, while Sunitinib was a more potent and effective inhibitor of VEGFR2. (See Table 1) 30

- 37. Table 1: Phase II/III Trials of Targeted Agents in Untreated RCC patients Phase Pt Response Median Median Drug of Risk factors Nephrectomy Number Rate PFS OS Study 375 Favorable(34%) 39% 11 mos NA Sunitinib vs IFN III 90% 375 Intermediate(56%) 8% 5.1 mos NA Bevacizumab + 327 Favorable (28%) 31% 10.2mos NA III 100% IFN vs IFN 322 Intermediate(56%) 12% 5.4 mos NA Temsirolimus 209 8.6% 5.5mos 10.9mo Poor Prognosis Temsirolimus+IFN III 210 67% 8.1% 4.7mos 8.4 mo (74% MSKCC) Vs IFN 207 4.8% 3.1mos 7.3 mo Sorafenib 97 Favorable NA(68%)* 5.7mos NA II 95%/98% Vs IFN 92 Intermediate NA(39%)* 5.6mos NA Number in parenthesis represents % of patients with some degree of tumor shrinkage, not an objective response rate A) Sorafenib Initially, Sorafenib demonstrated prolonged progression-free survival in cytokine refractory patients in a phase II randomized trial where stable disease patients at 12 weeks were randomized to continue Sorafenib or switched to placebo (randomized discontinuation).59 Those patients having switched to placebo had a significantly less PFS than those on Sorafenib, when the placebo patients who progressed were rechallenged with Sorafenib, stable disease could be re-established. This was confirmed and proven in a large phase III trial of Sorafenib versus placebo in cytokine-refractory patients where again as in the phase II trial there was a doubling in progression-free survival from 2.8 to 5.5 months9. Unfortunately this study was then unblinded (per recommendations of the FDA) and overall survival results were confounded by the significant cross-over of patients from placebo to Sorafenib. It is worth pointing out that in both of these studies the objective response rate of Sorafenib was < 10% while many patients had smaller degrees of regression and prolonged stable disease. Later after its approval a relatively small, 189 patient, randomized phase II trial of Sorafenib or IFN in therapy-naïve patients was conducted. Surprisingly, there was no advantage to the Sorafenib arm.60 This was unexpected based on the second line results with Sorafenib in cytokine-refractory patients. While a low objective response rate could have been expected, the lack of any improvement in patients’ PFS with a median of 5.7 months, was a surprise. The trial also examined the effect of cross over to Sorafenib and dose escalation of Sorafenib in patients who progressed on their initial therapy. Patients progressing on IFN, could receive Sorafenib at standard doses of 400mg BID. This group of patients did exhibit some stabilization of their disease for 5.7 months and some degree of tumor shrinkage in 75% of patients. Those who progressed on Sorafenib could be dose escalated to 600mg BID and among these 44 patients, a 4.1 months median PFS and tumor shrinkage in 44% were observed. For all practical purposes, this large randomized phase II trial signaled the end of Sorafenib as a front line therapy in the 31

- 38. majority of patients. Larger, single agent, upfront trials with Sorafenib at standard doses, are unlikely to be explored further. B) Sunitinib The pathway to Sunitinib approval was quite different. Initial phase II studies did demonstrate a high response rate of 35-45% in cytokine-refractory patients, as well as prolonged progression-free survival. Following this result, Sunitinib was directly compared to IFN-alpha in therapy naïve patients. This large 750 patient trial demonstrated a remarkable objective response rate for Sunitinib that remained very high at 40%, while IFN's response rate was <10%8. Furthermore, the median progression-free survival was 11 months, more than double that of IFNα. The difference in overall survival did not meet significance due to the lack of events at the time of the analysis. Again the survival analysis is confounded by patient crossover from IFN to Sunitinib as allowed in the protocol once Sunitinib was approved by the FDA. C) Bevacizumab Following the approval of both MTKI, the results of several phase III trials featuring Bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) have been reported. In a large study now published in Lancet by Escudier, et al., IFN alone was compared to IFN with anti-VEGF in a population of therapy- naïve RCC patients.61 The results showed a striking improvement in response rate (31% vs 7%) and progression-free survival (10.2 mos vs 5.4 mos). The response rate was better than seen in both the initial Yang trial in cytokine refractory patients (10%) and the 13% in the randomized phase II trial of anti-VEGF +/- erlotinib (EGFR TKI). It is possible that the addition of IFNα to anti-VEGF led to a better response rate and improved the progression-free survival of anti- VEGF. But there are no more definitive results to either support or counter this argument. Finally, limited release results from a trial conducted by CALGB show there were further supporting data to the benefit of Bevacizumab plus IFN. The trial represented another phase III trial of IFN +/- anti-VEGF. The combined arm (anti-VEGF + IFN) demonstrated an improved response rate and progression-free survival compared to IFN alone. Final results are still pending. Issues with phase III trials in front line therapy When reviewing the important trials with Sorafenib, Sunitinib, and Bevacizumab, there are several important issues needing to be addressed. First, patients on all of these studies were either intermediate or low-risk based on the MSKCC criteria62. They had 0-2 of (anemia, hypercalcemia, high LDH, lower performance status (<70% Karnofsky criteria) or either within 1 year of diagnosis of RCC or without nephrectomy) the five criteria. Three or more of these criteria were indicative of poor prognosis. In previously evaluated patients at MSKCC, this criteria could separate patients with a 20 month median (low risk, favorable prognosis) overall survival to as low as a 4 month median survival for those high risk (poor prognosis) patients. The entry criteria for all of the above studies also required clear cell histology. All patients on the Bevacizumab plus IFN trial had nephrectomy (as per entry criteria), while over 90% had prior resection of their primary on the Sunitinib trial. There were a small number of poor prognosis patients entered on both trials, 6% on the Sunitinib trial and 8% on the Bevacizumab + IFN trial. Both the front and second line trials with Sorafenib enrolled patients with intermediate to low risk and nearly 90% had nephrectomy. The results in the poor 32

