Rethinking the Peripheral: A Study of Chinese Migrants in Lesotho

- 1. Rethinking the Peripheral: A Study of Chinese Migrants in Lesotho 对‘边缘’ 的再思考——中国人在莱索托 Naa bohole bo etsa phapang?: Balakolako ba kojoana li mahetleng ba Machaena matsoatlareng a Lesotho. 1

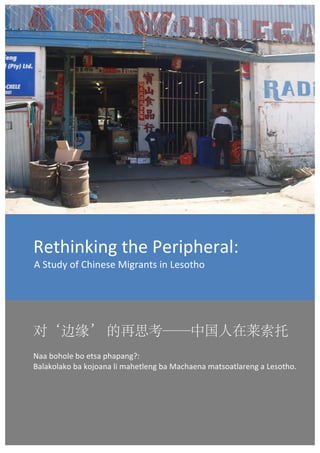

- 2. Statement This is my own unaided work and does not exceed 20,000 words. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Wolfson College for their financial contribution to my research costs. I would like to thank Mr. Lin for his invaluable assistance during my fieldwork and for helping me to overcome many of the practical difficulties involved in my research. A final thanks to Dr. Xiang Biao for his input and warm encouragement at all stages of the development of this thesis. Cover Image: A Chinese-‐owned food wholesaler in Maseru. Source: Author’s Own, 2010. 2

- 3. Contents List of Figures.....................................................................................................................4 Clarification of Terms and Acronyms..................................................................................4 Preface ..............................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1. Introduction......................................................................................................8 1.1 Rethinking the Peripheral...........................................................................................8 1.2 The Research Site ....................................................................................................12 Chapter 2. A Review of Literature on China’s Engagement with Africa..............................17 Chapter 3. Methodology ..................................................................................................29 3.1 The Ethnographic Approach .....................................................................................29 3.2 The Fieldwork..........................................................................................................30 3.3 Gaining Access.........................................................................................................31 3.4 The Interviews.........................................................................................................33 Chapter 4. Findings and Discussion...................................................................................38 4.1 Lesotho’s Established Chinese Communities.............................................................38 4.2 From Fujian to Lesotho: Periphery-‐to-‐Periphery Migration .......................................47 4.3 Understanding Fujianese Modes of Mobility.............................................................54 4.4 Making the Periphery Profitable...............................................................................57 4.5 Sino-‐African Relations at the Periphery ....................................................................66 4.6 New Directions? ......................................................................................................70 Chapter 5. Conclusions.....................................................................................................73 Bibliography.....................................................................................................................79 3

- 4. List of Figures Figure 1: Map of Lesotho ....................................................................................................... 13 Clarification of terms and acronyms Basotho Plural demonym for the South Sotho people (sing. Mosotho). The Basotho live chiefly in Lesotho. ALAFA Apparel Lesotho Alliance to Fight AIDS BCP Basutoland Congress Party EDF European Development Fund FSB Fujian Statistics Bureau GDP Gross Domestic Product PRC People’s Republic of China ROC Republic of China (Taiwan) 4

- 5. Preface The reforms initiated in China in 1978 have had a monumental impact on the mobility of Chinese people, both nationally and internationally. According to Murphy, the over 100 million itinerant labourers and traders who have left their native homes in search of work in China’s cities represent ‘the largest peacetime movement of people in history’ (Murphy, 2002, p. 1). In addition to paving the way for internal migration, the reforms have created unprecedented opportunities for outmigration from the Chinese mainland, allowing a new generation of Chinese migrants to seek their fortunes overseas. Even in this new era of frenzied interest in China, studies of the overseas Chinese have focused on the older and better-‐known Chinese migrant communities of North America, more recently Europe (see: Avenarius, 2007; Beck, 2007; Pieke et al., 2004, p.2; Pieke & Xiang, 2009; Skeldon, 2000; Thunø et al., 2005). In general, writings on Chinese transnational migration have tended to assume that the United States and the wealthy countries of Western Europe are every migrant’s destinations of choice. Other destinations are imagined to be second best, or stepping stones on longer trajectories of mobility (ibid., p. 3). This focus on migration to the centres of the global economy ignores the fact that most transnational movements of persons, including Chinese migration take people to places ‘that seem, at first glance, curiously nonobvious’ (Pieke et al., 2004, p. 3). For instance, studies of Chinese migration have almost entirely overlooked the 5

- 6. fact that in the past decade, more than a million Chinese people, from chefs to engineers, are thought to have moved to work in Africa (Rice, 2011). Far from being limited to Africa’s urban centres, the effects of Chinese migration have been felt even in the most remote corners of the continent. This investigation seeks to redress the imbalance in the scholarship around this issue by focusing on migration between different sites in the global periphery. Throughout my analysis, I use the term ‘periphery’ to refer to those real places that are outside the flows of goods, capital and persons that converge on global centres such as New York, London and Tokyo. These out-‐of-‐the-‐way places constitute sites of exclusion in the global economic system and have traditionally been assumed to offer little in the way of opportunities for accumulation and capital generation. Lesotho’s highland villages are a textbook example of this kind of periphery, and yet they have become a popular destination for a particular class of merchants from Fujian province. These traders have succeeded in establishing a retail stronghold in Lesotho, penetrating corners of the country previously unreached by foreign businesses. This paper is premised on a desire to discover how and why Lesotho’s Fujianese migrant communities become established at these marginalised sites. I was keen to discover the aspirations of Fujianese migrants in coming to Lesotho and to identify the specific factors that influenced their decision to migrate. Furthermore, I wanted to understand how they perceive the ‘remoteness’ and ‘peripherality’ of Lesotho’s mountainous hinterland and to discern the strategies 6

