Chushingura Theatre

- 1. 7 S rs/, Id

- 2. The Double Identity of Chashingura: Theater and History in Nineteenth-Century Prints CHELSEA FOXWELL T HE HISTORY OF CHUSHINGURA in ukiyo-e begins with the actor and stage prints produced for the first kabuki performances of Kanadehon chushingura in Edo in 749.' Kanadehon means "Japanese syllabary (kana) copybook," chushingura the "treasury of loyal retainers"; the title implies that like a copybook, the deeds of the so-called loyal retainers should be emulated.2 Long known to the West as the story of the "forty- seven ronin," or masterless samurai, this play forms the core of a tradition of dramatic works based on an actual incident that began in the spring of 1701 inside the shogun's castle in Edo. Lord Asano Naganori, a provincial daimyo from the domain of Ak6 in modern Hy6go Prefecture on the In- land Sea, drew his short sword in a failed attack on KiraYoshinaka, a high- ranking Tokugawa government official. The motive behind the attack re- mains unclear despite numerous speculations; Kira went home to nurse his wounds, and Asano was sentenced to death by seppuku, which was carried out later the same day. Subsequently, forty-seven of Asano's retainers took it upon themselves to seek "revenge" against Kira, although there was no precedent for avenging the enemy of one's lord. On the fifteenth day of the twelfth month of Genroku 15 (January 30, 1703), twenty-two months following the death of their master, the retainers cornered Kira within his mansion at night, killed him and took his head, which they presented at Asano's grave at the temple of Sengakuji in Edo the next morning. The re- tainers then turned themselves in to the shogunal authorities and were sentenced to death by seppuku two months later. Collectively constituting one of the most shocking disturbances in the history of the city of Edo, these events are now known as the Ak6 incident of 1 701 3 .3 As early as 1703 allusions to the incident were made on stage, and entire plays based on the Ako incident emerged following the death of the shogun Tsunayoshi in 1709. First performed as a puppet play (joruri) in Osaka in the fall of 1748, Kanadehon chushingura, written byTakeda Izumo 11 (1691 I756), Miyoshi Sh6raku (1692 1772) and Namiki Senryu (i 695-I7g 1), surpassed these early works with a grand, eleven-act portrayal that con- cludes with the night attack of the loyal retainers. 4 Within weeks produc- ers brought Kanadehon chushingura to the kabuki stage, where it is per- formed to this day. As this vivid dramatization secured its place in the rep- ertoire of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the "Chushingura" of its < Fig. 4. Katsushika Hokusai. Kanadehon title came to be used in an all-encompassing manner to indicate both the chushingura, act [ i. i8o6. (Detail) Ako incident and the range of cultural production that arose in its wake. IMPRESS ION S 26

- 3. The historian Henry D. Smith II has recently analyzed this vast "Chushingura phenomenon," which both shaped and reflected people's conception of the incident in the latter half of the Tokugawa period. One of the key features of the Chushingura phenomenon is its dual iden- tity as a stage tradition and as the commemoration of an actual event. Even before the writing of Kanadehon chushingura, traveling preachers (koshakushi) played a vital role in spreading awareness of the Ako incident through their oral accounts of it. These narratives (kodan) drew on rumor and imagination as well as on written records whose identity was ob- scured in the complex process of retelling. Kodan narratives proliferated from the late eighteenth into the nineteenth century, spawning and in turn absorbing details from historical (jitsuroku) novels about the ronin. Originally these historical novels circulated in manuscript form through lending libraries, but shogunal proscriptions against presenting the Ako incident in print were gradually relaxed in the nineteenth century, giving rise to a flourishing output of publications on the subject during the 18 ýos. Meanwhile, Sengakuji grew in importance as a site to commemorate the loyal retainers. In the field of ukiyo-e, CONCORDANCE landscape and warrior prints emerged as new genres, supplying a broader range of opportunities for presenting Sengakuji and the forty- Historical figure Chushingurarole seven ronin. As a result, nineteenth-century prints moved beyond the KiraYoshinaka Ko no Moronao stage, basing their conceptions on the theater but including refer- ences to the historical incident, especially to its setting in Edo. The Asano Naganori Enya Hangan print medium proved particularly capable of unifying the two realms Oishi Kuranosuke Oboshi Yuranosuke by means of a single visualization that allowed for a double reading as history and as stage performance. Curiously, the duality of the Chushingura phenomenon is paralleled in the theater by the workings of a conceptual device known as the "world" (sekai). The sekai drew upon the audience's knowledge of older medieval tales and story cycles. The incorporation of a new dramatic narrative within a familiar world was a source of pleasure and stimulation. At the same time, however, and particularly in the case of the Ako incident, the sekai functioned as a way to talk about "forbidden topics.", In the case of Kanadehon chushingura and related plays, the characters and plot of the popular fourteenth- century warrior chronicle Taiheiki (Chronicle of great peace) form the world through which the Chushingura narrative is pre- sented. In the theater and in prints Lord Asano appears as Enya Hangan (d. 1341), a country warrior from the remote province of Izumo. Kira, the object of Asano's enraged assault, is transformed into the Ashikaga shogunal official Ko no Moronao (d. 13B ). In the Taiheiki, Moronao heaps I slander on Enya after an unsuccessful attempt to seduce Enya's wife and eventually causes the couple's deaths. Before disemboweling himself, Enya swears, "I will be reborn seven times as Moronao's enemy."' Blend- ing this Taiheiki world with details of the recent Ako incident, Edo-period playwrights encouraged a creative doubling that fueled later treatments of the theme. For example, Kanadehon ch6shingura applied the personality of Moronao in the Taiheiki to the historical Kira; while Asano's motives in attacking Kira remain unknown to this day, the Taiheiki world intro- 24 FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

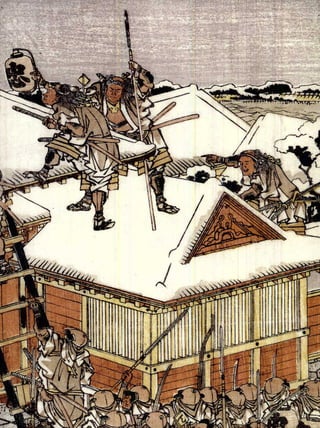

- 4. Fig. i. Artist unknown. Perspcctive Print of duced the possibility of lechery as a motive, vilifying Kira along the lines Kanadchon chushingura at the Twio of Moronao. icaters (Kanadehon chushingura ryashibai Nineteenth-century prints might be said to mirror contemporary viewers' kyogen iki-e). 1749. Color woodcut, urushi-e. 2,. 2 x 4 3 cm. Waseda Univer- understanding of Chuishingura, which was informed and embellished by sityTheater Museum Collection, Tokyo the workings of the sekai and by an expanding variety of sources. Many ( l oo-o868) nineteenth-century images made simultaneous reference to the stage and In tih climactic night attack of act i i the to elements of the historical incident as they were known through elabo- loyal retainers break into Moronao's rate oral retellings. For example, the background details in landscape or "scenic" renditions evoke the historical setting of the Ako incident. Por- mansion. They find him hiding among rice bales at the left. traits of the ronin draw upon highly imaginative tales of the individual re- tainers (gishi meimeiden) to enrich and extend the "main tale" (honden) of the night attack. Depictions of episodes following the attack bring Sengakuji, the gravesite of the actual retainers, into sharp focus. Without necessarily letting go of the world of the Taiheiki or the conventions of the kabuki stage, many nineteenth-century Chfishingura prints bring us visu- ally closer to Edo and thus to the historical Ako incident. The prints cir- cumvent Tokugawa government taboos by merging stage and historical elements through visual means. They also reflect interest in the real-life setting and details of the Ako incident, details which are suppressed or concealed in the play. THE SCENIC CHOISHINGURA Scenic Ch-ushingura prints represent the physical setting of the narrative through techniques of spatial rendering, atmospheric effects and detailed polychrome printing. An important early uki-e ("perspective picture") ex- ample has been dated to 1749 by the Waseda University Theater Museum IMP R ES SIGNS 26