- 39. prognostic patients were dismal but PFS may have been improved from 1.2 months to 3.7 months in those receiving Sunitinib. Not even this small effect was seen in the Bevacizumab+ IFN trial where poor prognosis patients had a 2.1-2.2 median progression free survival regardless which arm they were enrolled on. D) Temsirolimus In phase I and II clinical trials, RCC patients appeared to derive a benefit of CCI-779, Temsirolimus, even though the response rates were less than 10%. Patients improved with less bone pain, improved appetite and weight gain. Temsirolimus is a mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor. mTOR is downstream from PI-3/Kinase/ Akt. It represents a pathway that can modulate protein synthesis (translation) including that of HIF-1a and HIF-2a. The phase II trial demonstrated that patients with poor prognostic factors had the greatest benefit. Benefit was based on a major extension in progression-free and overall survival in the poor prognosis group.63 Overall survival was much better than expected for this poor prognosis patient group. This led to a phase III trial comparing Temsirolimus versus IFN in poor prognostic patients (3 or more of 5 criteria in MSKCC). The trial did get slightly modified to increase poor accrual by adding one more poor prognostic factor, multiple disease sites (by organ involvement). Patients needed 3 or more of the 6 risk factors for entry. There were no restrictions on histology and requirements for nephrectomy. About 20% had non-clear cell histology and about 33% had their primary in place and were enrolled within their first year of diagnosis. The trial was an ambitious effort in a poor prognostic group of patients who in the past would likely not have been treated with cytokines due to their overall performance status. The trial included 3 arms; one with IFN alone; one with Temsirolimus; and the other a combination of both IFNa plus Temsirolimus 64. The doses of Temsirolimus were attenuated to allow concomitant IFNa therapy. The trial’s primary endpoint was overall survival, with progression-free survival only a secondary endpoint. Overall survival was increased from a median of 7.3 to 10.9 months with an overall hazard ratio of .73 and the p value=0.0069. PFS was improved in both the Temsirolimus arm and the IFN plus Temsirolimus arm, but those in the combined arm did not get any improvement in overall survival. This may have to do to the extensive dose modification of when IFN and Temsirolimus were given together. This result clearly established Temsirolimus as the standard therapy for poor prognostic patients. Overall response rates in all three arms were under 10%, further evidence that objective responses were a poor indicator of treatment benefit from drugs in RCC. Several additional analyses were done retrospectively on pre-treatment patient characteristics and clinical outcome. For those 74% of the overall enrollment who did qualify under the MSKCC model as a poor prognostic group (3 or more of 5 MSKCC criteria) the benefit from Temsirolimus was most prominent. Most of the benefit was apparently concentrated within this group of patients. Furthermore, about 20% of patients had histology of their tumor different from the typical clear cell. Papillary renal cancer makes up the bulk of these non-clear cell cancers. Others include chromophobe and sarcomatoid (high grade IV) that make up a small number of cases. In those patients with non-clear cell histology the benefit was especially prominent as is described below in non-clear cell RCC. This was unique to this trial of Temsirolimus since the other upfront trials excluded these patients and were restricted to clear cell RCC alone. 33