- 7. and practices that allow them to turn the periphery into a productive space. In carrying out this research, I hoped to be able to redress the relative paucity of ethnographic research on the Chinese diaspora in Africa, particularly in small, resource-‐poor nations such as Lesotho. In the first chapter, I seek to unpack the construction of ‘marginality’ in the context of different theories of ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ emerging from international political economy. I suggest that Fujianese migrants, who are themselves a peripheral group in the world system, may perceive the periphery in distinct ways . This chapter also provides an overview of Lesotho’s economic situation and its particular history as a peripheral enclave surrounded by South Africa. In the second chapter, I provide a critique of the existing literature on Sino-‐African relations, arguing that most writings on Chinese activity in Africa have provided top-‐down accounts of Beijing’s dealings, ignoring the important but complex role played by the Chinese diaspora in transforming the continent. Chapter three provides an account of the research methods and mode of analysis adopted for this investigation. The findings of my investigation are discussed in chapter four and summarised in chapter five. 7

- 8. Chapter 1. Introduction 1.1 Rethinking the Periphery The notion of ‘periphery’ provides us with a structural orientation for understanding spatialised patterns of inequality and exclusion. Although peripheral places are geographically diverse, they share a number of common characteristics that set them diametrically apart from those places at the ‘centre’ of global systems. These places often enjoy limited access to flows of goods, capitals and persons and are subsequently placed outside major transnational networks of trade and migration. Indeed, many scholarly narratives of migration are underpinned, explicitly or implicitly, by an assumption about a divide between ‘traditional peripheries’ and ‘modern centres’. Being located outside global trade and knowledge networks, peripheral regions are typically unable to develop the kinds of industry and capital base required to achieve economic takeoff and ‘modernisation’. By contrast, regions at the core concentrate transnational flows and typically allow for rapid rates of capital accumulation and technical innovation. Modernisation theorists have long posited that migration from periphery to core and return flows from core to periphery play a vital role in making ‘traditional’ societies more ‘modern’, thus ‘developing’ the periphery (Goldscheider, 1987, pp. 677-‐80). By contrast, structuralist theories have argued that migration cannot improve the situation of the periphery because it consolidates an unequal 8

- 9. relationship of dependence with the core. Instead, structuralist studies have suggested that migration has a negative impact on peripheral regions, locking traditional communities into poverty and cementing traditional power structures (Colton, 1993, pp. 870-‐82). Dependency theory proposes a very different understanding of the relationship between the core and the periphery, but nevertheless it holds the core-‐ periphery divide to be a central feature of the world society. Dependency theorists have posited that societies are inextricably linked, within a global system, through relationships of dependence. They reject the idea that developing countries lag behind the developing world, arguing instead that both developed and developing countries are at the same historical stage. They suggest that the developed world is at the core of the world system and the developing world is at the periphery. Core and periphery thus constitute two sides of the same coin, with the poverty of the latter being a prerequisite for the prosperity of the former (Frank, 1967; Dos Santos, 1971; Amin, 1976). World systems theory has proposed a similar but more nuanced model of ‘dependency’ or ‘reliance’ between the core and the periphery. Whereas ‘dependency’ in Dependency theory is unidirectional, ‘reliance’ in World systems theory is bidirectional, operating within a three-‐tier framework. This framework posits the existence of a third category: semi-‐peripheral places, which exist between the core and the periphery proper. This sliding model differs significantly from the binary conception of core dependency on the periphery in that it suggests that a 9

- 10. circulation of powers is an unavoidable outcome of the system. In other words, a semi-‐peripheral region may displace a core region in decline, thus moving from the periphery to the core (Wallerstein, 1976). In any case, regardless of which notion of peripherality one subscribes to, it is clear that both the core and the periphery are increasingly linked by the processes of globalisation. I use this term to refer not to a unidirectional tendency, but rather to a multitude of processes ‘that transcend and redefine regional and national boundaries’ (Pieke et al., 2004, p. 9). These processes produce a world that is increasingly interconnected, rearranging spaces of flows and challenging established notions of marginality and periphery. In doing this, globalisation produces a ‘new reality’, creating new social forms and inflecting existing social forms ‘such as the nation-‐state, the family, class, race, or ethnicity’ (ibid.). Crucially, the scope of globalisation extends ‘beyond the traditional centres of the capitalist system’ (Pieke et al. 2004, p. 10). That is to say, globalisation reconfigures spaces within and beyond the established centres of the world economy. In facilitating new flows of capital, technology and migration, globalisation creates contingent and dynamic relationships between ‘multiple centres and peripheries’ (ibid.). Of particular interest for this investigation is the way in which globalisation creates connections between places previously considered to be on the fringes of hegemonic geographies of flows. 10

- 11. Notions of dependency and reliance have laid the foundation for popular understandings of national and transnational mobility. These interpretations, emerging from the field of development studies and intended to inform development policy, have been critiqued by Murphy for being too Manichean and simplistic for understanding the complexities of change in the global economy (Murphy, 2002, p. 18). They certainly fall short in terms of explaining the numerous contingent and context-‐specific factors that may influence an individual’s decision to migrate. Indeed, macroeconomic models such as these leave little room for an appreciation of the agency of the individual and an understanding of the interactions of social and economic pressures, which inflect that agency. It became clear to me, while reading around this topic, that the changing nature of Chinese migration required in-‐situ investigation of Chinese communities outside China. How and why these communities become established in developing countries are important and relatively unexplored questions within contemporary social anthropology and migration studies. This is a particularly interesting area of study given that, contrary to the narratives promulgated in Western media accounts of international migration, most mobility of people takes place ‘between peripheral areas rather than from a periphery to a centre’ (Pieke et al., 2004, p.198). Indeed, Xiang states that, within the destination countries, most Chinese migrants work in remote areas instead of major cities (Xiang, 2009, p. 421). According to Pieke and his team, the nature of this mobility cannot be truly appreciated from the centre, hence the conspicuous lack of writings produced on 11