- 5. Figs. 2a, b. Katsukawa Shunko. Acts 5 and 6, from the series Kanadehon chushingura (Kanadehon chushingura, godanme, rokudanme). c. 1 774.Two color woodcuts, hosoban. 2a: 31.7 x 14.3 cm; 2b: 3 1.5 x 14 cm. Waseda University Theater Museum Collection, Tokyo (0oo-0990, O99I) In act g (fig. 2a), the masterless samurai Kanpei, a former retainer of Enya Hangan, prepares to shoot a wild boar (on the path behind him), while the bandit Ono Sadakuro clings to a tree in alarm. In act 6 (fig. 2b), Okaru, Kanpei's wife, who has been sold into prostitution by her parents in order to raise money for Kanpei to join the league of loyal ronin, prepares to leave in a palanquin. Returned from the hunt (his gun rests against the wall), the troubled Kanpei be- lieves he has shot his father-in-law by mistake. on the basis of the distinctive use of the term "the two theaters" (ryoshibai) in the title (fig. i). This is a reference to two near- simultaneous competi- tive runs of Kanadehon chushingura at the Ichimura and Nakamura theaters in Edo during the fifth and sixth months of Kan'en 2 (i 749). The repre- sentation of two different performances in a single image is probably un- precedented. And unlike the more familiar category of perspective print showing actor and audience surrounded by the faithfully rendered equip- ment of the stage, this image of the two plays includes neither audience nor theater architecture. Instead, it is striking for the way in which it sets the play in real life, within a naturalistic setting. Traces of the theater re- main, as in the matching uniforms with a chevron pattern, which were taken straight from the stage. In addition, the kana tag attached to each man (the individual kana syllables of i,ro,ha functioning as identifiers) is a reference to the "kana copybook" (kanadehon) of the play's title. So the "double identity" of Chushingura is already clearly visible in this very early depiction, part real life and part stage. The scenic print further developed with the emergence of act-by-act Chfi- shingura stage prints produced as a series. This practice began in the 1770s with Katsukawa Shunsho (1726 1792) and his pupils, who were known for their likenesses of individual actors. Katsukawa Shunko (1 743 181 2), for example, fabricates an imaginary Kanadehon Chushinguraper- formance that stars leading actors in each of the main roles (figs. 2a, 2b).9 These actor prints resemble narrative painting in their high vantage points FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 6. Fig. 3. Katsushika Hokusai. Kanadehon chushingura, act g. i 806. Color woodcut. 2 ý.9 x 37.9 cin. Honolulu Academy of Arts, Gift of James A. Michener, iggi (2 ý ,72 8) In the foreground the bandit Ono Sadakuro killsYoichibei, Kanpei's father-in-law, during a rainstorm and steals the money intended to help Kanpei join the league. Beyond, the scene of Kanpei and the boar hunt is represented. Fig. 4. Katsushika Hokusai. Kanadehon chushingura, act i i. 1806. Color wood- cut. 25.6 x 37.9 cm. Honolulu Academy of Arts, Gilt of James A. Michener, 1991 (21,899) The loyal retainers break into Moronao's mansion before dlawn. and background detail. The scenic approach also provides the space and organizing logic to portray consecutive narration over a span of time, as with Kanpei and the fleeing boar in act g, or with Okaru in act 6, ready to depart for the brothel in a palanquin and unaware of Kanpei's anguish as he sits inside the house. In i8o6 Katsushika Hokusai (I 760 184-9) created an act-by-act Kanadehon chushingura series that was unmatched in the sensitivity and rich detail of its landscape settings (figs. 3, 4.)"° Use of deep perspective views in this series represents the culmination of previous attempts to evoke a natural- istic setting for Chushingura performances. Background scenery helps to express the mood of each act. Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1 861) followed Hokusai's lead with Chashingura, ii: The Night Attack (fig. 5), an uncon- Act ventional landscape study in perspective and shading. Here some of the IMPRESSIONS 2)

