Unit 11 Prov Japan Asia 1420 Ol Ha

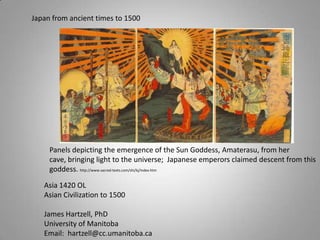

- 1. Japan from ancient times to 1500 Panels depicting the emergence of the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu, from her cave, bringing light to the universe; Japanese emperors claimed descent from this goddess. http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/kj/index.htm Asia 1420 OL Asian Civilization to 1500 James Hartzell, PhD University of Manitoba Email: hartzell@cc.umanitoba.ca

- 2. Major Time Periods in early Japanese History/Civilization Paleolithic 35,000-14,000 bce (21,000 years) Jomon 14,000-400 bce (13,600 years) Yayoi 400 bce – 250 ce (650 years) Kofun 250-538 ce (288 years) Asuka 538-710 ce (172 years) Nara 710-794 ce (84 years) Heian 794-1185 ce (391 years) Kamakura 1185-1333 ce (148 years) Muromachi 1336-1573 (237 years) (Ashikaga) Satellite view of Japan http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geography_of_Japan http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japan

- 3. Jomon and Yayoi covered in earlier unit (number) Ainu people—found today in Hokkaido, northern Island of Japan and and Ryukyu islands in Okinawa , are ethnically different from other Japanese, with Caucasian features, lighter skin and more body hair, larger noses and rounder eyes; traditionally men grew full beards and never shaved. The group is considered the modern remnant of the Jomon. Spoken Ainu differs significantly from Japanese in its syntax, phonology, morphology, and vocabulary; only between 15-100 native speakers of Ainu are alive today. Most of modern Japanese are 80% Yayoi and 20% Jomon. Yayoi improvements came with agriculture, starting with a small number of people, their large food supply soon allowed them to overwhelm the Jomon. In the modern era the Japanese government made efforts to integrate the Ainu into the broader society, resulting in a dilution of their distinct identity. Hokkaido Island (in red) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hokkaid%C5%8D Okinawa Prefecture consists of hundreds of the Ryukyu Islands in the East China Sea, a 1000+ km long chain stretching from Kyushu (Japan’s most southwestern island) southwest to Taiwan. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okinawa Ainu man, circa 1880. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ainu_people

- 4. Kofun/Tomb period: 250-538/552 (no written records from Japan, just archaeological evidence) “Kofun” = particular type of ancient Japanese burial mound, ranging fro several meters to the largest 400m long. Shapes are keyhole, square, round, and two conjoined rectangles. Inside of tombs are tightly assembled rocks, white lime cement plasters with colored pictures illustrating court life or star constellations. Stone or sometimes wooden coffins are placed in the central chamber with burial objects, swords and bronze mirrors. Keyhole-shaped kofun disappeared in late 6th century, probably because of Yamato court reformation and the introduction of Buddhism. Nara plains is the area with most of the tombs, south of Kyoto, south and east of Osaka. The keyhole-shaped kofun tomb of Japan's Emperor Nintoku lies nestled in the bustling seaport of Sakai in an undated aerial photo. The fifth-century tomb is the largest in Japan. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/bigphotos/37310193.html Location of Sakai, just SE of Osaka http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japan_map

- 5. Necklace of jade magatama or curved beads, of the type found in Kofun burials. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magatama The stone chamber of Ishibutaikofun, the tomb of Soga no Umako, Asuka village, Nara Prefecture (white figure, rear of walking person, illustrates scale)7th century http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kofun Takamatsuzuka Tomb mural, Asuka village, Nara Prefecture http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takamatsuzuka_Tomb

- 6. Kofun burial mounds, which entombed leaders, included, in a manner similar to the ancient Chinese burial traditions, clay figures and other artifacts representing items considered needed by the deceased to either protect them or supply them in the afterlife. KofunHaniwa soldier http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kofun_period Kofun period Haniwa chieftain, Ibaraki, circa 500 CE. British Museum http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kofun_period Haniwa horse statuette, complete with saddle and stirrups, 6th century http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haniwa

- 7. Wei Zhi mention of early Japanese The Chinese began keeping systematic histories during the Han dynasty, though there are earlier works. The 297 ce Wei Zhi (“Records of Wei”) includes the history of the Cao Wei kingdom, one of the three kingdoms in China (Wei, Shu and Gu) from 220-280 ce. The Wei Zhi includes a section on "Encounters with Eastern Barbarians” describing the “Wo-ren” or Japanese, derived from the reports of Chinese envoys who had traveled to Japan, and from earlier reports in the 82ce Han Shu (Book of Han), which mentioned the 100 communities of Wo across the ocean that had maintained trade with China. The Wei Zhi stated that the Wa/Wo people lived in the middle of the ocean on the mountainous islands southeast of the Tai-fang prefecture. Wa envoys traveled to the Han court, and during the period of the Wei Zhi writing, 30 Japanese communities maintained communication by envoys. The territories of Cao Wei (in yellow), 262 ce http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cao_Wei The Wei Zhi includes a section describing a Japanese Queen Himiko/Pimiko, and her government’s relations with the Wei: “The country formerly had a man as ruler. For some seventy or eighty years after that there were disturbances and warfare. Thereupon the people agreed upon a woman for their ruler. Her name was Pimiko. She occupied herself with magic and sorcery, bewitching the people. Though mature in age, she remained unmarried. She had a younger brother who assisted her in ruling the country. After she became the ruler, there were few who saw her. She had one thousand women as attendants, but only one man. He served her food and drink and acted as a medium of communication. She resided in a palace surrounded by towers and stockades, with armed guards in a state of constant vigilance.” (tr. Tsunoda 1951:13) Queen Himiko's emissaries visited the court of Wei emperor Cao Rui in 238, and he replied. “Herein we address Pimiko, Queen of Wa, whom we now officially call a friend of Wei. [… Your envoys] have arrived here with your tribute, consisting of four male slaves and six female slaves, together with two pieces of cloth with designs, each twenty feet in length. You live very far away across the sea; yet you have sent an embassy with tribute. Your loyalty and filial piety we appreciate exceedingly. We confer upon you, therefore, the title "Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei," together with the decoration of the gold seal with purple ribbon. The latter, properly encased, is to be sent to you through the Governor. We expect you, O Queen, to rule your people in peace and to endeavor to be devoted and obedient.” (tr. Tsunoda 1951:14) Translations from : TsunodaRyusaku, tr. 1951. Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: Later Han Through Ming Dynasties. Goodrich, Carrington C., ed. South Pasadena: P. D. and Ione Perkins. Adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen_Himiko

- 8. The Asuka Period 538-710 ce. In the mid-6th century, Japan's nation building began in the area of the modern village of Asuka in present-day Nara Prefecture. The capital was moved from Asuka to Fujiwara-kyo, then to Heijo-kyo in 710. The name “Asuka period” was introduced by Japanese art scholars in the early 1900s. In many ways this period laid some of the groundwork for the development of the classic Japanese political identity. Buddhism arrived from Korea, leading to an end of the Kofun tomb burial practices. Though some scholars correlate the end of the Asuka period with the Taika Reform of 646, it’s generally accepted that the transfer of the capital to the Hiejo Palace in Nara marks the end of the Asuka period, and the beginning of the Nara Period. The Asuka period is also sometimes known as the Yamato period or the Yamato court as the Yamato people consolidated political power during this time through clans and extended families headed by patriarchs, with family members becoming the aristocrats and the source of the rulers and emperors. The Yamato developed a central administration, an imperial court, adopted written Chinese, formalized administrative units, and organized society along professional occupations. Agricultural lands were taken over and run by the government. Emperor Kimmei, the 29th emperor according to traditional Japanese histories, and the first who’s rule can be verified with modern historiography, ruled from 539-571, and is generally considered the first of the Asuka rulers. . According to the story told in the Nihon Shoki, one of the two ancient histories of Japan, the Paekche Korean emperor sent a mission to Japan in 552 that included the gift of a Buddha statue, manuscripts, and monks. Controversy between supporters of Buddhism and traditional Japanese beliefs led to a political split between the traditionalist Mononobe clan and the Buddhism-supporting Soga clan, leading to the decisive battle of Shigisn in 587, which the Soga won. In mid-6th century the Yamato Imperial Court invited a priest from Paekche (Korea), to teach them astronomy, geography, and calendar making. Reportedly, Japan organized its first calendar in the 12th year of Suiko (604) (see http://www.ndl.go.jp/koyomi/e/history/02_index1.html for images of this earliest Japanese calendar). Great Buddha of Asuka-dera, made in 609ce by a Korean immigrant’s son, it is the oldest Buddha sculpture in Japan. It is housed in Japan’s oldest Buddhist temple, built in 596. . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asuka-dera