- 12. this subject by Western scholars (ibid.). This is because the enduring influence of the centre-‐periphery dichotomy is part of a paradigm that tends to view migration and return flows as phenomena that are external to peripheries (Murphy, 2002, p. 17). Pieke et al. go on to explain that, for Chinese migrants, ‘the map of the world looks distinctly different from what we ourselves would assume, with centres and peripheries in some unexpected places’ (Pieke et al., 2004, p. 3). Indeed, this paper is premised on a desire to rethink the peripheral and to view the world from the migrant’s perspective. That is not to say that I assume that migrants do not perceive ‘periphery’ as a real spatial category but rather, that they approach the periphery in a certain way that allows them to thrive where others have previously struggled. 1.2 The Research Site Lesotho is one of many African countries that have been entirely neglected by scholarship on Chinese migration to Africa. With a population of just over two million people (World Bank, 2009) and a total land-‐area of approximately 30,355 km2 (roughly the size of Belgium or Taiwan), the Mountain Kingdom is completely surrounded by South Africa, the continent’s most developed country. Lesotho is classified by the UN as a ‘least developed country’ and, with a GDP per capita of $764, the kingdom is ranked 156th on the human development index (World Bank, 2009). In short, Lesotho occupies a position within conventional imagined geographies of development that is undeniably peripheral. 12

- 13. Figure 1: Map of Lesotho Source: Mapsget, 2011: http://www.mapsget.com/bigmaps/africa/lesotho_pol90.jpg Lesotho’s peripherality is, in part, a product of its relative poverty compared to its wealthier neighbour, South Africa – a country that is increasingly seeking to assert itself as a regional hub of transnational flows. Turner identifies three 13

- 14. intermediate causes of poverty in Lesotho. These are unemployment ‘linked to the heavy retrenchments of Basotho migrant labour from the South African mines over the last decade’ (Turner, 2005, p. 5), environmental problems such as ‘frosts, drought and floods’ (ibid.), and HIV/AIDS, which he describes as ‘both a cause and a symptom of poverty’ (ibid.). Lesotho currently has the third highest adult HIV prevalence in the world at 23.3% (ALAFA, 2008) and the pandemic continues to be a source of ‘enormous hardship, and death, for rapidly growing numbers of people’ (Turner, 2005, p. 6). In addition to these intermediate causes of poverty, Lesotho’s peripheral position within Southern Africa is perpetuated by its history as a labour reserve for South Africa, its prevalent gender inequality and its record of inefficient governance (Turner, 2005 p. 5). Low fiscal incomes and an over-‐bureaucratised state have meant that poverty-‐reduction initiatives in Lesotho frequently fail in the implementation stage. The country has long been a recipient of foreign aid but, in the words of one development analyst, the history of foreign aid projects in Lesotho has been one of ‘almost unremitting failure’ (Murray 1981, pg. 19 in Ferguson 1990, pg. 8). Lesotho has virtually no natural resources other than water, which it exports to South Africa. Consequently, the country suffers from a large trade deficit, with exports representing only a small proportion of total imports. These factors have cemented Lesotho’s position at the margins of the global economic system. This economic marginalisation is complemented by cultural marginalisation at the 14

- 15. international level, with little attention being given to Lesotho by the international media. Estimates of the total population of Mainland Chinese currently settled in Lesotho range from five to twenty thousand. This is a relatively small community compared to the populations of settled Chinese in the United States or even in other African countries and, as a result, Lesotho’s Chinese have been entirely neglected by academic scholarship. My research has shown that the majority of the Chinese living in Lesotho are low-‐skilled economic migrants from Fujian province, a major site of Chinese emigration (Pieke et al., 2004). Early flows of Indian and skilled-‐Chinese migration to Lesotho have, since 1998, been eclipsed by the comparatively vast influx of poorly-‐skilled migrants from Fujian’s rural interior. This new group of migrants has established a retail hegemony in Lesotho, penetrating corners of the country previously unreached by either local or foreign businesses. The present flow of Fujianese migration to Lesotho appears to have followed in the wake of earlier flows of Taiwanese and Shanghainese migration to the country, suggesting that migration to the periphery is not sustainable, in the long term, by migrants from a single region. My research demonstrates that the Fujianese in Lesotho approach the country’s mountainous margins with a set of strategies that allow them to cultivate the periphery as a prime site for capital accumulation. These strategies include group purchase and transport of goods and targeted pricing campaigns against local 15

- 16. competitors. Given the small numbers of buyers in remote areas, Fujianese traders are reliant on captive markets for the profitability of their enterprises. The need to establish a small monopoly over a given resource in a given area produces a centrifugal force that continuously pushes new arrivals from Fujian further and further into Lesotho’s periphery. 16