- 7. Fig. ý. Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Chushingura, retainers orchestrate the silent, cautious break-in to carry out their late Act ii :The Night Attack (Chushingura master's unfinished business. Wearing matching black and white robes and juichi-donmeyouchi no zn), from an bearing weapons and other equipment, they are about to conclude untitled series of views of the city of months of waiting and preparation for the attack. The open moonlit Edo. c. 1830 3 . Color woodcut. space, tiny figures and strong receding lines establish a mood of eerie 26 x 37.5 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, calm and anticipation. The foreground is given over to the neighborhood Springfield, Mass., Raymond A. Bidwell dogs, which are silenced with handouts from one of the samurai. Collection Although titled Chushingura,Act ii, this urban landscape corresponds more closely to contemporary Edo than to the world of the theater. The expan- siveness of real space is suggested by means of a restricted color palette, low horizon line, Western style recessive diagonals and shadows. The print also offers a convincing sense of temporality: the light of the full moon on the snow evokes the eve of the fifteenth day of the twelfth month, the date of the actual attack on Kira's mansion. Kuniyoshi shares the perspective approach of Hokusai, but the single- sheet Night Attack creates an even greater sense of remove from the fea- tures of kabuki performance. The image is clearly not an actor print, and while the title refers to "act ii ," the name of the play is generalized as Chushinguraand does not seem to refer to a specific production. Com- pared to the Hokusai figures, who have more detailed facial expressions and pose like actors, the faces of Kuniyoshi's men are restrained and anonymous. This difference alerts us to Kuniyoshi's main innovation: while actor prints invariably celebrate the dynamism and charisma of in- FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 8. dividuals, Night Attack deemphasizes the protagonists, going so far as to prevent them from occupying the central area of the composition. Insis- tence on the features or gestures of a particular figure would have de- tracted from both the singularly captivating mood and the starkness of the composition, with its heavy shadows. Furthermore, by avoiding the flam- boyant actor figure, Kuniyoshi constructs an ambiguous setting, encourag- ing a double reading as act i i of "Chushingura" performed on stage and as the 1703 attack on Kira's mansion in Edo. Double readings had already been encouraged by earlier scenic Chushin- gura prints, which combined kabuki conventions with detailed indoor and outdoor scenery. Over time, however, Chushingura prints reached greater levels of detachment from the theater through elaboration of the setting. As a natural result of this, Night Attack and other Chushingura prints of the same period invoked the historical incident as it was known to many view- ers through oral retellings and historical novels. However, like the plays, the prints stopped short of direct reference to the "forbidden topic" of the Ako incident. The explicitness of the setting in Kuniyoshi's print is there- fore remarkable. With his scenic rendition, the artist takes us away from the stage and back toward the forbidden site of Edo. THE NIGHT ATTACK AND THE RETREAT TO SENGAKUJI: CONFIRMING THE SETTING IN EDO The 184os and i8;os saw a sudden surge in the popularity of the Ako inci- dent and Chfushingura theme. Several Chashingura prints and print series were published in or around the year 1848, which marked the hundredth anniversary of Kanadehon chushingura.A new generation of printed ac- counts of the Ako incident appeared beginning in the early 18 8os, in par- ticularYamazakiYoshishige's Ako gishiden issekiwa (A night tale of the righ- teous men of Ako) of 18 4, which was not banned despite its use of Ako in the title." In 1864, Utagawa Kunisada ( 1786-1864) published the actual names of the retainers alongside the names and portraits of contemporary actors in his print series Lives of the Loyal Retainers (Seichu gishiden). This was evidently intended to enhance the commercial viability of the series. The last decades of the Edo period were not only a time of great popularity for Chfishingura, but also a period when its double identity as history and the- ater was explicit. Kuniyoshi designed at least ten series and over a dozen triptychs on the Chushingura theme during the 184os and i85os. " In the triptychs particu- larly, a different category of Chushingura print rose to prominence. Rather than beginning with the prologue and ending with the night attack and finale of act i i, this category encompassed a new cycle of compositions that started with the night attack and moved on to the procession to Sengakuji (thinly disguised as Sengokuji) and to subsequent events: the sake toast at dawn, the burning of incense before the tomb and the wash- ing and presentation of the head of Moronao (or Kira). " These events ap- pear in the earliest accounts of the Ako incident, including those of the retainers themselves.'4 While similar events may have been performed on stage prior to the end IMP RE S I ON S 2(

- 9. Fig. 6. Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Having Achieved Their Goal, The Loyal Retainers Retreat to Sengokuji (Gishi honmo o tasshite Sengokuji ni hikitori-katameno zu). c. 1847-5 2. Color woodcut, triptych. 36 X 24 cm each approx. David R. Weinberg Collection The chief retainer, Oishi Kuranosuke (Oboshi Yuranosuke), is seated in the central panel. The setting appears to be a large two- story temple gate, but the actual main gate (chumon) of Sengakuji was quite modest; it appears in fig. 7 just beyond the long flight of steps on the left-hand page. Another example of artistic license is the inclusion of the bay, which in reality is not visible from the temple. 30 FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 10. of the Edo period, they were not a part of Kanadehon ch5- shingura, which concludes with the night attack. In act i i of Kanadehon chushingura, after taking Moronao's head the re- tainers learn of their imminent pursuit by the forces of Moroyasu, Moronao's younger brother. Chief retainer OboshiYuranosuke declares, "Yes, it would be best to end our lives before our master's tomb. We will withdraw."' I The play closes with lines of praise for the retainers. Given the potential for drama in envisioning the "retreat to Sengakuji," why would Kanadehon chashinguraend so abruptly at the man- sion of Moronao? The answer involves the controversy surrounding the actual night attack and assassination of Kira. After a long period of deliberation the Tokugawa govern- ment made its final judgment of the action taken by the re- tainers. In the second month of Genroku 16 (March 1703), the government issued a sentence of death by seppuku for the forty-six retainers who had turned themselves in. 6 While the play celebrates the men as models of loyalty, some members of the Tokugawa government seem to have been divided in their opinions. The Confucian scholar Ogyu Sorai 1(I666- 1728), for example, who was in the service of a shogunal adviser, articulated the position that engaging in mass violence for the sake of one who had been punished by the government was legally unacceptable.'7 The historian Bito Masahide adds that the Ako retainers were consciously "undertaking an action ... which objectively constituted a protest against state authority."'" Because it appeared to challenge the justice of the shogunate's initial decision to execute Asano but not Kira, the conduct of the Ako retain- ers could be interpreted as politically subversive and was best not dwelt upon in the theater, even obliquely.'9 By hav- < Fig. 7. Hasegawa Settan (1778-1843). ing the retainers take their own lives at the temple, the play avoids direct Scngakuji, from Illustrated Guide to Famous reference to the shogunate and its subsequent execution of the ronin. Places oýf do (Edo tucisho zue), vol. 3. Nineteenth-century ukiyo-e printmakers portray the aftermath of the 1834. Woodblock-printed book. 26 x night attack, but they do not proceed past the memorial site of Sengakuji. 19. 1 cm approx. each page. Spencer The retainers are unambiguously extolled as loyal and righteous. Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, andTilden The Soto Zen temple Sengakuji served as the mortuary temple of the Foundations (Sor. 8 1) Asano and several other daimyo families. While the details of its history as a pilgrimage site in Edo are largely unknown, it attracted visitors from the time of the retainers' "retreat" to present the head of Kira before the grave of their lord. Following the deaths of the ronin, the temple became a repository of objects and documents associated with them. Sengakuji made an effort to attract visitors through exhibitions of its treasures at home and at other temples outside Edo. 20 In the triptych Having Achieved Their Goal, The Loyal Retainers Retreat to Sengokuji of about 1847-5 2, Kuniyoshi shows the retainers as they as- semble outside the imposing temple gate, with the chief retainer, Oishi Kuranosuke-labeled with his Kanadehon chushingura name of Oboshi IMPRESSIONS 26