- 9. The Soga chieftain Soga no Umako in 587 installed his nephew as emperor, later assassinating him and replacing him with Empress Suiko (reigned 593-628), who served as a figurehead for Umako and Prince Regent ShotokuTaishi (574-622). Shōtoku was a devout Buddhist, well educated in Chinese, and sympathetic to Confucian ideals. He introduced Confucian models of rank and etiquette, adopted the Chinese calendar, promulgated a 17 article constitution, and introduced a system of five provinces and seven circuits (Gokishichidō) that included roads from the capital to each provincial capital. He built many Buddhist temples, had court chronicles compiled (again, following the Chinese model), and sent students and emissaries to China to study Buddhism and Confucianism, some of whom remained in China for 20 years (Shotoku later wrote commentaries on some of the Buddhist texts brought back from China). He also sought to establish a sense of equality with China, sending an official correspondence to the Chinese emperor: "From the Son of Heaven in the Land of the Rising Sun to the Son of Heaven of the Land of the Setting Sun." Japan sent seven emissaries to Tang China between 600-659, but then none for the next 32 years. The Japanese and Koreans, exchanged 28 ambasasdors, and the Yamato’s even sent armed forces to aid the Baekie kingdom in 660-663 during its unsuccessful rebellion against the Tang and Silla. The Baekie royal family and many Korean refugees all found refuge in Japan at this time. In 645 there was a palace coup in Japan against the dominant Soga clan, introducing the 4 year Taika Reform. What had become the private lands of great clans were taken back into public ownership; land reverted to the state upon the death of the owner, rather than being passed down to the descendants. A tax system on goods was introduced, as well as a labor tax for military service and building public works. Hereditary chieftain titles were abolished, and a ministerial system was introduced. The new rulers took the name Fujiwara, and the notion of the divine origin of the Emperor came into use. TōhonMiei, Portraits of Prince Shōtoku and his two sons, 8th century? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asuka_Period The Taika reform included the introduction of the Ritsuryō system, which was gradually further codified into the Taiho Code by 701. This system, based on the Chinese methods, provided for systematic administration and legal sanctions. In two significant ways The Taihō Code differed from the Chinese Confucian model: it allowed government positions and social class to be based on birth, rather than on merit, and defined the Emperor’s power as based on imperial lineage, not righteousness under the mandate of heaven.

- 10. Heijō-kyō, was the capital city of Japan for all but 5 years between 710 and 794 in the “Nara period.” The Japanese government and partners have been reconstructing the buildings from the ancient palace as part of a build up to the celebration of the 1300th anniversary in 2010. So far the Suzaku front gate and the palace’s East Garden have already been reconstructed, and the main audience hall will be ready for the 2010 celebrations. The Palace site is part of the UNESCO World Heritage sites in Nara. The plan of the capital city was modeled on the Tang Chinese capital of Chang-an, then the largest city in the world. Groundplan of HeijōKyō http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heijo-kyo Reconstructed Suzakumon of Heijō Palace in Nara http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heijo-kyo

- 11. The Nara period saw major consolidation of Japanese political, literary, artistic and religious developments. The earliest Japanese histories, the Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720) were written during this time. Emperor Shomu (724-749) and his Fujiwara consort Empress Kōmyō made Buddhism the "guardian of the state" and a way of strengthening Japanese institutions. Shomu had built the Todai-ji (‘Great Eastern Temple) with its 15m high 500 tonne gilt bronze Buddha who was identified with Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, marking the start of a gradual syncretism of Buddhism and Shinto. Shōmu proclaimed himself "Servant of the Three Treasures”, Buddha, Dharma (the law or teachings of Buddhism), and Sangha (the Buddhist community). Upon retirement Shomu became a Buddhist priest, and Komyo a nun. Chinese schools of Buddhism were introduced by monks arriving from the mainland. Literate and educated, Japanese monks also worked as court scribes and administrators, on public works, and on geographer projects mapping the Japanese islands. Ordination of monks was controlled through the Buddhist administrative headquarters at the Toda-ji temple, which was itself controlled by the government. The Taiho Code was revised during the Nara period with major work on the renamed Yoro Code completed in 718, incorporating further Japanese specific modifications to the Confucian model. Nara era land policies were changed in 743 to promote land reclamation (from wastelands etc into arable land for farming), allowing semi-permanent succession of these lands within families. Wealthy families vigorously pursued such reclamation, undermining public land ownership and literally laying the groundwork for the development of the “shoen” or estate system. Japanese diplomatic ship used to carry envoys to Tang China From the Weekly Asahi Encyclopedia Supplement "Japanese Diplomatic Ship to Tang China: Reinterpreting History" (illustrated by KenzoTanii; edited by Kenji Ishii) http://www.1300.jp/foreign/english/kyuuseki/long_term/index.html

- 12. During the Nara period, c. 759 ce, the Man'yōshū ("Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves") was compiled -- the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, including poems written between 347ce – 759 ce, many by women or by the emperors and empresses, with most poems in the collection post-dating 600ce. Following are a few excerpts in translation: 1) In 673, the Emperor Temmu moved the capital back to Yamato province on the Kiyomihara plain, naming his new capital Asuka. The Man'yōshū includes a poem written after the Jinshin conflict of 672 had ended: Our Sovereign, a god, Has made his Imperial City, Out of the stretch of swamps, Where chestnut horses sank To their bellies. -- Ōtomo Miyuki. (Nippon GakujutsuShinkokai. (1969). The Man'yōshū,p. 60.) 2) Emperor Jomei (593-641 r 629-641)wrote the following when he climbed Kagu hill to view his lands (he was the father of both Emperors Tenji and Temmu): Of many hills in the land of Yamato, I climb heavenly Kagu Hill richly adorned with green foliage,and stand on the summit to view my realm, I see smoke rising on the open plain of land and gulls taking off from the surface of the lake. A splendid land, is this land of Yamato! 3) Empress Iwanohime (First half of the 5th century), the 4th of four poems expressing her longing for Emperor Nintoku: The consort empress of Emperor Nintoku, the sixteenth sovereign who established his capital at Niniwa (now Osaka). Empress Iwanohime was famous for her jealousy of the Emperor's second wife and his other amorous interests: Whither will the fog of passion for him vanish, as does the morning mist hanging over the rice ears in the autumn field? 4) Sami Manzei (active 704-731) was the Buddhist name taken by Kasa no Maro, a high-ranking government official when he became a sami (or shami), a Buddhist acolyte. In 723 he was sent to the Province of Tukushi to supervise the construction of Kanzeonji, a large Buddhist temple near Dazaifu in Kyūshū. In 728 he met the famed poet OtomoTabito and became part of his poetic circle: To what shall I compare this life? It is like a boat that rowed away at dawn leaving no wake behind it. Source: http://home.earthlink.net/~khaitani1/mysx1.htm#1-2 Man'yoshu Best 100 with Explanations and Translationcompiled by Kanji Haitani Portions or all of the text on this website may be reproduced electronically or in print for educational, non-profit purposes, provided credit is given by reference to the URL of the front page of this website or by including the following copyright notice: Copyright 2005-2007 Kanji Haitani