- 17. Chapter 2. A Review of Literature on China’s Engagement with Africa There has, in recent years, been an explosion of interest in ‘China and Africa’. While the socio-‐economic changes brought about by China’s reforms and rapid economic ascendancy have, for some time, been a focus for scholarly interest, it is only in the last two decades that China’s engagement with Africa has come under academic scrutiny. This recent scholarship on ‘China and Africa’ has focused almost exclusively on the geopolitical implications of China’s activities in Africa. In reviewing the recent body of literature on Sino-‐African relations I hope to demonstrate the extent to which the majority of these writings present top-‐down, macro-‐scale narratives of Chinese engagement with African countries. By contrast, there is a conspicuous dearth of ethnographic studies of the Chinese diaspora in Africa and the migratory trajectories that have brought them to even the most remote corners of the continent. This paper is intended to help redress this gap since, as Alden rightly explains, ‘for most ordinary Africans it is these Chinese small-‐scale entrepreneurs, and most especially retail traders, who have had the greatest impact on their lives’ (2007, p. 37). It is easy to see why the geopolitics of Sino-‐African relations has recently become a ‘hot’ topic amongst academics from a wide range of disciplines. There is a sense in the literature that the academic community was caught off-‐guard by China’s sudden (re)intensification of its relationships with African governments. The Chinese Communist Party strongly denies claims that its interests in Africa are 17

- 18. opportunistic and instead propounds a discourse of ‘ongoing partnership’ with the African peoples, dating as far back as the 15th century (Alden & Alves, 2008, p. 43). However, in spite of the warm Communist rhetoric, there have been clear fluctuations in the intensity of China’s African diplomacy, at least over the last sixty years. Writings published in English during the last decade by African, European and American scholars on China’s engagement with Africa have tended to emphasise the materialistic dimension of China’s relationships with African governments (Alves, 2008; Ennes Ferreira, 2008; Kragelund, 2007; Soares de Oliveira, 2008). However, during the Mao years (1949-‐1976), the emphasis of China’s African diplomacy was unmistakably ideological. Indeed, according to He, it was the Bandung Conference of 1955 that set the precedent for the future of Sino-‐African relations (He, 2008, p. 147). Alden & Alves argue that the ‘South-‐South solidarity’ expressed in the Non-‐ Aligned movement persists to this day in China’s strictly bilateral approach and emphasis on ‘mutual benefit’ (Alden & Alves, 2008, p. 47). However, despite this politicised language, there was clearly a dilution of the ideological pro-‐activism of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai during the first decade under Deng Xiaoping (1978–1989) (Alden et al., 2008, p. 5). Following the 1978 reforms, Beijing has tended to avoid overtly political discourse in its dealings with foreign governments and instead placed a greater emphasis on economic co-‐operation (Power & Mohan, 2008b, p. 26). 18

- 19. The latest surge in scholarship on ‘China and Africa’ has been in response to the stepping-‐up of Sino-‐African relations in the wake of the Tiananmen Square uprisings of 1989, which left Beijing in desperate need of political allies. The subsequent rapprochement between the party-‐state and African governments has been consolidated, in economic terms, by the ‘Go Out’ policy (走出去战略)of 1999, which has set the tone for more proactive overseas investment by Chinese companies. It is clear from the scholarly literature produced outside China over the last two decades that China’s ’going out’ to Africa has become a cause for real concern amongst many who have traditionally imagined Africa as being part of a peripheral space at the hinterland of Western economic empires. That is to say that the majority of scholarship on ‘China and Africa’ appears to be written in response to China’s perceived threat to the geopolitical status-‐quo rather than in response to real changes happening on the ground as a result of interactions between Chinese and African communities. In an insightful review of representations of Sino-‐African relations in British broadsheet newspapers, Mawdsley (2008) identifies a number of recurring discursive patterns that pervade reporting on China’s activity on the African continent. I intend to borrow Mawdsley’s rubric as a starting point from which to frame my own discussion of the academic literature surrounding contemporary China-‐Africa relations. Mawdsley’s critique highlights a number of characteristics, which define recent scholarly accounts of China’s engagement with Africa. In each 19

- 20. case, these characteristics are the result of a decided preference for top-‐down appraisals of China’s presence in Africa and a failure to understand the significance of this presence from the perspective of the Chinese who have made their livelihoods there. The first trend identified by Mawdsley in her review of British reporting on Sino-‐African relations is the tendency to conflate non-‐Western actors in accounts of engagement between ‘China’ and ‘Africa’. I use inverted commas to highlight the need to disaggregate ‘China’ and ‘Africa’ since, as some have rightly pointed out, ‘neither represents a coherent and uniform set of motivations and opportunities’ (Power & Mohan, 2008b, p. 19). Even within academic writing, there is a widespread tendency to refer to ‘the Chinese’ in Africa, despite the fact that this designation encompasses a huge range of different actors often with ‘competing and contradictory interests’ (Mawdsley, 2007, p. 406). Conflated within this category are numerous governmental and non-‐governmental bodies, private and state-‐owned enterprises as well as diverse settled populations of Chinese across Africa. Indeed, there is a tendency to speak of ‘China’ and ‘Africa’ ‘as if there were relationships between two countries instead of between one & fifty-‐three’ (Chan, 2007, p. 2, in Power & Mohan, 2008b, p. 34). While Mawdsley is right to be critical of writing which collapses the interests of ‘the Chinese’ into a single category, there is just as much scope for criticism of those who conflate ‘Africa’ and African actors. Accounts of Chinese dealings with ‘Africans’ suggest an undifferentiated and nebulous population of natives passively enduring exploitation by ‘China’ and ‘the 20