- 11. Fig. 8. Hashimoto Sadahide. View of the Yuranosuke seated in the central panel (fig. 6). The retainers climb to- Loyal Retainers Gatheringto Celebrate at a ward Oishi from the lower left, where snowy cliffs drop away sharply to Sake Shop While Retreating After Achieving reveal the sensitively inked view of Edo Bay at dawn. Their Goal (Gishi honmo o toge sakaya ni atsunari iwatte hikitori no zu). 183Os. Retreat to Sengokuji is geographically specific and brings viewers closer to Color woodcut, triptych. Each sheet the memory of the Ako incident. The actual temple was located just north approx. 34.3 X 23.2 cm. Collection of of Shinagawa in the area known as Takanawa. The view of the bay in Henry D. Smith II Kuniyoshi's triptych evokes the dramatic setting in Takanawa and suggests the route along which the retainers made their way. A contemporary over- The retainers are said to have stopped for a view of the expansive Sengakuji complex appears in the multivolume gaz- toast on their way to Sengakuji. etteer Illustrated Guide to Famous Places of Edo (Edo meisho zue), published in 1834--36 (fig. 7). The building shown in the triptych may be the main hall at the back of the compound (upper right in fig. 7), although its architecture suggests a two-storied gate. There are mortuary tablets visible beyond the red pillars. Takanawa appears prominently in color woodblock prints of the city of Edo and of the stations of the Tokaido. 2" Views of Takanawa typically show descending geese and an autumn moon, which may allude to the poetic EightViews of Xiao and Xiang or of Omi.22 Curiously, Chushin- gura prints of the retreat to Sengakuji often incorporate the same lyrical FOXWELL THE DOLIBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 12. details even though the event occurred in the twelfth month, not in autumn. At the same time that Chu- shingura prints of the 184os and 185os reached a fresh visual specificity not rooted in the dramatic tradition, they also retained many of the verbal conventions linking them to the stage, most prominently the fic- tional names of the retainers and their leader, Oboshi. The prints also reflect verbal conventions that devel- oped offstage, such as the substitution of the real temple name Sengakuji with an aural approximation, "Sengokuji." Sengokuji, which did not exist except as a play on the word Sengakuji, was much more explicit than the Kanadehon ch6shingura script's use of Komyoji, an actual Kamakura temple from the Taiheiki world. In many nineteenth-century prints, the phrases "loyal retainers" (gishi) and "true aim" (honmo) convey the subject matter without using the words "Chushingura" or "Ako." This care in wording reflects the realities of government censorship, but more impor- tant, it participates in a consensus on language for dis- cussing the Ako incident, which retained its currency well after censorship ceased to be a concern. In these ways, Chushingura prints both elaborate on Kanadehon chushingura and incorporate elements of the historical incident as it was recalled at Sengakuji. The prints extend the narrative, creating a visual rep- ertory that stretches beyond the finale of the play. At the same time, they revise the setting, using imagery that was continuous with the time and space of the print audience, who could personally visit Sengakuji to confirm the names and deeds of the retainers while burning incense at their graves. PRINTS OF THE INDIVIDUAL RETAINERS Hokusai's i8o6 Kanadehon chushingura, act i i (fig. 4) and Kuniyoshi's Night Attack of about 1830 35 (fig. 5) show the retainers as a group united in their aim and make few distinctions between them. By contrast, Kuni- yoshi's triptych Retreat to Sengokuji of about 1847 g2 (fig. 6) and similar contemporary images provide the next level of detail, identifying the re- tainers by name in small cartouches within the print. The names given, however, are not those of the original ronin but rather the slightly altered appellations by which the men became known through oral and written biographies (gishi meimeiden). Early accounts of the Ako incident, later historical novels and traveling storytellers enhanced the aura of accuracy of their presentations by listing the full names, ages (in 1703) and bureaucratic positions of each retainer, although in reality this information was subject to inconsistencies. Kuniyoshi's Retreat to Sengokuji and the triptych View of the Loyal Retainers IMP RES S I ON S 2 6

- 13. Fig. 9. UtagawaToyokuni I. Kanadehon Gathering to Celebrate at a Sake Shop While Retreating After Achieving Their Goal chushingura, act i i. 1816. Color wood- by Hashimoto Sadahide (I 8o 7-1873) (fig. 8) attempt to account for each cut, triptych. 36.4 X 24.3 cm each retainer. The latter print provides each name in a small cartouche, while approx. Waseda University Theater the faces show a realistic range in age and temperament. These triptychs Museum Collection, Tokyo (io o0-88o, reflect an overall attempt to individualize the retainers.2 3 The formal basis o881, 0882) for picturing the retainers, meanwhile, developed in accord with the mod- Ichikawa Danjuor6VII as Oboshi Yuranosuke els employed by a range of nineteenth-century actor and warrior prints in (right), Matsumoto Koshiro V as Ko no which the distinctive Utagawa-school figure style predominated. Moronao (center) and Bando Mitsugoro III as Fuwa Kazuemon (left) in a performance A late triptych by Utagawa Toyokuni I (s 769 182 ) exemplifies this trend at the Nakamura Theater in the seventh (fig. 9). It shows a performance of Kanadehon chushingurathat opened on month of Bunka 13 (1816). the seventeenth day of the seventh month of Bunka 13 (s 8 I6) at the Nakamura Theater in Edo. Ichikawa Danjuro VII (0 79 1-1 859) appears as OboshiYuranosuke at right and Bando Mitsugorb III (1 775- 832) as the ronin Fuwa Kazuemon at left, in the moment of their discovery, just be- fore dawn, of the cowardly Ko no Moronao (played by Matsumoto Koshiro V, 1768 1838) among the rice bales (for an earlier version of this scene, see fig. i ). The actors wear stage makeup and heavy brocades along with their characteristic black and white robes. The darkened sky and the snow situate them in a naturalistic landscape setting that goes beyond a stage set, and their poses convey the stage convention of the "frozen moment."'4 The relationship of the Toyokuni triptych to the equally dynamic and var- ied serial depictions of the retainers becomes clear when the left and right parts of the triptych are viewed in isolation. Danjuro as Oboshi, shoulders squared, raises the "lantern of loyalty," while the more muscular Bando Mitsugoro as Kazuemon, depicted at an angle suggestive of fore- shortening, thrusts his lance toward Moronao. Viewed on its own, each 34 FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 14. Fig. io. Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Teraoka sheet of the triptych resembles one of the serial depictions of the indi- Heienion Nobuyuki, from the series Lives vidual retainers. of the Loal Retainers (Scichu gishi den). c. 1847 48. Color woodcut. 3&.6 x Actor prints and warrior prints both feature a dynamic, individualized fig- 24.7 cm. David R. Weinberg Collection ure or small group of figures caught in mid-action and often placed against a stark background. Warrior prints, however, draw on narrative traditions Fig. ii. Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Sugenoya outside of the kabuki stage, often presenting one climactic moment for .Sannojo Masatoshi, from the series Lives visualization and supplying the rest of the narrative in an accompanying ofthe Loyal Retainers (Seichu gishi den). text passage. Serial compositions of the individual retainers readily c, 1847 48. Color woodcut. 37 X 2 straddle the actor and warrior print genres; popular enthusiasm for star cm. David R. Weinberg Collection actors presumably backed this trend. The immense success of Kuniyoshi's Lives of the Loyal Retainers of about 1847 48 (figs. io, i i) and the 1864 se- ries of the same title by Utagawa Kunisada (fig. 12) can thus be viewed in light of kabuki patronage. In series such as Lives of the Loyal Retainers, the costumes and faces of the individuals are often drawn in a way that suggests they are actors moving on a stage. The pretense to truth in portraying the retainers and their sto- ries becomes a pretense to truth dramatized, so that we imagine a play based on the real-life tales of the individual retainers, much in the way that Kanadehon chashingura is a dramatization of the real-life Ako incident. Kuniyoshi's Lives of the Loyal Retainers met with great success, attributable to the variety of poses and attitudes assumed by the retainers and to the alter- nating humor and drama of each print.2 The youthful, earnest expression of Teraoka Heiemon Nobuyuki (fig. i o), who is absorbed in the act of ex- tinguishing the coals in a brazier (a reference to the pains taken to avoid fire hazards and disturbances during the night attack), contrasts with the image of Sugenoya Sannoj6 Masatoshi (fig. i ) entangled in the streamers of a IMPRESSIONS 26