- 13. ŌtomoTabito (665-731) was Governor-General of Dazaifu 727/8 - 730, and center of the great literary circle. In 728, soon after he arrived at his new post at Dazaifu, his beloved wife died there. In many of his poems he cherished the memories of his late wife. Oh, how ugly! Take a good look at a man who puts on airs and would not drink sake, and he looks just like a monkey. Yamanoue Okura (660-ca 733) was selected as a member of the government mission sent to the court of T'ang China. His studies there (702 to 704 or 707) enhanced his reputation as a scholar of Chinese. In 721, he was appointed tutor to the Crown Prince (later Emperor Shōmu). In 726, at age 67, he was appointed Governor of the Province of Chikuzen in northern Kyūshū where he became part of OtomoTabito’s literary circle. Okura is known for his unique style of realistic and meditative poetry that expressed moral and social concerns left unarticulated by the other Man'yō poets. When I eat melons, I think of my children. When I eat chestnuts, I miss them even more. By what turn of fate did they come to me? Flickering before my eyes incessantly, they would not let me sleep in peace. http://home.earthlink.net/~khaitani1/mysx1.htm#1-2 Man'yoshu Best 100 with Explanations and Translationcompiled by Kanji Haitani Portions or all of the text on this website may be reproduced electronically or in print for educational, non-profit purposes, provided credit is given by reference to the URL of the front page of this website or by including the following copyright notice: Copyright 2005-2007 Kanji Haitani A poem by Empress Gemmei (Gemmei-tenno, r. 707-721; it was she who moved the Japanese capital to Nara in 710) in 708, including a reply by one of the ladies of her court: Listen to the sounds of the warriors' elbow-guards; Our captain must be ranging the shields to drill the troops.– Gemmei-tennō Reply: Be not concerned, O my Sovereign; Am I not here, I, whom the ancestral gods endowed with life, Next of kin to yourself? -- Minabé-hime Source: Nippon GakujutsuShinkokai. (1969). The Manyōshu,p. 81, cited from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empress_Gemmei

- 14. The Heian Period From 794-1185 the capital of Japan was in Heian-kyo (modern Kyoto). This era marked the height of Chinese influence on Japan through Buddhism, Taoism, artistic, literary and political influence, and we have many surviving examples of artistic brilliance from these centuries. The government was in control of the Fujiwara clan, the clan that had succeeded the Soga clan in the Taika reform during the Nara period. In 784 Emperor Kammu moved the capital from Nara to Nagaoka, and then in 794 to Heian-kyo,iin part to weaken the influence of the Nara Buddhist establishments and strengthen the hand of the government. Heian-kyo remained the location of Japan’s imperial capital for the next 1000 years. The emperor had 16 wives (empresses and consorts) who bore him 32 children, of whom 3 later became emperors. Kammu funded an expedition for two Japanese monks, Saicho (767-822) and Kukai (774-835) to travel and study in China. Saicho spent 11 months in Japan from 804-805 (in his late 30’s), while Kukai (in his early 30’s) spent about two years in China. The government expedition included four ships, with Kūkai on the first ship, and Saidho on the second. The third ship turned back during a storm, and the fourth was lost at sea. Kūkai's ship was initially impounded in Fujian port, but Kukai wrote a letter in fluent Chinese to the provincial governor and this secured their release (note the power of a formal education!). Saicho, whose home temple was on Mount Hiei, returned to introduce the Tian-tai (or Tendai) school of Buddhism, which required a twelve-year course of study and meditation. He gained official patronage from the court, with many of his monk graduates working directly for the government. Kukai brought Vajrayana Buddhism back to Japan, forming the Shingon school of Esoteric Buddhism. Ten years after his return he became head of the Toda-ji temple. Both Saicho’sTendai and Kukai’sShingon remain strong influences in Japanese Buddhism even today. For the interested student: Both Saicho and Kukai’s full biographies are rich in historical and cultural details about 8-9th century Japan and China. Both stories also provide many insights into the development of the Japanese Buddhist traditions.

- 15. The Heian era saw the compilation or creation of some of most famous works of Japanese and world literature. The KokinWakashū(or Kokinshū,; "Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times") is a poetry anthology finished by four court poets under imperial order by about 920 ce. The chapters are: 1-2 Spring 3 Summer 4-5 Autumn 6 Winter 7 Congratulations 8 Partings 9 Travel 10 Acrostics Love 11-15 Love Miscellany 16 Laments 17-18 Miscellaneous 19 Miscellaneous Forms 20 Traditional Poems from the Bureau of Song. MurasakiShikibu 973-1014 or 1025, author of Lady Murasaki)’sTale of Genji: The Genji was written in court Japanese, a highly inflected language with complex grammar, and delivered to the court’s female aristocracy chapter by chapter in installments. It is considered one of the world’s first ‘novels,’ with a central character and hundreds of major and minor characters. The chapters follow the main character’s life, with his many loves and adventures, with all the other characters also aging naturally along with him, and all retaining their appropriate family and feudal relationships. No one has a name, as Heian court public deferential manners determined characters could only be referred to by their honorifics (“his Excellency”), their professional title, or their relation to other characters. Modern translations use nicknames to keep track of who is who. A handscroll painting dated circa 1130, illustrating a scene from the "Bamboo River" chapter of the Tale of Genji. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Genji_emaki_TAKEKAWA.jpg

- 16. In keeping with the naming conventions of Japanese poetry, the Genji chapter names followed certain well-established themes. Remember the story was delivered to the court aristocracy sequentially, somewhat akin to a modern dramatic series on television, so each chapter title held an allure appropriate to the time of year and the progress of the overall story: 1 “Paulownia Court” “Paulownia Pavilion” 2 “Broom Tree” 3 “Shell of the Locust” “Cicada Shell” 4 “Evening Faces” “Twilight Beauty” 5 “Lavender” “Young Murasaki” 6“Safflower” 7 “Autumn Excursion” “Beneath the Autumn Leaves” 8 “Festival of the Cherry Blossoms” “Under the Cherry Blossoms” 9 “Heartvine” “Heart-to-Heart” 10 “Sacred Tree” “Green Branch” 11“Orange Blossoms” “Falling Flowers” 12 “Suma” 13 “Akashi” 14 “Channel Buoys” “Pilgrimage to Sumiyoshi” 15 “Wormwood Patch” “Waste of Weeds” 16 “Gatehouse” “At The Pass” 17 “Picture Contest” 18“Wind in the Pines” 19 “Rack of Clouds” “Wisps of Cloud” 20 “Morning Glory” “Bluebell” 21 “Maiden” “Maidens” 22 “Jeweled Chaplet” “Tendril Wreath” 23 “First Warbler” “Warbler‘s First Song” 24 “Butterflies” 25 “Fireflies” 26 “Wild Carnation” “Pink” 27 “Flares” “Cressets” 28 “Typhoon” 29 “Royal Outing” “Imperial Progress” 30 “Purple Trousers” “Thoroughwort Flowers” 31 “Cypress Pillar” “Handsome Pillar” 32 “Branch of Plum” “Plum Tree Branch” 33 “Wisteria Leaves” “New Wisteria Leaves” 34 “New Herbs, Part I” “Spring Shoots I” 35 “New Herbs, Part II” “Spring Shoots II” 36 “Oak Tree” 37 “Flute” 38 Suzumushi “Bell Cricket” 39 “Evening Mist” 40 “Rites” “Law” 41 “Wizard” “Seer” Vanished into the Clouds“ 42 ”His Perfumed Highness“ ”Perfumed Prince“ 43 ”Rose Plum“ ”Red Plum Blossoms“ 44 ”Bamboo River“ 45 ”Lady at the Bridge“ ”Maiden of the Bridge“ 46 ”Beneath the Oak“ 47 ”Trefoil Knots“ 48 ”Early Ferns“ ”Bracken Shoots“ 49 ”Ivy“ 50 ”Eastern Cottage“ 51 ”Boat upon the Waters“ ”A Drifting Boat“ 52 ”Drake Fly“ ”Mayfly“ 53 ”Writing Practice“ 54 "Floating Bridge of Dreams”. Lady Murasaki continued to produce chapters throughout her own entire adult life, ceasing only with her own death. The current form of the story is accepted as having existed in 1021. There is still debate whether some of the final chapters are hers or those of her daughter. The text has been translated into several modern languages – it is a richly rewarding story for those interested in the Japanese court life in the early 11th century. The GenjiMonogatariEmaki, a pictorial hand scroll of the text, dates from 1120-1130, and is the oldest surviving non-Buddhist scroll in Japan. Originally about 450 feet long, it was composed of 20 rolls, over 100 paintings, and over 300 sheets of calligraphy. Only about 15% of this survives. Note the construction of the parasaol, essentially the same as umbrellas in use today http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Genji_emaki_Yomogiu.JPG

- 17. The Tale of Gengi was written in “Monogatari”, an extended prose narrative tale comparable to the epic, closely tied to oral story telling traditions. Many of the great works of Japanese fiction use this form, which was prominent from the 9th-15th centuries ce. Of the 198 in existence in 1271, about 40 still exist. The term “monogatari” is still used in Japanese titles of foreign literature such as Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. A scene of Azumaya from the scroll owned by Tokugawa Art Museum http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genji_Monogatari_Emaki The GenjiMonogatariEmaki is characterized by two pictorial techniques, funkinukiyataiand hikimekagibana. Fukinukiyatai means “blown away roof”, a style of architectural painting providing a bird’s eye view of the building’s interior, sometimes with removal of the partitions and screens between rooms. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Genji_emaki_YADORIGI_2.JPG