- 21. West’. This trend manifests itself most frequently in accounts that lump African countries together and speak of ‘Africa’ in its continental, rather than its political configurations. In refusing to acknowledge complexity and multiplicity of African actors, these accounts highlight Africa’s peripherality as a vast yet marginalised space at the fringes of the world economy. Mawdsley’s second observation in her study of British journalism is a decided preference amongst British journalists for focusing on the negative aspects of China’s engagement with Africa (Mawdsley, 2008, p. 518). In the context of academic writing, I intend to break down this point into two criticisms. Firstly, a criticism of those academic writings which frame ‘China’ as a ‘dragon’ or ‘ravenous beast’ and secondly, a criticism of those academics who choose to focus solely on ‘issues and places of violence, disorder and corruption’ (ibid.), and within that on the P.R.C.’s engagement with odious regimes and resource-‐rich countries in Africa. The image of China as a dragon or rampant leviathan is a discursive pattern that pre-‐dates the recent intensification of China’s economic relations with African governments. It reflects the genuine apprehension felt by many in ‘the West’ in the face of China’s accelerated economic development and increasingly important role in the geopolitical arena. In the context of recent activity in Africa, China is frequently described in academic writing as ‘a monolithic beast with an insatiable appetite for African resources’ (Power & Mohan, 2008b, p. 22). This discourse simultaneously reinforces negative narratives of Chinese economic development and reproduces narratives that construct ‘Africa’ as a marginalised space of plunder 21

- 22. within a binary scenario of exploitation by major economic powers. In the following passage we see an extreme example of this kind of writing: In just a few years, the People's Republic of China (P.R.C.) has become the most aggressive investor-‐nation in Africa. This commercial invasion is without question the most important development in the sub-‐Sahara since the end of the Cold War -‐-‐ an epic, almost primal propulsion that is redrawing the global economic map. One former U.S. assistant secretary of state has called it a "tsunami." Some are even calling the region "ChinAfrica"(Behar, 2008, p. 1). Writing such as this serves to perpetuate narratives that construct China’s presence in Africa as a ‘scramble’, ‘mad dash’, ‘resource grab’, or even a ‘rape’(Power & Mohan, 2008b, p. 24). Criticisms of China’s interest in African natural resources are often voiced explicitly by those who firmly believe that Chinese investment in Africa is part of a long-‐term strategy to control and exploit African natural resources, particularly oil (Askouri, 2007, p. 72). Often, China is portrayed not only as a pillager of African resources but also as a direct competitor in those industries that are seen as key to Africa’s development. Here, China’s presence in Africa, like America’s presence before it, is regarded as problematic because it is thought to undermine the autonomy of African societies through forms of imperialism that transcend the nation state (Hardt & Negri, 2000 and Johnson, 2004): The undermining of manufacturing in Sub-‐Saharan Africa as a consequence of Asian Driver competition in SSA and external markets is likely to lead to increased unemployment, at least in the short run, and heightened levels of poverty (Kaplinsky, Robinson, & Willenbockel, 2007, p. 25) 22

- 23. China’s presence is also considered to be detrimental to the pursuit of developmental sustainability in Africa because of its disregard for good governance. Within the body of recent academic writing on China’s engagement with Africa, we can also identify a distinct preference for accounts of China’s dealings in resource rich countries (Alves, 2008, Ennes Ferreira, 2008, Kragelund, 2007, Power, 2008, Soares de Oliveira, 2008) and those countries where China appears to be supporting odious regimes (Askouri, 2007, Karumbidza, 2007, Large, 2008a, Tull, 2008). This tendency is a clear manifestation of the desire, within the non-‐Chinese academic community, to highlight the negative aspects of China’s ‘Going out’ to Africa. The positive elements of Chinese activity in Africa, including debt cancellation, investment, commodity price impacts and support for a greater international voice, are ignored in favour of a focus on problem issues (Mawdsley, 2008, p. 518). This concern with China’s negative impacts on the continent is concurrent with a postmodern discourse that is inherently suspicious of global economic powers and, as such, fails to recognise the significance of day-‐to-‐day interactions between Chinese and African people. One notable outcome of the predominantly macro-‐ level portrayal of China-‐ Africa relations is a strongly biased interpretation of the role of Africans in these interactions. Accounts of China’s activity in Africa regularly portray Africans either as ‘victims’ or ‘villains’ (Mawdsley, 2008, p. 518) , and sometimes as both, thus endorsing images of a politically impotent African population, perpetually at the mercy of foreign powers and corrupt leaders. As Mawdsley stresses in her last 23

- 24. criticism of British journalism on Sino-‐African relations, the intensity of this focus on China as a new threat to African prosperity leaves room for little more than a ‘complacent account’ of the West and its past and present dealings with African peoples. Within this uncritical narrative, Chinese activity in Africa is negatively contrasted against Europe’s historical forays into the continent. As Mawdsley explains, ‘Western colonialisism is claimed to at least have had a paternalistic/developmental dimension and well-‐intentioned elements -‐ an attitude that has translated into an ethical concern for Africa in the postcolonial period’ (Mawdsley, 2008, p. 519). The implication is therefore that Europe and the U.S. have moved on to a more enlightened concern for Africa. This concern implies moral superiority over any Chinese interests on the continent, which are assumed to be purely opportunistic. This configuration constructs the Chinese state as potent force of chaos in the African context. It is clear from numerous writings (Bräutigam, 2008b; Campbell, 2007; Gill, Morrison, & Huang, 2008; Marchal, 2008) that there is considerable concern, amongst African, European and American academics, regarding Beijing’s recent foreign policy towards Africa. Criticisms of China’s dealings with African governments arguably reflect a broader concern that China represents a chaotic force which seeks to undermine Western efforts to promote good governance, global security and debt sustainability in Africa. I will examine each of these points in turn, concluding that these simplistic representations ignore the complexity of 24