- 15. scent ball (kusudama). His "true aim" now slightly confounded, Sugenoya struggles to regain his balance. The comic and affecting qualities of the series seem designed to appeal to a theater-going audience. Okano Kinemon Kanahide (fig. 1 2) in Kunisada's 1864 Lives of the Loyal Retainers handles the kusudama with more aplomb. This orna- mental ball a sign of festivity or a charm against evil-is not asso- ciated consistently with one character but may refer to a narrative detail added to embellish retellings of the night attack: perhaps one of the ladies of Kira's household threw such a ball in an attempt to ward off an attacking ronin. All the subjects in this series are de- picted in the close-up format, with a brief biography of the ronin in question at the top of each print.2" The name of an actor appears alongside each figure. For example, the print of Okano presents the actor Ichikawa Shinsha I ( 182 1-18 7 8), even though the image has no known link to any specific performance of the type normally 21 commemorated in actor prints." Kunisada similarly used the names and faces of actors in the Collection of Famous Restaurants of the Eastern Capital of 18 2, a series he designed together with Utagawa Hiroshige (7 797- 1858). " On the whole, series such as the Lives of the Loyal Retainers constitute a distinctive type of Chushingura print. In style and conception the Fig. 12. Utagawa Kunisada. Okano prints reveal deep affinities to the actor prints that were the original mani- Kinemnon Kanahide, from the series Lives festation of Chushingura in ukiyo-e, encouraging audiences to imagine the of the Loyal Retainers (Seichu gishi den). most popular actors of the day in the roles of the retainers. The text pas- 1864. Color woodcut. 3;.7 X 24.3 cm. sages provide viewers with information on the lives of the retainers that Waseda University Theater Museum may have been gleaned from oral retellings and other written sources. By Collection, Tokyo (oo6 -5171) including diverse information about the Ako incident while simultaneously preserving links to the stage, Kunisada and his contemporaries created some of the most celebratory images of Edo-period samurai in existence. MEIJI CHCiISHINGURA: BACK TO THE STAGE In November 1868, less than one year after the capitulation of the Tokugawa shogun to forces proclaiming the restoration of direct imperial rule, thus inaugurating the Meiji period (18688-i91 2), Emperor Meiji is- sued a letter of commendation to the men of Ako. During a time when it was still battling opposition, the new government clearly stood to benefit from the long-standing popularity of a narrative that emphasized loyalty to one's lord, a feeling that might now be directed toward the emperor him- self. When he entered Tokyo in the fall of 18 68, the government made as- siduous efforts to win the hearts and minds of the people through patron- age of the most popular places of commoner pride and devotion, including Sengakuji. "'By the late Edo period, numerous exhibitions of ronin ephem- era accompanied the affirmation of Sengakuji as an important urban site for commemorating the Ako incident and its principal agents. After impe- rial envoys conveyed the letter to the retainers' graves at Sengakuji, the spirits of the "loyal league" were enshrined in a new memorial hall near the temple grounds. There, the forty-seven wooden statues commissioned in the i84os by a group of private individuals were put on display."3 FOXWELL THE DOUBLI IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 16. During the slow collapse of Tokugawa power and the construction of the Meiji state, kabuki was freed from general restrictions on the representa- tion of current events and of the Ako incident, which had occurred more than one hundred and fifty years earlier. Theater prints of the 186os and 187 os indicate that performances now appropriated the full range of Chu- shingura traditions, reformulating them for the stage. The prints docu- ment the production of witty Chuishingura pieces, including new composi- tions by the celebrated playwright Kawatake Mokuami ( 18 16 1893). Per- formed at the most important theaters of the capital, these plays drew on the main tale or on stories of the individual retainers. The corresponding images bear little relation to the Edo-period landscape print. They can- didly acknowledge the architecture of the stage, showing the actors against brightly patterned sliding doors or a stage curtain. 3 Even in the Edo period large theaters often faced financial difficulties and other impediments. In 1873, when the Meiji government suddenly in- creased the number of licensed theaters inTokyo from three to ten, there was stiff competition to attract an audience. The legalization of previously unlicensed small theaters (koya) in the area of Ryogoku Bridge added to the financial troubles of the three main theaters, which were already struggling to recoup their losses from the tumult of the 186os. While some efforts at turning a profit involved drastic innovation, most relied on the draw of the classics, which could be enlivened with a few novel touches or with variations on a theme. Prints for a November 1878 run of Kanadehon chushingura at the Shintomi Theater in Tokyo represent the theater at the height of its success in a new location. IIThe eleventh month marked the start of the kabuki season, when the entire company was introduced (kao-mise, literally "showing the face") in anticipation of the performances that would run through the ninth month of the following year. The placement of Kanadehon chclshin- gura in the November lineup suggests that an all-star performance of the classic play was conceived as a strategy for augmenting the popularity of the theater. Furthermore, the 18 7 8 Shintomi performance rotated differ- ent actors for the major roles on different days. While kabuki had a long tradition of starring one actor in multiple roles, this extraordinary variant on the tradition demanded that multiple actors be prepared to play at least two big roles. One of the images associated with this accomplishment was a so-called trick picture (shikake-e), or "picture with offspring" (komochi-e), by Toyohara Chikayoshi (active 18 7os- 18 8 os) depicting Enya Hangan's seppuku in act 4 of Kanadehon chushingura (fig. I3). Hangan (representing the historical Lord Asano) plunges the dagger into his abdomen at right, while Oboshi (representing chief retainer Oishi Kuranosuke, whose house crest is the double comma [futatsudomoe]) has arrived just in time to bid his master farewell. Different actors played the roles of Hangan and Oboshi on different dates: a large cartouche lists a sequence of five names for each part (most actors took both roles and their names appear twice). A stack of four small sheets of paper, each imprinted with a different head, is af- fixed to the first pair of heads shown in the diptych. The viewer can flip through the successive heads, referring to the cartouche above to deter- mine the names of the actors. The diptych is shown here with several IMPRESSIONS 2o