- 18. The Tale of Genji’s author also kept a highly literate diary; an excerpt follows, which gives a sense of court life at the time: THE DIARY OF MURASAKI SHIKIBU (Quoted directly from: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/omori/court/murasaki.html) 1007-1010 ce ("The Diary of MurasakiShikibu." by MurasakiShikibu (978- )Publication: Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan. translated by Annie Shepley Omori and Kochi Doi, with an introduction by Amy Lowell. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920, pp. 69-145. ) “As the autumn season approaches the Tsuchimikado becomes inexpressibly smile-giving. The tree-tops near the pond, the bushes near the stream, are dyed in varying tints whose colours grow deeper in the mellow light of evening. The murmuring sound of waters mingles all the night through with the never-ceasing recitation of sutras which appeal more to one's heart as the breezes grow cooler. The ladies waiting upon her honoured presence are talking idly. The Queen hears them; she must find them annoying, but she conceals it calmly. Her beauty needs no words of mine to praise it, but I cannot help feeling that to be near so beautiful a queen will be the only relief from my sorrow. So in spite of my better desires [for a religious life] I am here. Nothing else dispels my grief –it is wonderful! It is still the dead of night, the moon is dim and darkness lies under the trees. We hear an officer call, [Page 72] "The outer doors of the Queen's apartment must be opened. The maids-of-honour are not yet come–let the Queen's secretaries come forward! " While this order is being given the three-o'clock bell resounds, startling the air. Immediately the prayers at the five altars begin. The voices of the priests in loud recitation, vying with each other far and near, are solemn indeed. The Abbot of the Kanon-in Temple, accompanied by twenty priests, comes from the eastern side building to pray. Even their footsteps along the gallery which sound to'-do-ro to'-do-ro are sacred. The head priest of the Hoju Temple goes to the mansion near the race-track, the prior of the Henji Temple goes to the library. I follow with my eyes when the holy figures in pure white robes cross the stately Chinese bridge and walk along the broad path. Even AzaliahSaisa bends the body in reverence before the deity Daiitoku. The maids-of-honour arrive at dawn. I can see the garden from my room beside the entrance to the gallery. The air is misty, the dew is still on the leaves. The Lord Prime Minister is walking there; he orders his men to cleanse the brook. He breaks off a stalk of omenaishi [flower maiden] which is in full bloom by the south end of the bridge. He peeps in over my screen! His noble appearance embarrasses us, and I am ashamed of my morning [not yet painted and powdered] face. He says, "Your poem on this! If you delay so much the fun is gone!" [Page 73] and I seize the chance to run away to the writing-box, hiding my face– Flower-maiden in bloom– Even more beautiful for the bright dew, Which is partial, and never favors me. "So prompt!" said he, smiling, and ordered a writing-box to be brought [for himself]. His answer: The silver dew is never partial. From her heart The flower-maiden's beauty.”

- 19. Among other female literary figures, perhaps the most famous poet was Izumi Shikibu(970-1030), who Influenced nearly all subsequent Japanese poets. She was a contemporary of MursakiShikibu, wrote many love poems, and was later named a member of the 36 Medieval Poetry Immortals: Trampling the dry grass the wild boar makes his bed, and sleeps. I would not sleep so soundly even were I without these feelings.(GoshuiWakashu14:821) My black hair is unkempt; unconcerned, he lies down and first gently smooths it, my darling!(GoshuiWakashu13:755) They say the dead return tonight, but you are not here. Is my dwelling truly a house without spirit?(GoshuiWakashu10:575) (Adapted from Wikipedia entry on Izumi Shikibu). See http://chnm.gmu.edu/wwh/p/215.html and http://chnm.gmu.edu/wwh/p/216.html for excerpts from The Pillowbook (986-1000 ce) by SeiShônagon, a lady-in-waiting to Empress Teishi (or Sadako), and another of the most famous literary works of the era (note they are by women) including the following passage (Source: Morris, Ivan, trans., The Pillowbook of SeiShônagon. London: Penguin Books, 1971): “High office is, after all, a most splendid thing. A man who holds the Fifth Rank or who serves as Gentleman-in-Waiting is liable to be despised; but when this same man becomes a Major Counsellor, Great Minister, or the like, one is overawed by him and feels that nothing in the world could be as impressive. Of course even a provincial governor has a position that should impress one; for after serving in several provinces, he may be appointed Senior Assistant Governor-General and promoted to the Fourth Rank, and when this happens the High Court Nobles themselves appear to regard him with respect. After all, women really have the worse time of it. There are, to be sure, cases where the nurse of an Emperor is appointed Assistant Attendant or given the Third Rank and thus acquires great dignity. Yet it does her little good since she is already an old woman. Besides, how many women ever attain such honours? Those who are reasonably well born consider themselves lucky if they can marry a governor and go down to the provinces. Of course it does sometimes happen that the daughter of a commoner becomes the principal consort of a High Court Noble and that the daughter of a High Court Noble becomes an Empress. Yet even this is not as splendid as when a man rises by means of promotions. How pleased such a man looks with himself!”

- 20. The Kamakura Period 1185-1333 Throughout the Heian period the Fujiwara controlled the throne for about 200 years, up until the reign of Emperor Go-Sanjo (1068-1073), who sought to restrict Fujiwara political and economic power, and reassert central government control over the shoenestates. He introduced the Incho Office of the Cloistered Emperor, which formalized the role of retired emperors, who typically became Buddhist monks, continuing to playing a role in government. The role of a retired emperor, one who abdicated (DaijōTennō), had been formalized already in the Taiho Code, with the first example being Empress Jito in the 7th century. The term Daijō Hōō referred to a Cloistered Emperor, one who retired/abdicated, and then entered a Buddhist monastic community. Emperor Shirakawa, in 1086, became DaijoHoo in favor of his 4 year old son, thus effectively preventing his own younger brother from seizing the throne. Shirakawa’sinsei System of behind the scenes government lasted until 1129 (45 years), complete with a government department under his direct control, and his own army. This had a major impact on Japanese government political power, and his example was followed by a series of emperors through most of the Kamakura period. The Tale of Hōgen, The Tale of Heijeand the Tale of Heike are threemonogatariclassic Japanese histories that tell the stories of the great battles that led to the founding of the Kamakura Shogunate. The Hogen Rebellion was a civil war in 1156 that established the dominance of the samurai clans, led by two samurai allies, Taira no Tadamori and Minamoto no Yoshitomo. The Tale of Heije tells of the Heiji Rebellion 1159-1160, when these former allies turned against each other. At the end of the battle, Taira no Tadamori was victorious, executed his former ally and his two eldest sons, and exiled the three remaining sons, Yoritomo, Noriyori and Yoshitsune. The Tale of Heike is the epic tale of the Genpei War (1180-85), when the Minamoto clan and their former allies, led by the exiled Minamoto sons, rose up against the Taira, eventually defeating them. Below are some details from a panel in the Tale of Heike depicting a battle scene from the Genpei War (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genpei_War)

- 21. Minamoto no Yoritomo was founder and first shogun of the Kamakura Shogunate. He obtained the title from the Emperor of seii tai-shōgun and ruled from Kamakura 1192-1199. Kamakura, on the east coast of Japan, about 30km south of modern Tokyo, is a natural fortress, surrounded north, east and west by mountains, protected by open water to the south. Until modern times land entrances were only through narrow passes called "Kamakura's Seven Mouths". Minamoto no Yoritomo chose it as his base partly for this natural defensability. After Yoritomo’s death, beginning in 1203 onwards, his wife’s family, the Hojo clan, took control of the government through the office of the Shikken or regent. The Kamakura shogunate allowed two contending imperial lines—known as the Southern Court, or junior line, and the Northern Court, or senior line—to alternate on the throne. Between 1266 and 1272, Kublai Khan, the Mongolian ruler of China and Korea, sent emissaries to Japan demanding they surrender and become a vassal state. The Japanese refused, first sending the emissaries back empty-handed, then refusing to allow them to land. In 1274 the Khan’s fleet of 300 large ships, and about 400 smaller craft, carrying about 23,000 Mongol, Chinese and Korean troops attacked. They overwhelmed the Tsushima and Ikli islands in the Korean strait, killing many, then landed at Hakata Bay, northwest Kyushu Island. After initial success, a substantial portion of the fleet was sunk in a typhoon, and the samurai managed to board the remaining ships and defeat the force in hand-to-hand combat – a specialty of the samurai fighting culture. IN 1275 and then in 1279, the Khan again sent emissaries who refused to leave without an answer. The Japanese sent them overland to Kamakura, where they were beheaded both times. A much larger invasion force was sent in 1281, with one group of 900 ships and 40,000 troops sailing from Korea, and another of 3500 ships and 100,000 troops sailing from China. The Japanese had heavily fortified the coast, and repelled the initial attacks. For a second time an enormous typhoon occurred, this time lasting two days and nights and destroying most of the Mongol fleet. The saving typhoons became known as Kamikaze, “Divine winds.” Portrait of Yoritomo, copy of the 1179 original hanging scroll, attributed to Fujiwara Takanobu. Color on silk. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yoritomo Kamakura Kyushu Modified from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamakura,_Kanagawa