- 25. ‘Chinese’ activity in Africa and the many faces of China’s ‘presence’ on the continent. That Beijing’s African policies are a threat to the promotion of good governance on the continent is a mantra frequently repeated in recent Sino-‐African scholarship (see: Breslin & Taylor, 2008; Dahle Huse & Muyakwa, 2008; Karumbidza, 2007; Naím, 2007; Power, 2008; Power & Mohan, 2008a). These critical writings accuse China of undermining efforts to improve transparency and accountability in Africa by financing and supporting authoritarian leaders and states, by supplying arms in conflict situations, by doing business without ‘ethical’ conditionalities, and by taking advantage of corruption. Many Western scholars argue that China’s behaviour threatens to undo the fragile gains that have been made in terms of democracy, transparency and accountability in Africa over the last six decades. For instance, in Zimbabwe, China is accused of funding the state’s ‘acquisition of military-‐strength radio jamming equipment to block opposition equipment ahead of the 2005 elections’ (Karumbidza, 2007). Accusations such as these have focused on Beijing’s apparent willingness to finance corrupt and autocratic regimes in Africa, and stories such as these are often denoted as being emblematic of Sino-‐African ties. Scholars are quick to point out China’s attractiveness as a lender ‘outside the existing hegemony of development actors and institutions referred to as ‘traditional’ donors or ‘the West/Western donors’ (Dahle Huse & Muyakwa, 2008, p. 8). They 25

- 26. warn that China appeals to African leaders through its discourses of ‘respect’ and ‘mutual benefit’, stressing that, unlike the West ‘China avoids the status of ‘donor’ and the word ‘aid’ is often avoided altogether when talking about Africa’ (Power, 2008). The post–9/11 security agenda has included a greater focus on ‘failed states’, counterterrorism activities and development. China now represents at least a geopolitical complication in Africa, at worst a threat in its relations with states and groups potentially hostile to the West (Mawdsley, 2007, p. 407). Amongst those who promulgate narratives which view China as a ‘hidden dragon’, there are many who view China as a ‘threat to healthy, sustainable development’ arguing that China is ‘effectively pricing responsible and well meaning organizations out of the market in the very places they are needed most’ whilst ‘underwriting a world that is more corrupt, chaotic and authoritarian’ (Naím, 2007, p. 95). There seems to be a real fear that China’s ‘rogue lending’ (Naím, 2007) will ‘burden poor countries with debt—a burden from which many have only just escaped’ (Lancaster, 2008, p. 1). Dahle Huse and Muyakwa argue that the lack of transparency in the disbursement process of Chinese ‘soft loans’ to African governments ‘makes it difficult to assess how much debt is being contracted and on what terms’ (Dahle Huse & Muyakwa, 2008, p. 5). They argue that ‘Zambian NGOs, donors and well-‐wishers need to keep a close eye on Chinese loans and raise the alarm when need be’ (Dahle Huse & Muyakwa, 2008, p. 5). 26

- 27. In summary; accounts, such as these, which frame discussions of China’s economic impact in Africa in terms of its role as an irresponsible financer of corrupt African regimes and general promoter of disorder in African economies, are characteristic of much recent writing on Sino-‐African relations. Indeed, in analysing writings published in English during the last two decades by African, European and American scholars on China’s engagement with Africa, we can identify the following popular tendencies: 1. A preference for generalised narratives of ‘China’ and ‘Africa,’ which flatten both sets of actors, producing a series of simplistic and dichotomous scenarios that ignore the complex interactions between different local actors and different Chinese actors, particularly members of the Chinese diaspora. 2. A preference for constructing ‘China’ as a powerful and homogenous force of chaos in Africa, suggesting that all aspects of Chinese activity in Africa are somehow related to the geopolitical ambitions of the Chinese state. 3. Implicit reference to supposedly ‘superior’ Western intentions and practices and a simplistic and half-‐hearted attempt at understanding African perspectives, motivations and interests with relation to China’s presence on the continent. While these tendencies are by no means universal in writing on Sino-‐African relations, they define the default parameters of imagined configurations of ‘China’ 27

- 28. and ‘Africa’ in which much academic writing on Sino-‐African relations is situated. For instance, accounts of Chinese activity in Africa have typically overlooked the hugely important role played by Africa’s diverse Chinese communities in changing consumptive habits in places such as Lesotho. While it is certainly true that the presence of the Chinese diaspora in Lesotho and other parts of Africa is an outcome of political and economic changes in China mediated by the Chinese state, my research shows that the vast majority of ‘Chinese activity’ in Africa is completely outside state control. Indeed, the majority of Chinese migration to Africa occurs through non-‐governmental channels and even in instances where migration was organised as part of official programmes of development assistance or resource extraction, individuals usually disassociate themselves from the Chinese state within a few years of arriving in Lesotho. In this way, Sino-‐African relations are increasingly dominated by individual interactions that transcend the nation-‐state. In conclusion, this paper seeks to fill a gap in the literature by providing a more balanced account of the multiplicity and complexity of engagements between ‘China’ and ‘Africa,’ avoiding the tendencies that Mawdsley argues are characteristic of so much writing on Sino-‐African relations. The intention is to provide a lens through which to understand the ways in which individual migrants deploy potential social networks to make a living in some of Africa’s poorest regions. 28

- 29. Chapter 3. Methodology 3.1 The Ethnographic Approach The essence of qualitative research is that it can construct and interpret a part of reality based on what grows out of the fieldwork – rather than on the researcher’s a priori theories and knowledge (Bu, 2006, p. 223). Bu’s assertion -‐ that good qualitative research is born out of an open-‐minded encounter with the field -‐ was highly influential in shaping my methodological approach to understanding Fujianese migration to Lesotho. The findings outlined in this paper are the product of an ethnographic study of resident Chinese in Lesotho, based on semi-‐structured interviews as well as informal conversations and participant observation. These informal meetings allowed me to corroborate conclusions drawn from my semi-‐structured interviews, a technique favoured by Kjellgren (2006, p. 237). Bu goes on to highlight the importance of going out into the field (Bu, 2006, p. 221). Although this may seem like an obvious point to make, it is worth stressing the centrality of ‘place’ in studies of migration and, hence, the fundamental importance of visiting the research site. Indeed, Pieke et al. argue that the aim of ethnographic research should be to seek to ‘elucidate the social processes that imagine, produce and challenge specific places and communities’ (Pieke et al. 2004, p. 6). 29