- 17. Fig. 13. Toyohara Chikayoshi. Kanadehon Chushingura, act 4. 1878. Color woodcut, komochi-e ("picture with offspring") diptych. 36. 2 X 2 4.3 cm each. Waseda University Theater Museum Collection, Tokyo (000-0321, 0322) The heads shown in this trick picture are those of Ichikawa Sadanji I as Enya Hangan committing seppuku and Onoe Kikugoro V as Hangan's chief retainer, Oboshi Yuranosuke. sheets of each stack raised to show the head below: Ichikawa Sadanji I (1842 1904) as Hangan, Onoe Kikugoro V (1844-1903) as Oboshi.34 A triptych entitled Competingfor the Role of 6boshi by Morikawa Chikashige (active second half of the i 9 th century) accompanied the same 1878 per- formance at the Shintomi Theater. The five actors listed for the role of Oboshi in the trick-picture diptych also appear here in the role of Oboshi (fig. 14). From right to left they are Sadanji, Ichikawa Danjuro IX ( 838- 1903), Nakamura Sojuiro (i 83 -1889), Kikugoro and Nakamura Nakazo III (i 8o9 i886).The image tantalizes fans with the notion that the actors deliberately competed with each other to give the best performance of the role. A tug-of-war involving a loop of rope around the necks of the competitors serves as a visual metaphor. Though Meiji prints differ stylistically from the scenic Chushingura print, it was in the Meiji period that the goal of linking the Chushingura drama to its historical setting came closer to onstage realization. The project of enriching kabuki with a greater degree of historical accuracy became a pillar of the state-supported kabuki reform of the 187os through the i 89os.11 Kawatake Mokuami and Ichikawa Danjfiro IX strove to infuse kabuki characterization and staging with "realism"; historians coached Danjuir6 on a monthly basis in an effort to increase the historical fidelity of the productions. 1" In preparation for his performance of the scene of Enya's seppuku in act 4 of Kanadehon chbshingura, for example, Danjuro IX was said to have carefully investigated the custom of closing the open hand of a dead person, as Oboshi does after taking the dagger from Enya's hand. Such efforts were predicated on the idea that from the Meiji period on, kabuki should incorporate new techniques, and it was open to all the top- ics that had been forbidden under the Tokugawa government. The ideo- logical reassessment of Chushingura in the Meiji period highlights the role 38 FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 18. Fig. x1. Morikawa Chikashige. Competing of late Edo-period prints as visual devices that had covertly and ambigu- ,for the Role oY'Oboshi (Futatsudomoe ously linked the performance of Kanadehon chushingurato the urban set- kyoso). 1878. Color woodcut, triptych. ting of the real Ako incident as it could never have been done on stage. 3 .4 x 23.6 cm each approx. Waseda University Theater Museum Collection, "Tokyo (I oo-I 12, 1I13, 1514) Visually and thematically, Chiushingura prints confirm the night attack as the most potent emblem of Chushingura and the Ako incident. The attack is suited to this role not only because it presents a climactic moment in the narrative that reflects the dancelike drama of kabuki, but also because it simultaneously evokes the peripheral tales of each retainer and antici- pates the "triumphant" procession to follow. The historian Miyazawa Seiichi notes that perhaps the most provocative Meiji-period Chfishingura play was inspired by a contemporary event known as the Incident at Sakurada Gate. Taking Revenge in the Snow:A Record ofAk5 (Kataki-uchiyuki noAkoki) opened at the Sawamura Theater in the Ky6bashi area of Tokyo in 1874. It presented the 186o assassination of the daimyo Ii Naosuke ( 18 15- 186o), a vassal of the shogun, through the lens of the time-honored Chushingura theme, just as the Ako incident was once presented through the Taiheiki. I Casting the daimyo in the role of Kira and presenting his assassins as the loyal ronin, this play capitalized on the fact that like the night attack on Kira's mansion, the assassination of Ii Naosuke in front of the Sakurada Gate of Edo Castle had taken place when there was snow on the ground. The phenomenon at work in presenting both incidents can be understood within the broader practice of building upon prior narratives or ideas through substitution, allusion and multiple meaning. Chfishingura had now become a sekai in its own right. Barbara Thornbury contemplates this fluidity of interpretation in her study of the Sukeroku plays, notably Sukeroku and the Thousand Cherry Trees. IMPRESSION S 26

