Week 6 Rubens Medici Commission

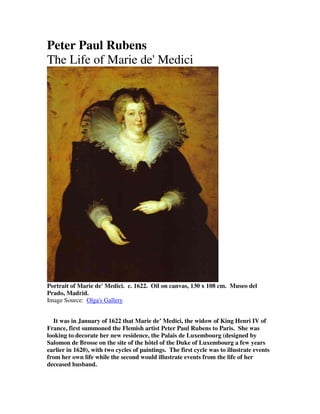

- 1. Peter Paul Rubens The Life of Marie de' Medici Portrait of Marie de' Medici. c. 1622. Oil on canvas, 130 x 108 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image Source: Olga's Gallery It was in January of 1622 that Marie de’ Medici, the widow of King Henri IV of France, first summoned the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens to Paris. She was looking to decorate her new residence, the Palais de Luxembourg (designed by Salomon de Brosse on the site of the hôtel of the Duke of Luxembourg a few years earlier in 1620), with two cycles of paintings. The first cycle was to illustrate events from her own life while the second would illustrate events from the life of her deceased husband.

- 2. Unfortunately for Rubens, the life of Marie de’ Medici was filled with overly melodramatic events, though none of these were particularly interesting. Born in Florence on April 26, 1573, the youngest daughter of Francesco I, Grand Duke of Tuscany and Johanna, Archduchess of Austria, Marie was considered to be a "handsome, vulgar, and heartless woman" (Bertram 104). Her uncle Ferdinando I de’ Medici, who had succeeded to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany following the death of her father in 1587, paid for her marriage to King Henri IV. This came in the form of six hundred thousand crowns, thus buying for her the Queenship of France. After their marriage in 1600 (Henri’s second following his divorce to Marguerite de Valois), "everything went wrong and their life became hell" (Avermaete 106). It was a quarrelsome and unhappy arrangement, encouraged constantly by the King’s vindictive and jealous mistress, Henriette d’Entragues. It is possible that Marie would have been a content and good-natured wife, but the daily bereavement she received from Henriette was enough to make her a sour, cold, and hateful woman. "At times there were open quarrels. The Italian woman knew how to give as well as take, and could be even more high and mighty than her King. His words may have been cutting, but she had a choice vocabulary of crude ones" (Thuillier 16). Their marriage was short-lived, however, for on May 14, 1610, the King was stabbed to death in the Rue de la Ferronerie in Paris. A mere two and a half hours after his assassination, Marie was recognized by the Parisian Parliament as the new Regent of France. The Dauphin, Louis XIII, had been born on September 27, 1601, and was thus only nine-years-old at the time of his father’s death. Marie would reign as Regent from 1610 until 1617, at which time Louis banished her for five years “in the wilderness,” otherwise known as the château of Blois. She was allowed to return to Paris with the aide of the Abbé de Luçon, later to become her enemy, Cardinal Richelieu, and she contented herself with the newly completed Palais du Luxembourg and its decoration. It can be assumed, however, that her desire to commemorate her life in such an extravagant way must have been centered around hidden motives. To be sure, she felt the need to reaffirm her political and/or her symbolic strength in the French monarchy, as she had always felt slighted by her son due to his abrupt termination of her Regency (which she had anticipated lasting quite a bit longer than it actually did). Through the commission itself as well as the final product, the Queen was able to establish herself as a valued member of the royal family, despite her permanent banishment in July 1631 to Compiegne. Rubens' first visit to Paris would last for six weeks, during which time he was lodged near the Pont Neuf on the Quai Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois. The visit was only intended to be a preliminary discussion of the details of the commission, but Rubens kept himself busy with a variety of activities. Among these, he inspected the palace where the cycle was to be displayed and painted portraits of Marie and Anne of Austria, whom Louis XIII had married at the age of fourteen in 1615. The Queen's advisor, Claude Maugis, Abbé de Saint-Ambroise, led the negotiations for the cycle and was an ardent supporter of Rubens' ability to carry out such an enormous task. "He publicly declared that 'two painters of Italy would not carry out in ten years what Rubens would do in four, and would not even think of