- 30. Speaking from experience, Pieke et al. point out that official figures and statistics on Fujianese migration are scarce and often unreliable. Consequently, they propose that ethnographic research is the most appropriate path for understanding the contingent and dynamic nature of Chinese migration (Pieke et al. 2004, p. 6). Furthermore, Bu stresses that insiders and outsiders may have different perceptions of the same event and that going out and speaking to people is the only way to gain a real insight into their worldview (Bu, 2006, p. 214). A good example of this is the extent to which definitions of ‘legal’ vs. ‘illegal’ are dependent on context, particularly in the case of Chinese migration. As Bu points out, maintaining a sensibility to the insider’s perspective can provide fascinating insights into the reasoning behind their actions and strategies (ibid., p. 223). 3.2 The Fieldwork For the purposes of this investigation, I travelled to Maseru, Lesotho’s capital and first port-‐of-‐call for foreign migrants. Unfortunately, limited time and resources meant that a wider survey of Lesotho’s resident Fujianese population would have been outside the scope of this investigation. Rather than spending days travelling between mountain villages in the hope of finding willing Fujianese respondents, I chose to focus my efforts on interviewing settled migrants in the Maseru district, which contains both Lesotho’s most populous urban centre and the country’s highest concentration of Chinese immigrants. 30

- 31. In total, I spent 17 days in Maseru, from the 3rd to the 20th of December 2010, conducting in-‐depth interviews with adult male and female urban residents of Mainland Chinese origin. Respondents were gathered through contacts in Lesotho, and later through ‘snowball sampling’ (Goodman, 1961). All interviews were conducted in Mandarin and lasted between 30 and 90 minutes. The total number of respondents was 25, ranging from shop-‐owners to hairdressers. The objective of these interviews was to answer the following questions: 1. What were the migrant’s aspirations in coming to Lesotho? 2. How do they perceive the ‘remoteness’ and ‘peripherality’ of Lesotho in relation to China and other ‘marginal’ Third World spaces? 3. In which sectors of the economy are they established and how did they become established in those sectors? 4. What are their present aspirations, do they intend to return to China? 3.3 Gaining Access As Heimer and Thøgersen point out, good contacts are often a necessary prerequisite for doing research, particularly when doing research on China and the Chinese (Thøgersen & Heimer, 2006). Having previously researched official Chinese development assistance to Lesotho, I understood the importance of ‘gatekeepers’ in providing access to research respondents. Fujianese migration to Lesotho was an entirely new research field for me and, as such, I had no Fujianese contacts on the ground to kick-‐start my investigation. Instead, I was compelled to take Solinger’s 31

- 32. advice and ‘draw upon any relationship one might have with any person willing to be of help in one’s ploy to meet potential subjects’ (Solinger, 2006, p. 157). Solinger also stresses the importance of retaining old contacts (ibid., p. 158). I was lucky enough to be able to remain in touch with one of the respondents from a previous visit to the field, a Taiwanese shop owner by the name of Mr. Lin. His practical assistance in helping to arrange meetings with Fujianese migrants gave me free access to respondents who would otherwise have been intensely suspicious of my project. Presumably out of the kindness of his heart, Mr. Lin devoted every afternoon of my time in the field to arranging interviews with recent Fujianese migrants, as well as with established resident Chinese from Shanghai and Taiwan. When I offered to reimburse him for his troubles, he refused, saying that he felt grateful that someone from a reputable academic institution had taken interest in the plight of Lesotho’s Chinese community. Mr. Lin would meet me every day at an appointed time before lunch with a list of respondents with whom he had arranged meetings. He would then drive in his pickup truck to see each of the respondents, negotiating access with security guards and escorting me onto their business premises. Not only was Mr. Lin’s assistance invaluable in terms of providing practical access and transport, but also in facilitating introductions and sometimes communication with Fujianese migrants to Lesotho. These individuals were understandably wary of a foreigner taking such a close interest in their presence in the country. Although the majority spoke intelligible Putonghua, there were occasions when I had to ask Mr. Lin to clarify the meaning of 32

- 33. Fujianese expressions or to translate from the Fujianese dialect into Mandarin. This, he did willingly, all the while allaying the suspicions of my respondents and helping to navigate through sensitive issues. Although I was grateful to Mr. Lin for sacrificing so much of his personal time and effort to assisting me in my research, I was also aware that his positionality as an economically successful Taiwanese resident in Maseru would have an effect on the findings of this investigation. As a result, I was careful to maintain a critical ear throughout my time in the field, subjecting Mr. Lin’s well-‐meant comments and theories to the same scrutiny as the information given to me directly by my respondents. However, despite Mr. Lin’s inexplicable dedication to helping me in my research, I have no reason to suspect him of having dubious ulterior motives and remain enormously grateful for all his help. 3.4 The Interviews Interviews were semi-‐structured, focusing on content rather than on the questions themselves. The approach was informant-‐focused, viewing the respondents as agents in an unfolding narrative, rather than ‘mere vessels of answers’ (Silverman, 1997, p. 149). The ‘pyramid strategy’ was used in all interviews. ‘Easy-‐to-‐answer questions’ were asked first and ‘abstract and general questions’ were asked last (Hay, 2000). The style of questioning was semi-‐formal, to allow for conversational development towards more ‘sensitive issues’ (ibid.). Notes were 33