- 40. Toxicities from the targeted agents (See Table 2) In addition to overall survival, progression-free survival, and objective response rate, toxicity, and patient tolerance is of critical importance when considering treatment with this class of agents. This is especially true, since the nature of these agents is to continue their administration indefinitely or until progression. Complete responses are very rare and much of therapy is administered with the intent to maintain disease control. Both Sunitinib and Sorafenib have the most overlapping spectrum of toxicities as might be expected based on the targets of their action. Table 2: Toxicities from Targeted Agents Toxicities HTN Proteinuria Vascular Stomatitis HFS Rash Diarrhea Fatigue Complications Sunitinib X X X x X X Sorafenib X x X X X X Temsirolimus x X X Bevacizumab X X X X Common and significant problem x Less common and/or infrequent problem Sunitinib toxicity Sunitinib can cause fatigue, hypertension, a functional (symptomatic with minimal findings on examination) stomatitis, diarrhea, and some hand-foot syndrome. Most common grade 3 or 4 toxicities have been due to fatigue and hypertension, though hypertension in general can be well controlled with medications. At times multiple anti-hypertensive agents are required for adequate blood pressure control. Hypothyroidism is becoming more appreciated as a frequently associated side effect. Thyroid functions should be followed throughout treatment. Sometimes the fatigue from Sunitinib is due to thyroid dysfunction and this can be easily addressed with hormone replacement. A less frequent but increasingly recognized toxicity is a decline in cardiac ejection-fraction. While declines below normal range or greater than 10% of baseline are relatively common at 10-15%, symptoms of congestive heart failure is seen in less than 5% of patients. Obtaining baseline ejection fraction and subsequent follow-up cardiac evaluations are now recommended even in the absence of symptoms. Sorafenib toxicity Sorafenib toxicities include many of those seen with Sunitinib but there is a slight but recognizable change in the spectrum of them. Hypertension is common as with Sunitinib, but fatigue is infrequently a dose limiting toxicity. Diarrhea is experienced in up to 40% of patients but is grade 3 or 4 in only several percent. Most bothersome has been the hand foot syndrome that is observed in up to 30% of patients. While severe desquamation of the hands and feet is uncommon, symptomatic callus formation with neuropathic pain is frequently observed. Patients can have trouble with walking and use of their hands. This toxicity is readily reversible upon suspending drug administration, but if the symptoms worsen while drug continues to be given then recovery can be quite slow. Sorafenib can also induce a number of different rashes from a diffuse macular, papular, pruritic rash to a localized acneform rash similar to that associated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors or antibodies. It can also cause multiple furuncles and 34

- 41. carbuncles in and around the axillas or the inguinal regions. These can become secondarily infected and required drainage and antibiotics. Bevacizumab toxicity Bevacizumab is very well tolerated on a daily basis. Minor fatigue and myalgias can be associated with intravenous administration for 24-48 hours afterwards. Patients frequently experience hypertension and proteinuria. Blood pressure control is important since lack of control can lead to hypertensive crisis. Proteinuria must be monitored closely and in general is very reversible. Recommendations have become more lax in terms of the threshold for proteinuria in deciding to hold Bevacizumab. At the present time, 3.5 gm of protein in a 24 hour urine is the limit for continuing Bevacizumab dosing. Otherwise the dose is held until protein in urine has dropped below the threshold. Bevacizumab is generally safe and well tolerated. It must be recognized that Bevacizumab can significantly slow wound healing and even lead to wound dehiscence. This must be considered around procedure and any major surgery. In general Bevacizumab should be held two weeks prior to surgery and at least 4 weeks following surgery to allow healing to take place optimally. However there are much more infrequent toxicities of a very serious nature. These include vascular events, especially arterial thrombotic and venous thromboembolic , hemorrhage, multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with poorly controlled hypertension, gastrointestinal perforation, and fistula formation. Temsirolimus toxicity Finally, Temsirolimus is tolerated quite well. Some degree of asthenia (fatigue) is relatively common. However, this can be difficult to attribute to either disease or therapy. Additionally, patients have some degree of pancytopenia with anemia being most prominent. Secondary infection or bleeding is very rare. Some mouth ulcerations and rashes can also be seen. An untoward toxicity relatively unique to this agent is hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceremia, and hyperlipidemia. Pancreatitis may occur secondary to the elevated tryglycerides. While therapy can be cumbersome with its weekly intravenous schedule, its overall toxicity is mild even in the overall more debilitated patients who have been studied. Alternate Doses and Schedules For two of the agents, alternative dosing and scheduling have been attempted. Sunitinib can be given continuously at 37.5mg po daily. This schedule avoids the break in treatment for 2 weeks where conditions may favor regrowth. However, the lower dose, continuous schedule was not superior and the overall response rate appeared lower than the standard 50mg daily for 4 of 6 weeks. This schedule was not directly compared to the standard schedule in a randomized trial. Additionally, toxicity was similar with the continuous dosing schedule. Attempts have been made at dose escalation of Sorafenib. There was some evidence from the randomized phase II trial of Sorafenib that those who progressed on 400mg BID could be dose escalated to 600 mg BID. Amato and his colleague have attempted to follow a very aggressive dose escalation in treatment naïve patients. In 44 patients, 41 were able to be escalated to 600mg BID after 1 month and then 32 of these patients were able to be increased to 800mg BID after 2 months65. There was a very high response rate of 55% with 16% complete responses. Though the median PFS was just 8+ months and overall survival was at 11.5 months. This is surprisingly short considering the high response rate and suggests that these are short clinical responses that may be limited by toxicities. This must be reproduced in a multi-center phase II study, but if positive 35