- 22. In 1318 Emperor Go Daigo took the throne in the South, and began his plans to unseat the Kamakura Shogunate and return Japan to Imperial rule. His first plans were found out by the Shogunate’sRokuharaTandaor secret police in 1324 in the Shochu Incident, but only one of his close advisers was executed. In 1331 Go Daigo attempted to overthrow the Shogunate with an attack in Kamakura, but he was defeated and exiled to the island of Oki off the west coast of Japan. In 1333 he managed to escape, and raised another army against the Shogunate. Meanwhile Ashikaga Takauji, the chief general of the ruling Hojo clan of the Kamakura Shogunate, turned against the Hojo, and fought for the emperor (in the hopes of becoming the new Shogun). In 1333, Kamakura was invaded by Nitta Yoshisada, head of the Nitta family and supporter of the southern court of Emperor Go-Daigo. After failing at two of the mountain passes, Nitta, who had previously lived in the Kamakura area for many years, brought his troops into the city across a narrow strip of sand that appears at low tide. Facing defeat, the regent HojoTakatoki and 870 members of his family barricaded themselves in the family temple complex at Tosho-ji, and all committed suicide, ending Hojo rule in Japan. Imperial rule was restored from Kyoto, with Go-Daigo as emperor, in the so-called Kemmu Restoration. But after just three years (1333-1336) Ashikaga Takauji rebelled, defeated the Emperor’s forces under Nitta Yoshisada at the Battle of Takenoshita, and seized power in Kyoto as the new Shogun, beginning the the Ashikaga Shogunate (1336-1565) or what is also known as the Muromachi Period (see below, after the Buddhism section). Go-Daigo fled and set up the Southern Court in the mountains of Yoshino, beginning the Nanboku-chō Wars—the 60 years’ wars between the northern and southern courts. Ashikaga Takauji ruled from 1338-1358 when he passed away. Before we continue the political history of Japan, we will take a look at some of the major Buddhist developments after Kukai and Saicho.

- 23. During the Kamakura period several Buddhist sects were established by Tendai monks who had trained at the Mt. Heian temple and monastery founded by Saicho: the most famous were Honen, Shinran, Nichiren, Dogen and Eisai. These were distinctly Japanese Buddhist sects, characterized by the now world-famous simplicity and directness. (a) The JodoShinshu The JodoShinshu was founded by Shinran, student of Honen. Shinran refined Honen’s teaching of the “Pure Land Sect” (JodoShu) that recitation of the name of Amitabha (or Amida) Buddha (continuous chanting of the nembutsu, namuamidabutsu), would ensure rebirth in the “Pure Land” Western Paradise. Shinran’s teaching was named JodoShinshu (“The Essence of the Pure Land Sect”) and he taught that faith in Amida could lead to realization of the Pure Land in this life, and rebirth in the Western Paradise. During a period of exile, when Honen and Shinran and nembutsu practice were banned by the Buddhist establishment, Shinran revised teaching developed, and, no longer considering himself a monk, he also married. After the nembutsu ban was lifted and Shinran’s new sect gained official recognition, the tradition of married clergy in JodoShinshu continued – today this is the largest Buddhist sect in Japan. (b) The Nichiren Sect Japanese Buddhist monk Nichiren (1222-1282) founded what came to be called the Nichiren sect. Central to all Nichiren practice is chanting of the mantra Nam(u) MyōhōRengeKyō, which translates as Devotion (or Homage) to the Law (or Dharma) of the Lotus Flower Scripture (or Lotus Sutra), and its chanting isconsidered by Nichiren practitioners as essential to achieving enlightenment. A reasonably good article on the history and content of the Lotus Sutra can be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lotus_Sutra. Nichiren began his teaching in Kamakura city, then the seat of the government, and many of his lay followers were samurai. His career was controversial, in particular due to his sharp criticisms of other Buddhist schools, and he was banned for three years (1271-1274) to the island of Sado, a remote island off the east coast of Japan from which none were expected to return (though he did return). Nichiren’s teaching that all people have an innate Buddha nature and can achieve enlightenment in this current lifetime have proved enormously influential, and over two dozen lineages of his tradition survive today. (c) SotoZen DōgenZenji (1200-1253) left Mt. Heian monastery, and studied with Eisai’s (see (d) following) successor Myōzen; the two traveled to China in 1223 to study with Chan Buddhist masters. “To study the Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things of the universe. To be enlightened by all things of the universe is to cast off the body and mind of the self as well as those of others. Even the traces of enlightenment are wiped out, and life with traceless enlightenment goes on forever and ever.” (source: Kim, Hee-jin. EiheiDogen, Mystical Realist. Wisdom Publications, 2004. ISBN 0-86171-376-1, p. 125). Dogen returned to Japan in 1227/28, promulgating the practice of zazen—simply sitting meditation, and eventually established the Zen Buddhist temple complex Eihei-jiIn the Fukui Prefecture, which remains the main Soto Zen training temple in Japan today. A statue of Nichiren outside Honnoji in the Teramachi District of Kyoto. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nichiren

- 24. Dogen’s death poem, written just before his death in 1253: “Fifty-four years lighting up the sky. A quivering leap smashes a billion worlds. Hah! Entire body looks for nothing. Living, I plunge into Yellow Springs.” (Source: Tanahashi, Kazuaki (tr.) & Loori, Daido (comm.) : The True Dharma Eye. Shambhala, Boston, 2005, p. 219).

- 25. d) Rinzai (Zen) Sect Eisai, 1141-1215, the post-Heian period (1185 onwards), introduced Rinzai sect to Japan A Zen master, he also popularized tea drinking. Eisai From: A Dictionary of Buddhism | Date: 2004 | Author: DAMIEN KEOWN © A Dictionary of Buddhism 2004, originally published by Oxford University Press 2004. Eisai (1141–1215). The founder of the Rinzai school of Japanese Zen. “Born into a temple family, Eisai originally entered the Tendai sect and lived at the Miidera. However, the violent factionalism of the Tendai school at that time repulsed him, and he travelled from place to place seeking teaching. In 1168 he went to China to visit the famous sites of the T'ien-t'ai school (Tendai's Chinese root). He arrived at a time when Ch'an was dominant, and was very excited by its vibrance and novelty. He had no time for formal training, however, since he returned to Japan after only six months. After his return, he continued to serve the Tendai school. Eighteen years later, he returned to China once again, this time staying for four years and studying Ch'an intensively with masters of the Lin-chi school in various temples. He had an enlightenment experience, and returned to Japan in 1191 with the robes and certifications of a Ch'an master. After this, he worked to establish places that would be devoted solely to the study and practice of Ch'an. It is not clear that he wished to found a new school; in fact, he criticized his contemporary Dainichib! N!nin for wanting to do just that. He remained a Tendai monk for the rest of his life and worked at many other projects as well, but it is clear that he at least wanted Zen practice to have a place of its own within the overall framework of Japanese Buddhism. Eisai http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eisai Despite the difficulties imposed by the jealousy of the Tendai establishment, Eisai gained increasing patronage among the aristocracy and rising military class, who were attracted by the vigour and action orientation of his southern Sung-style Zen, as well has by his presentation of Zen as a practice that would help to protect the nation. In 1202 he was granted abbotship of the Kennin-ji, a temple in a government controlled district of Kyoto. There he continued to teach Zen even while the court kept him busy overseeing building and restoration projects and performing Tendai-style esoteric rituals. He died in 1215, without having enjoyed any discernible success in establishing a self-standing Zen institution, and it fell to his spiritual descendants to set up Rinzai as an independent school. Nevertheless, he is honoured as the first transmitter of Rinzai Zen to Japan and the de jure founder of the school.” © A Dictionary of Buddhism 2004, originally published by Oxford University Press 2004 Although Japanese chronicles report that the Buddhist monk Eichu first brought tea from China to Japan in the 9th century, it is Eisai who is credited with really introducing tea drinking to Japan. Returning from China with tea, seeds, and implements, he introduced the “tencha” style of placing the ground tea in a bowl, introducing the hot water, and whipping the mixture – the style at the center of the modern versions of the Japanese tea ceremony, in which tea preparation and drinking is treated as part of a meditation. The seeds he brought back were used to develop the agricultural production of Japanese tea.