- 19. Thornbury focuses on the practice of substitution, which she envisions in terms of plot and character "transformation": "The old order that which was fixed and idealized was renewed and regenerated through the new order, that which was newly developed and not yet perfected. As in the case of Sukeroku, the transformation was accomplished by means of the technique of double identity."'' In other words, later Sukeroku pieces reveal the main character to be Soga Goro, the archetypal revenge-taking character who figures in older narratives dating from the medieval period and in modern kabuki performances.39 The later plays rewrite Sukeroku's past to include the double identity of Soga Goro. Just as Sukeroku and Kanadehon chushingura settled within the formal and thematic parameters of other classic plays, Chfishingura prints took shape within the bounds of existing ukiyo-e print genres and turned the special characteristics of those genres to their own use. The very first Chushingura prints reflect the Kanadehon chushingura stage tradition and provide core reference material for later depictions. By the nineteenth century, Chu- shingura themes are found in landscape and topographical prints, warrior prints and even prints of beauties (bijin). 40 Through the juxtaposition of its verbal and visual conventions, a Chfishingura print appears to be set both on the stage and in Edo; the severed head, to belong to both Moro- nao and Kira. Even images of the retainers seem to portray both actors and the original samurai. In the nineteenth century, kabuki stepped forward to claim elements of the Chushingura tradition that had never before reached the stage, incor- porating them into new plays. Ultimately, however, support for Kanadehon chushinguraand its interpretive lens of the Taiheiki persisted despite the appearance of new versions: the eighteenth- century play became authen- tic in itself. Thus, among the astonishing variety of extant Chushingura prints, almost every work upholds the "loyalty" of the retainers with the celebratory air of that classic play. e This essay incorporates some images and The ukiyo-e collection of the Tsubouchi themes featured in "Chushingura on Stage and Memorial Theater Museum of Waseda in Print: An Exhibition of Books, Manuscripts, University (also known as the Waseda and Ukiyo-e" (Rare Book and Manuscript University Theater Museum), Tokyo, contains Library and Starr East Asian Library, Columbia one of the largest and most thoroughly University, NewYork, March 24 April 18, catalogued collections of Chushingura prints in 2003), organized by Henry 1). Smith II and the the world, with most dating from the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture, with nineteenth century. As a result of the mission the cooperation of the libraries of Columbia of the museum and the personal interests of University andWaseda University as well as the Tsubouchi Shoyo (i 8t9 1930), who conceived Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum, Waseda the institution and endowed it with his University, Tokyo. I would like to thank Henry personal librar), the prints in this collection Smith, Melissa McCormick, Yoshiko Oe, Julia were acquired with the primary aim of Meech, MathewThompson and David R. documenting kabuki performances and actors. Weinberg, as well as the participants of two The Theater Museum opened in 1928, when seminars led by Henry Smith at Columbia Tsubouchi, at the age of seventy, had just fin- University, on Chushingura (Fall 2 00i) and on ished his translation of the complete dramatic Edo culture (Fall 2003), for their contributions. works of Shakespeare. 40 FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 20. NOTES letters," but it is more likely that Jitsudo knew of other, secondary records of the Ako incident i. Stage prints produced for the dramatic (ibid., 4 ;2). While these may not survive, precursors to Kanadehon chushinguraare contemporaneous works with an impact on sometimes anachronistically referred to as later accounts of the incident were the manu- Chushingura prints, but in any case such prints script by Muro Kyuso (I6ý8 1734) "Ako gijin appear to have been few in number and did not roku" (Record of the righteous men of Ako) of constitute a coherent tradition. 1703 (revised 171 1; see note 14 below) and 2. In the words of Donald Keene, "The title Katashima Shin'en's Sekijo gishinden (Lives of calls attention to the coincidence between the the righteous retainers of Ako Castle), number of kana [in the Japanese syllabary] and published in Osaka in 1719 and subsequently the number of heroes who took part in the banned. vendetta"; Takeda Izumo, Miyoshi Shoraku and 7, Donald H. Shively, "Tokugawa Plays on The Treasury of Loyal Namiki Senryu, Chushingura: ForbiddenTopics," in James R. Brandon, ed., Retainers, trans. Donald Keene (NewYork: Chushingura: Studies in Kabuki and the Puppet Columbia University Press, 197 1), ix. I refer Theater (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, to the play as Kanadehon chushingurathroughout 1982), 23 57. to distinguish it from the general term "Chushingura" and to avoid confusion with the 8. Hiroaki Sato, trans., "Ko no Moronao: When other Chushingura plays that were produced in a Warrior Falls in Love," in Legends of the the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Samurai (Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook Press, 1995), 203. 3. For the historical incident, see Bito Masa- hide, "The Ako Incident, 1701 1703, "trans. 9. Prints which featured likenesses of specific Henry D. Smith II, Monumenta Nipponica ;8:2 actors but were not linked to any specific per (Summer 2003), 149- 7 o.The Chushingura formance were a type of mitate-e or stand-in story was known in English as the tale of the picture. In figs. 2a, 2b (acts 5 and 6), two of the "forty seven ronin" as early as A. B. Mitford's actors have been identified: IchikawaYaozo 11 Tales of OldJapan (London: Macmillan and Co., 0(733 1777) as Hayano Kanpei (figs. 2a, 2b), 187 1), I 49. The manifesto left at the mansion and Segawa Kikunojo III (17'1 1i8o) as of KiraYoshinaka after the attack bore forty- Okaru (fig. 2b), but they never performed seven signatures, but only forty-six turned these roles opposite each other in a Chushin- themselves in to the authorities. gura production as Shunko portrays them. See Waseda University Theater Museum, ed., 4. Recent scholarship, following Uchiyama Shibai-e zuroku 3: Chushingura (Catalogue of Mikiko, points toward Namiki Senryu as the theater prints 3: Chushingura) (Tokyo: Waseda main author of Kanadehon chushingura. See University Press, 1993), nos. 147 52; here Uchiyama, "Kanadehon chushingura no after Shibai-e zurok" 3. sakusha" (The author of Kanadehon chushingura), Kokubungaku kaishaku to kyozai no kenkyu i o. The 18o6 prints are the latest known (Studies in the teaching and interpretation of examples of Chushingura prints by Hokusai. Japanese literature) 31: 1; (Dec. 1986), ;8 66. For several earlier examples ranging in date See also Henry D. Smith II, "The Trouble with from 1790 to 1804, see Richard Lane, Hokusai: Terasaka: The Forty- Seventh Ronin and the Life and Work (London: Barrie and Jenkins, Chushingura Imagination," Nichibunken Japan 1989), 282. Additionally, the Edo Tokyo Review 14 (2004), 3-6;. Museum owns an oban triptych from Hokusai's Shunroperiod (c. 1779 93), Chushingura:The ;. Henry D. Smith II, "The Capacity of Night Attack (Chushingurayouchino zu); see Chushingura," Monumenta Nipponica 5 8: 1 Genroku ryoran (Genroku full bloom), exh. cat. (Spring 2003), 1 42. (Tokyo: NHK Promotion, 1999), 168,no. i i. 6. Federico Marcon and Henry D. Smith II, "A i i. Marcon and Smith, "A Chushingura Chfishingura Palimpsest: Young Motoori Palimpsest," 4;4 ;5. See also Smith, "Capacity Norinaga Hears the Story of the Ako Ronin of Chushingura," 23 24. from a Buddhist Priest," Monumenta Nipponica 58:4 (Winter 2003), 439 65.The oral 12. These figures were from the entries listed presentation that Norinaga recorded took place in B.W. Robinson, Kuniyoshi: The 3•arrior-Prints in Ise Province in the fall of 1744, four years (Oxford: Phaidon, 1982). In his 1996 foreword before the debut of Kanadehon chushingura.The to David R. Weinberg, Kuniyoshi:The Faithful preacher, Jitsudo, alluded vaguely to "Oishi's Samurai (Leiden: Hotei, 2000), 7, Robinson IMPRESS I ONS 2o

- 21. writes that within Kuniyoshi's total output of World: The JapanesePrint (NewYork: Dorset forty-five years, "at least twelve series and Press, 1978), 173, 204. twenty triptychs are devoted to the 23. Portraits of the Ako retainers in the form of Chushingura." ukiyo-e prints circulated with claims to visual 13. For further examples of prints in this fidelity. Examples are two oban series by category, see Genroku ryoran, 1i67 69. Kuniyoshi: Portraitsof the Faithful Samurai of True Loyalty (Seichu gishi shozo), 18g i, and True 14. See, e.g., Muro, "Ako gijin roku." An Portraitsof the Faithful Samurai (Gishi shinzo), undated manuscript copy of the 171 i version 18533. Robinson (Kuniyoshi, i;8) reproduces is housed in the Starr Library, Columbia prints from both series. For information on the University. Another copy of this manuscript portrait sculptures, see note 30 below. For is published in Nihon shiso taikei (Sources for eighteenth- and nineteenth century printed Japanese intellectual history), vol. 27 (Tokyo: materials devoted to the retainers, see Iwanami Shoten, 1974), 271 37o; for details Nakyama Einosuke, Zuroku chushinguragaho of the march to Sengakuji and the events (Catalogue: Chushingura pictorial) (Tokyo: taking place at the temple, see pp. 363 56. Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1999), ;8 63, 7 2- 7. 15. Takeda, Miyoshi and Namiki, Chushingura, 24. For a selection of actor prints of I80. nineteenth-century Chushingura plays, see 16. Bito, "The Ako Incident," 166. Shibai-e zuroku 3, 12 52. i7. Paraphrase in the words of Bito, ibid., 2;. B.W. Robinson writes that Lives of the Loyal 167. For more on Edo-period opinions of the Retainers "was printed and reprinted till the Ako incident, see James McMullen, "Con- blocks were worn out, it was endlessly fucian Perspectives on the Ako Revenge: Law imitated by Kunivoshi's pupils"; foreword to and Moral Agency," Mon umenta Nipponica Weinberg, Kuniyoshi: The Faithful Samurai, 8. 08:3 (Fall 2003), 293- 315. 26.While the 1847 48 Kuniyoshi series 18. Bito, "The Ako Incident," 16 . disguises the names of the individual retainers and substitutes the stage names for bishi and 19. For more information on censorship and the other main characters, the 1864 Kunisada Chushingura on stage, see Shively, "Tokugawa series publishes the true names (e.g., Kanzaki Plays on Forbidden Topics." Yogor6). While there were really no "laws" 2o. Henry Smith, personal communication. against using the real names of those who A woodblock-printed book preserved at participated in the Ako incident, a more or less Sengakuji, Exhibition of Sengakup Treasures at tacit understanding existed that the event the Temple Amidaoi in 18o8 (Bunko tatsudoshi involved the dignity of the shogun and hence Amidaji ni okeru Sengakup kaicho) with was to be avoided. The true names of Teraoka illustrations by Koriki Tanenobu (i yg6 183 i) Heiemon Nobuyuki and Sugenoya Sannojo records one such exhibition in Nagoya, Masatoshi, the characters mentioned above, where the book was published. Among the wereTerasaka Kichiemon Nobuyuki and Sugaya objects shown, most of which were related Han'nojo Masatoshi; they are found in early to the forty-seven ronin, were a set of forty- documents and manuscripts, e.g., Muro, "Ako six portraits of the loyal retainers and the gishin den" cited above, and appeared in print receipt for Kira's head. in the 18gos. A helpful name chart is provided in Ako-shi Somubu Shishi Hensanshitsu, ed., 2 i. Hiroshige designed aTakanawa landscape, Chushingura, vol. i (Ako: Ako City, Hyogo Complete View of Takanawa (Takanawa zenzu), Prefecture, 1987), 746 47. However, real for the oban triptych series Famous Places of the names and pseudonyms were often combined Eastern Capital (Tote meisho, 1832 34; i 836 or transposed intentionally or out of confusion: 42). Sengakuji does not appear, even though Kunichika's Lives of the Loyal Retainers of 1866 many other works in this series depict shrine uses a combination of real and disguised names and temple precincts. (e.g., SenzakiYagoro is a stage name for 22. Examples are Moonlight at Takanatva Kanzaki Yogoro). See Shibai-e zuroku 3, 82. (horizontal oban, c. 183 1, from the series 27. The characters in illustrations for gokan Famous Places of the Eastern Capital) and (extended picture book) fiction were also Returning Sails at Takanawa (horizontal oban, c. depicted as specific actors by members of the 1839 4o, from the series Eight Views of Shiba); Utagawa school. See Haruo Shirane, Early see Richard Lane, Imagesfrom the Floating Modern Japanese Literature:AnAnthology, 16oo- 42 FOXWELL: THE DOUBLE IDENTITY OF CHUSHINGURA