- 42. it would be quite significant and ways to ameliorate Sorafenib toxicities would take on even more importance. Until then these results should be looked at with great caution and only considered in a trial setting. Therapy in Patients Who Have Failed Front Line Anti-angiogenesis Therapy There is little information to guide therapy in patients failing their initial treatment. One study has provided some direction in patients who have failed Bevacizumab66. These patients with progressive disease while on Bevacizumab were then treated with Sunitinib. Therapy had to be initiated within several months of stopping Bevaciumab treatment. Of 61 patients there was an objective response rate of 23% with a median progression-free survival of 30.4 weeks (7.4 mos) and overall survival of 47.1 weeks (10.9 months). Of the 57 patients with post-treatment tumor evaluations 51 (84%) demonstrated some degree of tumor regression. Patients who had failed to have any prior response to Bevacizumab were among those who demonstrated objective responses to Sunitinib (11/14 patients with PR). To date, this represents the most mature study of second line therapy. Rini, et al. reported on a cohort of 62 patients who had failed Sorafenib and were subsequently treated with another multi-targeted kinase inhibitor, Axitinib with potent activity against all three VEGFR1, 2,and 3.67 Many of these patients had not only failed Sorafenib, but also Sunitinib, cytokines, and chemotherapy. Of 62 patients, 21% experienced a partial clinical response and 34% had stable disease for at least 3 months. Hypertension as was previously observed in frontline studies was the most problematic side effect from Axitinib. Finally, Escudier has reported on 90 patients from France who had previously received Sorafenib and following progression were switched to Sunitinib (68 patients) and 22 patients who had failed Sunitinib and were then switched to Sorafenib therapy. Among those 68 patients who were switched to Sunitinib there was a 15% objective response rate with an additional 51% with stable disease. The median PFS was 25 weeks. For the 22 patients who had failed Sunitinib and switched to Sorafenib, there was a 9% response rate with stable disease in 55% and median PFS of 17 weeks. While this was only a retrospective study it does support the lack of complete cross resistance for these two drugs even with their similar target profile. Combination Targeted Therapy in Advanced RCC A number of studies have been reported combining several of the active targeted agents including Sorafenib or Sunitinib with Bevacizumab and Temsirolimus with either Bevacizumab, Sorafenib or Sunitinib. While most of these studies enrolled small numbers of patients and included several dose levels, there have been some common findings. In general toxicity of the two agents appears to be exacerbated. There has been an increase in known toxicities such as hand-foot syndrome, hypertension, or proteinuria. In some cases, new toxicities have occurred such as a microangiopathy associated with hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, renal insufficiency and mental status changes. That has been recently observed with Sunitinib and Bevacizumab combination. While some combinations appear to allow full doses of both agents (Bevacizumab and Temsirolimus) most of the combinations required dose reduction of either one or both of the agents. Combinations of Sorafenib and Bevacizumab have required significant dose reductions of both agents. Activity in many cases appears to be preserved but still no formal phase II studies 36