- 26. Muromachi Period 1333/6-1565/73/1600: New dynasty of Ashikaga Shoguns Shoguns move the government back to the Muromachi neighborhood of Kyoto, so this period is known (somewhat confusingly) as either the Muromachi period or the Ashikaga period. A major set of developments in the arts, inspired by the Zen Buddhist aesthetic, linking with centuries old Japanese traditions, and sponsored by the Ashikaga Shoguns. By the 1470s civil wars begin that then last for 100 years, leading to the eventual decline of the Shoguns. The Imperial seats during the Nanboku-chō period were in relatively close proximity, but geographically distinct. They were conventionally identified as:Northern capital and imperial court (established by Ashikaga Takauji) : Kyoto Southern capital and imperial court (founded by Go-Daino) : Yoshino. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanboku-ch%C5%8D_period http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:MuromachiSamurai1538.jpg

- 27. (First paragraph is a repeat from above): Imperial rule was restored from Kyoto, with Go-Daigo as emperor, in the so-called Kemmu Restoration. But after just three years (1333-1336) Ashikaga Takauji rebelled, defeated the Emperor’s forces under Nitta Yoshisada at the Battle of Takenoshita, and seized power in Kyoto as the new Shogun, beginning the the Ashikaga Shogunate (1336-1565) or what is also known as the Muromachi Period (see below, after the Buddhism section). Go-Daigo fled and set up the Southern Court in the mountains of Yoshino, beginning the Nanboku-chō Wars—the 60 years’ wars between the northern and southern courts. Ashikaga Takauji ruled from 1338-1358 when he passed away. There was considerable conflict during Ashikaga Takauji’s (r. 1338-1358) lifetime, in part driven not just by the competition from the Southern Court, but also within the Northern Court by competition with his own brother. Much internal conflict under the Ashikaga shogunate was also driven by competing interests over who controlled the public and private lands and their wealth. With Takauji’s death in 1358, his son Ashikaga Yoshiakira became shogun (r. 1358-1367). In 1367 he fell ill, and handed over power to his 11-year old son, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who became the 3rd Ashikaga Shogun from 1368-1394, when he ceded power to his own son, Ashikaga Yoshimochi, who ruled from 1394-1423. Yoshimitsu continued to maintain authority over the shogunate (during his ‘retirement’) until his death in 1408, and is famed for having finally resolved the conflict between the northern and southern courts in 1392. During these years, the Shogunate succeeded in integrating the forces of the semi-independent shugo-s (ostensibly public officials who had considerable independent power over public lands), putting down numerous challenges to their power. Gradually the better organized and increasingly effective Muromachi government overcame resistance from the Southern Court, integrated all their own forces and bureaucracy, and brought the Nanboku-cho conflict to an end in 1392. Ashikaga Yoshimochi broke off trade and diplomatic relations with China in 1411; these were only restored in 1423 by 6th Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshinori (r. 1429-1441). Yoshinori was assassinated at the age of 48, and though his 8 year old son was appointed the next Shogun, this marked the beginning of the breakdown of the Shogunate authority.

- 28. The Ōnin (Civil) War began in 1467 because of a conflict over succession for the next Shogun, and powerful, competing interests of “daimyo” or lords controlling vast areas of land. For 10 years most of Japan became consumed in battle. The complete destruction of Kyoto, the breakdown of Shogun authority (Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who ruled from 1449-1463 did not get involved, and occupied himself with poetry and designing his silver retirement pavilion Ginkaku-ji, modeled on his grandfather Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’sKinkaku-ji), and the rise of power of the daimyo fundamentally altered the political landscape, as various daimyo clans fought for control and supported puppet shoguns. Meanwhile non-central Feudal lords, particularly based in and around Kyushu supported a successful piracy into Korea and along the Chinese coast. These “Wokou”, largely former smugglers and fishermen, began in the 13th century, and they were never completely controlled until the Portuguese arrived in the 1500s. Pictures: Kyoto’s Golden Pavilion (Kinkakuji) – originally the retirement home of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu who maintained actual power from here from 1394 till his death in 1408. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d2/Kinkakuji_winter.jpg http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/54/Kinkaku-ji_reflection_in_pond.jpg

- 29. Beginning with Ashikaga Takauji, the Ashikaga shoguns exercised deep interest and involvement in the arts, sponsoring what became the essential flowering of classical Japanese culture as we know it today. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu in particular promoted trade with Ming China and acquired many works of art in the process. In fact, the majority of the great paintings, ceramics, and calligraphic works brought to Japan from China were carried back by Zen monks who had gone to China to study. Stored in the treasuries of the great Zen monasteries, most of these works were requisitioned by the Ashikaga shoguns and became the property of the shogunate. (Note: for detailed information on many of the following subjects, including Japanese terms in Japanese script, students may wish to consult the Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (JANUS) at http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/). Kitayamabunka(literally “North Mountain Culture”) refers to the location of the Golden Pavilion retirement villa on the north side of Kyoto, and the period of cultural flowering centered there under the sponsorship of the Ashikaga Yoshimitsu 1367(8) to 1408 (he retired to the villa in 1395). Kyoto is in the center of a ring of low mountains. Yoshimitsu particularly sponsored Zen-Buddhist inspired Renga poetry, Noh theatre (see below for the section on Noh), and began the tradition of Douboushuu, i.e. curators of the Shogun’s collections. The douboushuu were hired as professional art curators, producing the first catalogues in Japan, and acting advisers on a wide range of aesthetics. Most were also practicing artists of various types -- poets, painters, noh theatre writers and performers, flower arrangers, craftsmen, architects and garden designers – and often came from outside the caste system and lived therefore as Buddhist monks (though not necessarily celibate).

- 30. Ashikaga Yoshimasa’sGinkaku (‘Silver Pavilion’) and Garden of Jisho-ji. The silver was never added to the building, which includes a spaced dedicated to the tea ceremony, and became the gathering place for many poets and artists during Yoshimasa’s retirement. He determined that upon his death it would become a Zen temple, and today it is known as “Jisho-ji”, or "Temple of Shining Mercy,” based on the Buddhist name Yoshimasa assumed when he became a Buddhist monk five years before his death in 1490; it is associated with the Shokoku-ji lineage of Rinzai Zen. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Higashiyama_Bunka Higashiyama Bunka or “The Culture of the Eastern Mountain” refers to the cultural impetus from Ashikaga Yoshimasa’s “Eastern Mountain” villa in Kyoto. Construction on the Higashiyama villa began in 1482, and Yoshimasa retired and moved there in 1483. In 1485 the Buddhist practice hall was complete, and Yoshimasa ‘took tonsure’ (shaving of the scalp) and a Buddhist name. Construction of the Silver Pavilion began in 1489 but was not completed before Yoshimasa died in 1490. During his reign and retirement, Yoshimasa sponsored numerous artists and writers, providing major contributions to theatre, poetry, architecture, gardening, the tea ceremony, and other traditions, including, for those interested, Japanese sword making. In the following sections we will look a bit more in detail at some of the arts that flourished under the Ashikaga Shoguns:

- 31. Intaigais the term for the Chinese Imperial court Hanlin Academy (est. 738 under Emperor Xuansong) style painting, from Tang through to Ming dynasties, with painters decorating court and government offices. The Northern Song academy (under Emperor Huizong 1082-1135) emphasized colorful flower and bird depictions, and the Southern Song academy (under EmeprorGaozong 1107-1185), emphasized landscapes. These groups had a major influence on Japanese landscape painting (intaisansuiga) when major Song works were imported in the late 12th and early 13th century . Interested students may consult paintings by May Yuan and Xia Guei, and such works as Emperor Huizong’sAutumn and Winter Landscapes" Shuutousansui-zu in Kyoto, Li Tang’s "Landscapes" Sansui-zu, Koutouin, Kyoto; Yan Ciping’s "Oxen" Shuuyabokugyuu-zu, Sen'okuHakkokan, Kyoto; Li Di’s "Ox and Herdboys "Sekichuukiboku-zu, Yamato Bunkakan, Liang Kai’s “Snow Landscape"Sekkeisansui-zu, Tokyo National Museum. In the early 15th century another large Chinese Imperial Academy influence came into Japan from the Zhe school, particularly affecting the landscapes of the famed Indian ink artist Sesshuu (1420-1501).