- 22. 19oo (NewYork: Columbia University Press, right to left, the actors listed are: Ichikawa 2002), 8oo-8oi. Shirane explains that the Danjuro IX ( 838 1903), Onoe Kikugoro V writer Santo Kyoden first adapted kabuki plots ( 844-1903), Nakamura Sojuror( 1835 to the g6kan format, adding depictions of 1889), Ichikawa Sadanji I (i842-1 9o4) and popular actors by UtagawaToyokuni I(1769- Ichimura (Bando) Kakitsu V (i 847- 1893) as 1825). Enya Hangan, and Sojuro, Danjuro, Kikugoro, Nakamura Nakazo III (i 809-i886) and Sadanji 28. See Hans Bjarne Thomsen, "The Other as 6boshiYuranosuke. No other copies of this Hiroshige: Connoisseur of the Good Life," print are known. The order of the names as Impressions 24 (2002), 48 71, fig. i i. In the they appear in the cartouche on the diptych Restaurants series, the figures portrayed appear may not correspond to the order in which the explicitly as portraits of actors. Each retainer actors appeared, a detail that has proved in the 1864 Lives of the Loyal Retainers is impossible to confirm; nor is it certain that the portrayed as an actor's likeness. The situation heads are attached in the correct order. resembles Kunisada's illustrations for books of fiction such as Nise Murasaki inaka Genji (A 3•. Loren Edelson, "The Ghost of Danjuro IX: country Genji by a commoner Murasaki, Still Haunting Kabuki," paper presented at 1829 42) by RyCteiTanehiko. While the "Rethinking Chushingura: A Symposium on the characters were Tanehiko's invention, Kunisada Making and Unmaking of Japan's National included visual clues suggesting that his Legend," sponsored by the Donald Keene illustrations of them actually depicted con- Center of Japanese Culture, Columbia Uni- temporary kabuki actors; see Sato Satoru, versity, NewYork, Mar. 30-3 1, 2003. "'Shohonsei'ni okeru gekijo shomei: Gekijo o 36. Ibid. nagarerufutatsuno jikan" (How theater sheds light on the production of scripts: The dual 37. Miyazawa, Kindai Nihon to Chushingura, 34. temporalities of the theater), Jissen bungaku 38. Barbara E. Thornbury, Sukeroku's Double 6I5 (Mar. 2004), I 20. Identity:The Dramatic Structure of Edo Kabuki 29. I thank Henry Smith for this suggestion. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies, 1982), 20. Sukeroku: Flower of 30. Miyazawa, Kindai Nihon to Chushingura,20- Edo (Sukerokuyukari no Edo zakura), a major 21, 30-32. play of the eighteenth century, represents the 31. New prominence is given especially to the heart of a tradition of "Sukeroku pieces." stage curtain. While it had long been a fixture in kabuki theater, knowledge of Western 39. Furthermore, early dramatizations of the dramatic conventions seems to have provoked Ako incident may have been set in the Soga a new awareness of it in the Meiji period; see "world" before being transferred to the world Samuel L. Leiter, ed., New Kabuki Encyclopedia: of the Taiheiki; see Keene, "Variations on a A Revised Adaptation of Kabukijiten (Westport, Theme: Chushingura," in Brandon, ed., Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1997), 384. Chushingura, 6. 3 2. Waseda UniversityTheater Museum, ed., 40. Kitagawa Utamaro (i 753 i8o6) produced Shibai-e ni miru Edo Meiji no kabuki (Edo and well-known bijinga representations of Meiji kabuki as seen in theater prints) (Tokyo: Chushingura; see ShugoAsano andTimothv Shogakukan, 2003), 108 Ii. Clark, The PassionateArt of Kitagawa Utamaro (Tokyo: Asahi Shinbun and London: British 33 The Shintomi-za was formerly known as Museum Press, 1 9 9 5 ).The variety of the Morita-za, one of the three main theaters Chushingura prints across genres was apparent of Edo along with the Nakamura-za and the in the Chushingura and Mitate ("Chushingura Ichimura-za. to mitate") exhibition held in Kyoto, 34. Because the leading roles were rotated Ritsumeikan University, Dec. 13, 2003-Jan. among the six actors, four of the actors had 16, 2004): http: / /www.arc.ritsumei.ac.jp/ the opportunity to play both Enya Hangan and events/o 3 1213 /degitalFrameset.htm OboshiYuranosuke, but on different days. From (accessed Apr. 2;, 2004). IMP RE S SI ON S 26

- 23. COPYRIGHT INFORMATION TITLE: The Double Identity of Ch|A-ushingura: Theater and History in Nineteent SOURCE: Impressions no26 2004 PAGE(S): 22-43 WN: 0400109618016 The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this articleand it is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. Copyright 1982-2006 The H.W. Wilson Company. All rights reserved.