- 43. have been undertaken with any of the combinations. A recently opened randomized phase II trial will explore three of the combinations of Sorafenib with Bevaciumab, Sorafenib with Temsirolimus, Bevacizumab with Temsirolimus, and as a control, Bevacizumab alone. Additionally, another phase III trial is being planned to compare Bevacizumab with Temsirolimus or with IFN. In general, there remains many questions about combination therapy, especially in the face of toxicity and requirements for lower doses of the agents when they are combined. So far complete responses have been as rare as with single agents. It may be in the future that sequential therapy will be considered the best approach to treatment as it is frequently done today. Only through well performed trials will we gain this information. Use of Targeted agents in the treatment of Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma (See Table 3) The role of HIF and its hypoxia induced gene expression program in papillary RCC is not understood. In the past most medical urologists, believed these malignancies responded to chemotherapy based regimens. This was never adequately studied to draw any conclusions. Probably the most convincing information about treatment efficacy in papillary RCC comes from the front line Temsirolimus trial as described above. In this trial out of 626 patients about 19% had non-clear cell histology. Of those where histology was better described 75% had papillary RCC as would be expected. In the two arms of Temsirolimus versus IFN there were 73 patients with non-clear cell histology. In a striking result, the progression-free survival was 7.0 versus 1.4 months favoring the Temsirolimus arm and overall survival was more than doubled in those receiving Temsirolimus with OS of 11.6 months versus 4.3 months for IFN–treated patients. This data has a number of problems; the number of patients is small and the actual with papillary RCC is not definite, but assuming the arms are balanced and most are papillary cancers, these results suggest Temsirolimus is an active drug in papillary RCC. Finally, in a retrospective report recently published from 5 centers in the US and France, the clinical outcomes of Sorafenib and Sunitinib in patients with papillary RCC was reported. Forty-one of the 53 patients had papillary RCC and the response rate was only 4.8% (2/41) and both received Sunitinib. The median PFS for papillary RCC treated with Sunitinib was 11.9 months (13 patients) while for the other 28 patients treated with Sorafenib the median PFS was 5.1 months. Few patients had central pathology review. While the data on Sunitinib is limited with only 13 patients, there appears to be some activity (2/13 patients with PR) and PFS was 11.9 months. On the other hand, therapy with Sorafenib had only a median PFS of 5.1 months and no clinical responses in the 28 patients. It is obvious further information is needed to make any definite decisions on therapy with either Sunitinib, Sorafenib or even Temsirolimus. It is critical to perform large enough multicenter studies with only papillary RCC to better gauge effects of any of the above agents. 37

- 44. Table 3: Experience with Targeted Agents in Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma Drug Histology Patient Response Median PFS Median OS Number Rate Sorafenib Papillary 28 0/28 5.1 mos NA Sunitinib Papillary 13 2/13 11.9 mos NA Temsirolimus Non-clear cell# 37 NA 7.0 mos 11.6 mos Vs IFN 75% Papillary 36 NA 1.4 mos 4.3 mos # Patients all had poor prognostic factors based on MSKCC and Multiple Organ Sites (>3/6 risk factors) Summary (See Table 4) Great progress has been made in a few years as shown in Table 4. Frontline data supports the use of either Sunitinib alone or Bevacizumab with IFN in patients with favorable or intermediate prognostic factors. The role of nephrectomy is not known, but almost all patients enrolled onto previous studies did have nephrectomies. Those patients with poor prognostic factors should probably receive Temsirolimus. Data on Sunitinib is simply not very convincing at this point but there very well could be activity comparable to Temsirolimus. Second line cytokine failures would be appropriate candidates for Sorafenib based on its prolongation in median PFS. Finally those who have failed front line targeted therapy have very little guidance about what treatment should be given next. Bevacizumab failures can receive a significant benefit from Sunitinib and patients who fail one of the MTKI, Sorafenib or Sunitinib can respond with objective clinical responses or stable disease from the other agent. However, this is an area which still requires extensive study. Lastly, patients who are young, healthy, have good organ function, an excellent performance status, and access to an experienced IL-2 center may be considered for high dose Interleukin-255 . It is the only treatment which offers a chance for cure and very prolonged disease free periods. While this number is less than 10%, because of its impact on these patients is so great, some may consider it for frontline therapy and targeted agents after failing IL-2. We have impacted on many more patients that any of the cytokines ever did. While few studies show an overall benefit except for Temsirolimus, those of us taking care of patients have experienced living for a number of years with disease control where in the past their survival was measure in months to a year. This impact will become more clear with time. Hopefully over that time we will gain further insight how to use these agents. 38

- 45. Table 4: Potential Standards for Advanced Stage Clear Cell RCC Setting Therapy First-Line Good or intermediate Sunitinib High-dose IL-2 Therapy risk* Bevacizumab? With IFN? Poor risk* Temsirolimus/ Sunitinib Second- Prior cytokine Sorafenib Line Prior VEGFR Temsirolimus?? Therapy inhibitor Prior mTOR inhibitor No data available 39