- 32. Autumn Landscape (Shukei-sansui) by Sesshu Toyo http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ink_and_wash_painting SesshūTōyō (1420 –1506), educated as a Rinzai Buddhist monk, showed early artistic talent and became the most famous ink and wash artist in Japanese history. In 1468-69 (age 48-49) he traveled to China for further study, and was recognized by the Imperial Court. He established a very successful studio upon his return to Japan, and developed a large following of painters of what came to be called the Ukoku-rin School. The medium championed by Sesshu Toyo (one in a line of Zen Buddhist artists whose tradition continued for hundreds of years afterwards), variously known in English as ink and wash, ink painting, or Indian ink painting (suibokugain Japanese), appealed particularly to the Kamakura and Muromachi military rulers and their favored Zen priests with the simple, austere qualities of representation of an immediate realism, often considered expressive of the aesthetic of sudden enlightenment (sattori) championed in the Zen tradition.

- 33. Poetry (Waka) Waka was a term coined in the Heian period to distinguish poems written in Japanese from those written in Chinese. Already in the Man’yoshu (c. 759 ce) the renga poetic form (linked verse poetry) was used, with poems using the 5-7-5 syllable style, followed by two lines of 7 syllables. By the time of the Shin KokinWakashu, the 8th of the 21 imperial anthologies of Japanese poetry (beginning with the KokinWakashu in 905 and ending with the ShinshokukokinWakashu in 1439), the renga had become a distinctively Japanese poetic style. During the Kamakura and Muromachi/Ashikaga Shogunates poetic rules (Shikimoku) were formalized. This 8th anthology, the Shin KokinWakashu, consisting of nearly 2000 poems, was commission in 1201 and published in 1205 by the retired emperor Go-Toba with a team of poets (Go-Toba, forced to abdicate by the Shogun, reigned as cloistered Emperor from 1198 till 1221). The work was structured to be read as a single sequence: for example, the Spring poems progress through the course of the season, and the Love poems progress through the initiation of the love affair to the bitter parting at the end. The poems do not rhyme in the original Japanese—rhymes were considered serious poetic faults. Perhaps the most famous and accomplished poet of this era and one of Japan’s greatest poets ever was Fujiwara no Teika, (1162-1241) who had a turbulent relationship with the Emperor Go Toba. In addition to his major poetic achievements, Teika made many high quality, very accurate copies of classics of Japanese literature in a distinctive calligraphic style. With extensive study of historical texts he recovered the lost method for pronouncing Japanese kana, allowing accurate pronunciation of earlier waka such as those in the 1st imperial anthology KokinWakashu. Teika’s style was enormously influential for hundreds of years after his death.

- 34. There is no shelter where I can rest my weary horse, and brush my laden sleeves: the Sano Ford and its fields spread over with twilight in the snow. An example of Teika’s in the yoen style ("ethereal beauty”) From Brower, Robert H. (1978), Translation of Fujiwara Teika's Hundred-Poem Sequence of the Shoji Era, 1200, Sophia University, ASIN B0006E39K8, p. 81., cited from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwara_no_teika A painting of Teika, possibly by his son, Tameie Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwara_no_Teika A manuscript in Teika's hand of "Superior Poems of our Time, showing his calligraphic style. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwara_no_Teika

- 35. Shotetsu (1381-1459) is considered the last great poet of the waka tradition (classical Japanese poetry). Like many of the famed Japanese poets of the early medieval period he received a Buddhist education, and spent most of his life in Kyoto, involved in complex ways with the Shoguns’ courts, and the competing schools of poetry. In 1432 a fire destroyed his dwelling and burnt up, by his own count, the 27,000 poems he had composed since the age of 20. He surviving works still number about 11,000, with masterworks in every genre. An example of one of his yugen("mystery and depth") poems (translation and format, Steven D. Carter, see next slide for citation), with the assigned topic preceding Shōtetsu's response: An Animal, in Spring The gloom of dusk. An ox from out in the fields comes walking my way; and along the hazy road I encounter no one.

- 36. One of Shōtetsu’s courtly love poems: The Unbearable Wait for Love Past and gone now is the time I awaited, leaving me clinging- anxious for wind from the pines, like dewdrops at break of day. An allusive variation on a poem by Teika: Forgotten love I had forgotten- as I kept on forgetting to remind myself that those who vow to forget are the ones who can't forget. Source: Carter (1997), Unforgotten Dreams: Poems by the Zen Monk Shōtetsu, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231105762, quoted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shotetsu

- 37. Sōgi (1421-1502) was perhaps the greatest of the renga poets, renga being the unique Japanese tradition of collaborative, linked poetry, where one poet composes a verse, then the next poet composes another verse linked in theme and language. The opening stanza of the renga was called the hokku, and became the basis of later haiku, the form now known globally. Sogi’s total output was over 90 anthologies of poetry, poetry manuals and critiques, diaries, etc. A typical renga was 100 verses in the 15th century, and these were composed by samurai, courtiers, commoners, rulers, whomever was good at poetry. These poetic compositions were ‘live,’ i.e. done on the spot, one person after another. The most famous work in all the renga canon was “Three Poets at Minase” (Minasesangihyakuin) composed on the 22nd day of the first month of 1488 by Sogi, age 64, and his two senior and already very famous students Shohaku, and Socho, at Yamazaki, across the river Minase from the site of Emperor Go-Toba’s palace, their renga composed in honor of the very same emperor who had directed the compilation of the Shinkokinshufrom 1201 to 1205. (see Carter, S.D., Three Poets at Yuyama, Sogi and YuyamaSanginHyakuin 1491, MonumentaNipponica 33,3, Autumn 1978, pp. 241-283). The same three poets gathered 4 years later to compose another, less solemn renga, which also became one of the most famous of all time, the "Three Poets at Yuyama" (Yuyamasanginhyakuin, 1491). Following is a translation of some of the first ten linked verses, extracted from Steven D. Carter’s article:

- 38. 1 On the mountain path The leaves lie rich-colored Under a thin snow. SHOHAKU 2 Miscanthus at the crag's base- In winter a still greater delight. SOCHO [Note: Miscanthus is a perennial grass] The ‘waki’ or second verse is intended to act as a host would towards a guest, the hokku or first verse—here with the grass at the base of the mountain in the hokku verse. 3. By a pine cricket First lured forth, I left my dwelling. SOGI 4. The night has grown late- A fall wind blows my sleeves. SHOHAKU 5. So cold is the dew- Even the light of the moon Seems transformed. Socho 6. Unfamiliar fields I cross, Unsure of my direction. SOGI 1 (hokku) Usuyukini Konohairokoki Yamaji kana. 2 (waki) Iwamoto susuki Fuyuyanao min 3 (daisan) Matsumushini Sasowaresomeshi Yadoidete. 4 (daishi) Sayofukekerina Sode no akikaze. 5 Tsuyusamushi Tsuki mo hikariya Kawaruran. 6 Omoi mo narenu Nobenoyukusue.