- 34. taken during all the interviews and I typed up a daily report of my research findings for my own records. The difficulty involved in earning the trust of my respondents made me reluctant to rouse suspicions by seeking to record interviews electronically. Previous experience of interviews with Chinese in Lesotho had taught me that the mention of a Dictaphone could either end an interview or restrict the conversation to discussions of mundane topics. This echoes the advice given to Kjellgren by a Chinese-‐American scholar who blankly stated that ‘‘you definitely want to avoid carrying a tape-‐recorder if you want people to talk” (Kjellgren, 2006, p. 232). This seemed self-‐evident, given the ethical considerations involved in interviewing illegal migrants operating businesses without licenses. As a rule, I followed Solinger’s advice and only pushed sensitive topics as far as the respondent was willing to go (Solinger, 2006, p. 164). Given the emphasis placed by numerous authors on the proper acknowledgement of positionality in qualitative research (Pratt, 2000; Rose, 1997; Seale et al., 2007; Valentine, 1997), I was aware, going into the field, that my position as a student from Oxford with Mosotho ancestry could affect my investigation. Bu discusses the difficulties encountered by ‘outsiders’ in seeking to gain an insight into the lives of ‘insiders’ and the comparable difficulties faced by foreigners seeking to understand aspects of Chinese society (Bu, 2006). However, Kjellgren argues that these dichotomies are often unhelpful, since they allow little room for ambiguity in terms of race and background: 34

- 35. These twin dichotomies allow little room for most researchers of flesh and blood since few if any fit the racial and cultural stereotypes that come together with them, and needless to say they leave even less room for variation among the people on the other side of the notebook (Kjellgren, 2006, p. 225). Also, given the complex interplay of numerous prejudices between whites, locals and Chinese migrants in Lesotho, I was unsure of how I -‐ a mixed race researcher with a Sesotho name -‐ would be treated by my respondents. Rather than opt for dissimulation, I chose to be honest about my origins and my research agenda. Generally, I felt this was conducive to openness and, thanks to the mediatory role played by Mr. Lin, a considerable degree of trust was extended to me by my informants. Indeed, as I will explain, my ambiguous background often proved an advantage in navigating through the interview process. Solinger asserts that better knowledge of the context of the interview leads to better interviews (Solinger, 2006, p. 161). She argues that such prior knowledge can provide a ‘springboard’ for diving much deeper into more complex or sensitive issues (ibid.). For this reason I tried to read as much as possible about Fujianese migration to Africa before heading out into the field. Furthermore, having lived in Lesotho before and being partially of Basotho descent, I was able to display a degree of local understanding beyond that of a foreign researcher. However, even with the reassuring presence of Mr Lin at my side, many of my respondents were initially very suspicious and unwilling to discuss their private 35

- 36. histories of migration to Lesotho. When asked fairly mundane questions about the Chinese community in Maseru, several informants tried to deflect my attention onto the established Indian presence in Lesotho. This reluctance to communicate highlights the fact that the majority of Fujianese migration to Lesotho takes place through illegal channels and that those who stay in Lesotho often live outside the law. In most cases I was able to establish a workable degree of trust with my respondents but in some cases I was left to extrapolate information from their silences or their eagerness to discuss other topics. Rather than being disheartened by this lack of cooperation, I tried to remember Bu’s assertion that ‘even if we do not discover any absolute truths we can, at least, get somewhat closer to the realities’ (Bu, 2006, p. 223). My informants, like those questioned by Kjellgren, were keen to assess my level of understanding at an early stage in the interview. Like Kjellgren’s respondents, they wanted to know whether I knew enough Mandarin to be able to understand them, whether I knew enough about China to understand their references to home and Chinese culture, and whether I knew enough about Lesotho to understand the local situation (Kjellgren, 2006, p. 233). When seeking answers to more sensitive questions I was able to play up my ‘externality’ as an ‘outsider’ unlikely to report to the Lesotho government or to authorities at home in China. By contrast, my local understanding of the general situation of Chinese migration to Lesotho helped me to avoid generic discussions and focus on more personal accounts of transnational mobility. In this sense, taking 36

- 37. the time at the start of each interview to establish my positionality as an insider/outsider, rather than hindering the conversation, worked to my advantage, establishing a common framework for the discussion of both general and personal topics. In this way, I was required to present what Solinger terms a ‘Daoist-‐type’ ideal of understanding: appearing ‘at once knowledgeable but ignorant, knowing and not knowing’ (Solinger, 2006, p. 161). 37

- 38. Chapter 4. Findings and Discussion 4.1 Lesotho’s Established Chinese Communities The recent flow of Mainland Chinese migrants to Lesotho is by no means an isolated instance of transnational mobility. Indeed, it would be impossible to write a history of Mainland Chinese migration to Lesotho without referring to earlier flows of ‘pioneer migrants’ from Taiwan and Shanghai. In her study of Chinese communities in Zanzibar, Hsu identifies three distinct groups of Chinese on the island: government-‐sent teams, business people and an established community of overseas Chinese (Hsu, 2007). In Lesotho I have identified three comparable but distinct Chinese communities, each of which represents a different phase of Chinese migration, reflecting Lesotho’s position within global migratory flows at different periods in its history. First among these groups is the established community of skilled Taiwanese experts, originally sent to Lesotho during the early 70s as part of Taiwan’s official aid to Africa. Second is the community of skilled Shanghainese businesspeople, recruited by Taiwanese employers during the early 90s to run their businesses in the garment and retail sectors. Third is the larger community of recent arrivals from Fujian, consisting predominantly of unskilled traders who have established a virtual monopoly over the retail of basic consumer goods, penetrating into regions of Lesotho previously unreached by either foreign or domestic retailers. Taking 38