- 39. 7 Katarau mo Hakana no tomoya Tabi no sora. 8 Kumooshirube no Mine no harukesa. 9 Ukiwatada Toriourayamu Hananareya. 10 Mi onasabaya Asayu no haru. (Source: Carter, S.D., Three Poets at Yuyama, Sogi and YuyamaSanginHyakuin 1491, MonumentaNipponica 33, 3, Autumn 1978, pp. 248-253). 7. We share a few words, But friendships are fleeting Under skies of travel. SHOHAKU 8. So distant is the peak- I take the clouds as guides. SOCHO 9. My sadness is due To the sight of those flowers: How we envy the birds! Sogi 10. If only I could transform myself, Now that the spring has come.Shohaku

- 40. Nou/No/Noh developed as a serious, Buddhism-infused theatrical art form from the earlier more diverse and lively Chinese sarugaku 'monkey music'. Slow, ritualized movements of only 2 or 3 actors in magnificent costumes, the lead often wearing a lightweight cedar-wood mask, take place (still today!) on a bare, square stage with minimal props, backed by a chorus of 6-8 singers, whose recitations interweave with the dialogue, and a few musicians playing a flute and two or three types of percussion. Perhaps the most famous figure in the history of No theatre was ZeamiMotokiyo (1363 – 1443). He (at age 12) and his father Kan’ami – a renowned performer, caught the attention of the 17 year old Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu during a provincial performance. Yoshimitsu offered to sponsor them, bringing them to the capital. Under Yoshimitsu’s guidance, Kan’ami and Zeami refined sarugaka and the traditional Japanese dance dengaku (plus a variety of other indigenous performance arts) into a form appropriate for Buddhist temples and shrines, with the Noh performances designed to evoke among the audience reflections on Buddhist ideals and philosophy. Zeami himself wrote over 50 plays, many of which are among the 240 still performed, and his father dictated to him the classic of Noh instruction, Fushikaden (finished in 1418), which is still used by Noh performers today. Zeami’s introduction to the Fushikaden ascribes an Indian origin of the No, asserting the plays were first performed in Buddha’s time, at Buddha’s suggestion, to bring peace to the populace and help propagate his teaching—a reverent fiction that has no historical basis, but is related to Zeami’s other report that Prince-Regent Shotoku’s (573-621) command to Hata no Kokatsu to create public entertainment for the sake of national peace. The chapters lay out stages of training from age 6 to 50, prohibitions against sexual pleasure, gambling, and heavy drinking; they detail monomane, the imitation by the main actor (when wearing masks) of roles of women, old men, mad persons, Buddhist priests, dead warriors, gods, demons, and Chinese characters. Yin-yang harmonization in performance is examined, including understanding the distinction between the passing flower of youth and the true flower (hana) of maturity. The tradition is explained as the passing down of No from the first instance of a sagaraku dance in age of gods by goddess Uzume in front of heavenly cave where Sun Goddess Amaterasu had hidden herself (this being the Shinto origin myth of the Japanese people). True mastery of Noh is explained as mastery of both Omi style (which emphasizes the Japanese aesthetic ideal of yugen ‘that which lies beneath the surface’) and Yamato style (which emphasizes monomane). The purpose of No is to bring long life and prosperity and happiness for everyone, regardless of their social standing; a true master can mix styles to accomplish this with any audience.

- 41. Between acts in the Noh plays there is traditionally performed a bit of a comedy skit, known in the tradition as Kyogen (a comedic, fictional, or nonsense story), and dating back at least to the Nara period (710-784). As in Noh the stage is left bare, with no more than 2-4 actors involved. “One famous Kyogen story is called 'CHATSUBO', which is a large jar or tea pot. There is a man drunk and sleeping on the street. The shite [main actor], named Suppa, comes across the man and wants to steal the tea jar. The problem is that the man carries the jar like a backpack and even though he is passed out, he has his right arm through the one strap. Suppa thinks for a while and then lays down next to the man and puts his left arm through the other strap. When the man awakes, Suppa declares that the tea jar is his and an argument ensues. The drunk calls a sheriff and explains the situation, but Suppa firmly duplicates his story to the sheriff too. So, the sheriff is unable to decide who it is. Then the sheriff declares that in his district when two people have equal claim to an item, then a third person should take it. He then takes the tea jar and leaves, while being chased by Suppa and the drunk.” Source: http://shofulpref.ishikawa.jp/shofu/geinou_e/nougaku/index_e.html

- 42. The masks used in Noh plays are an art form unto themselves. They are ingeniously designed so that depending on the tilt of the actor’s head, the face can appear to have happy, sad, puzzled, or many other types of expressions, as the light will bounce differently off of the mouth and eyes. Noh mask Source: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Noh Noh mask source: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Noh

- 43. For English translations with Japanese text and notes of 13 Noh plays, see http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/noh/index.html For more details see: http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/n/nou.htm http://www.japan-zone.com/culture/noh.shtml Benito Ortolani,The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism. Volume 1, pp. 108-111, Handbuch der Orientalistik. Fünfte Abteilung, Japan, 2. Bd., Theater, 1. AbschnittHandbüch der Orientalistik. Bd. 2, Theater, 1. Abschnitt, Brill 1990 And the links provided in the Wikipedia and New World Encyclopedia entries. Noh Stage http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Noh Noh play at Itsukushima Shrine http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Zeami_Motokiyo ;

- 44. The Tea Ceremony (Sado): as mentioned above, Buddhist monk Eisai (1141-1215) brought cake tea and its preparation method back from China. The tea grown near Kyoto from Eisai’s seeds was considered the best in the country, and court tea tasting parties developed where prizes were given for the person who could guess which cup of tea was from those plants. The Buddhist character of the tea drinking culture was strongly influenced by polymath Chinese author Lu Yu’s “The Classic of Tea” (760-780 ce), a practical work on the arts of how to grow, process, and drink tea, and the product of several decades of careful research on tea in China, covering the art and culture of tea, its history and agronomy (botany, biology, farming methods, water requirements), and the proper implements for ensuring optimal tea production and drinking. Lu Yu argued against the practice of drinking tea mixed with other ingredients, asserting that pure, unadulterated tea was the only way the beverage should be drunk – a custom followed by Chinese and Japanese to this day. The tea ceremony in Japan was developed with an aesthetic of inner personal transformation. Ashikaga Yoshimasa is credited arranging for the first-ever dedicated tea room to be built at his villa in 1486, designed by his tea master Murata Shuko(1423-1503) and known as the Dojin-sai, which became the model for those that followed -- a room fitted with staggered shelves (chigaidana), a decorative alcove (tokonoma) and tatami mats, and a built in table (tsukeshoin). Gardening: The art of gardening at temples, palaces, and in miniature form in bonsai and bonseki, while long in development in Japan, saw some major contributions during the Ashikaga era, with Shogun-employed polymath garden designers who were variously also poets, artists, Zen priests, architects, and performing artists. KokanShiren 1278-1347, a Rinzai Zen priest and famed Chinese language poet, who wrote the Rhymeprose on a Miniature Landscape Garden, exploring the aesthetics of bonsai, the Japanese garden, and the miniaturized landscapes of bonseki. The following is an excerpt from the Rhymeprose (Saihokushu, ch. 1, pp. 1-2.), when Shiren challenges a visitor to appreciate a miniature garden he has been developing: “Another thing, do you think this miniature landscape is big? Do you think it is small? I will blow on the water and raise up billows from the four seas. I will water the peak and send down a torrent from the ninth heaven! The person who waters the stones sets the cosmos in order. The one who changes the water turns the whole sea upside down. Those are the changes in nature which attain a oneness in my mind. Anyway, the relative size of things is an uncertain business. Why, there is a vast plain on a fly’s eyelash and whole nations in a snail’s horn, a Chinese philosopher has told us. Well what do you think?” source http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kokan_Shiren Flower Arrangement (Ikebana): The tradition of placing flowers in temples to honor images of the Buddha had a long history in Asia and came to Japan with Buddhism. The beginning of the particular Japanese tradition of flower arrangement as a simple yet elegant and sophisticated art form is credited to the 15th century Buddhist priest IkenoboSenkei of the Rokkakudo Temple in Kyoto. He evidently had great skill in flower arrangement, was sought out by other Buddhist priests and began what is now an over 500 year old tradition.

- 45. This Unit has provided a very brief introduction to the deep, complex and rich classical culture of Japan. Most of the cultural traditions in the arts and literature and religion have continued into contemporary times. We have in the time up to 1500 the establishment and development of most of the essential elements that characterize traditional Japanese culture. While this unit is necessarily brief, each of the topics covered can be explored in far greater depth than what is presented here. We close this unit with some remarks by Prof. Rimer of U. Pittsburgh and the 14th century Japanese author Yoshida Kenko. Students are referred to the Japanese Text Initiative Website cited below, a collaboration between the University of Virginia and the University of Pittsburgh : “In his 14th century classic, the Tsurezuregusa ("Essays in Idleness"), Yoshida Kenko, the author, writes that [in Donald Keene's elegant translation] "...the pleasantest of all diversions is to sit alone under the lamp, a book spread out before you, and to make friends with people of the distant past you have never known." The principle he stated so well here remains the same; but although we still need the lamp he spoke of, some find that the book has now given over pride of place to the computer. Used wisely, these new and expanded possibilities can make the world of the past ever more accessible, and ever closer to us.” Thomas Rimer University of Pittsburgh Pittsburgh, PA http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/jti.intro.html