- 3. undertaking pictures of the necessary size'" (White 56). It was decided and agreed by all parties that Rubens would complete the two cycles of paintings (thus the decoration of two full galleries in the Palais du Luxembourg) for a price of twenty thousand crowns. The cycle of the Life of Henri IV was never undertaken, though the Life of Marie de' Medici was completed in full. There were twenty-four paintings in all, including portraits of the Queen and her parents. The other paintings are as follows: The Destiny of Marie, The Birth of Marie, The Education of Marie, The Presentation of the Portrait, The Marriage by Proxy, The Debarkation at Marseilles, The Entry into Lyons, The Birth of the Dauphin, The Consignment of the Regency, The Coronation of the Queen, The Death of Henri IV and the Proclamation of the Regency, The Council of the Gods, The Triumph at Juliers, The Exchange of Princesses, The Felicity of the Regency, The Coming of Age of Louis XIII, The Escape from Blois, The Treaty of Angoulême, The Conclusion of the Peace, The Full Reconciliation, and The Triumph of Truth. Indeed, the commission was to be one of the most difficult that Rubens would ever undertake, as he not only had to conform to extravagant spatial requirements, but he was also painting the cycle in a tense political arena for an uncompromising monarch. "Apart from these difficulties of poor subject and large space, Rubens had to suppress much in the life of Maria so that he might not offend her, and so to handle what he selected that he might not offend the King. Realism, in other words, would have been most dangerous" (Bertram 110). Therefore, how did Rubens go about representing the rather unfascinating and extremely complicated life of such an infamous Queen? In what ways was he able to incorporate both touchy and hurtful subjects into the overall celebration of her existence? To what limits did he stretch his imagination in order to envison extravagant depictions of mundane events over and over? It is indeed true that "considerable imagination, aided by an abundant use of classical allegory, was necessary to present the quarrelsome heroine as the embodiment of all the virtues" (White 56-57). Therefore, in almost all of the paintings that make up the cycle, the Queen is surrounded by allegorical figures as well as those from ancient mythology. "The gods, goddesses, and other allegorical figures who accompany the queen throughout the different events of her life raise her into a sort of empyrean situated somewhere between earth and sky. Thus rather humdrum facts take on the aspect of an apotheosis, in perfect accord with the idea of 'royalty by divine grace'" (Badouin 183). The final result of the cycle was an intentional and successful façade that disguised the true historical facts. In examining seven of the twenty-four paintings in the cycle, one is able to best understand the very unique ways in which Rubens communicated the life of the difficult, complicated, but extremely fascinating Marie de' Medici.

- 4. The Destiny of Marie de' Medici. 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 12' 11 1/8" x 5' 1". Musée du Louvre, Paris. The Triumph of Truth. 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 12' 11 1/8" x 4' 11". Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image Sources: Olga's Gallery These are the first and last paintings in the cycle (excluding the three portraits of Marie and her parents). In The Destiny of Marie de' Medici, Rubens has depicted the Fates, spinning the destiny of the unborn Queen while Zeus and his wife Hera watch from above. The Fates, otherwise known as the three Moirae, were female deities who supervised fate rather than determined it. The daughters of Zeus and Themis, they included Clotho (who spun the thread), Lachesis (who measured the

- 5. length), and Atropos (who cut it). It is interesting to note here that the scissors of Atropos were omitted in order to stress the privileged and immortal character of the Queen's life. The Triumph of Truth is an ambitious end to the cycle, as it depicts King Louis XIII and Marie finally reconciled and seated in the heavens. The King presents a laurel wreath to his mother which surrounds two joined hands with a heart above them. Rubens purposefully depicts Time uncovering Truth below the pair, as the misunderstanding between Louis and Marie was due in part to false reports from others. The Education of Marie. 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 12' 11 1/8" x 9' 8 1/8". Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image Source: http://sunsite.icm.edu.pl/cjackson/rubens/rubens46.jpg

- 6. The Education of Marie includes an abundance of allegorical and mythological figures, who all aide in the schooling of the young Queen. To the left, Apollo (the patron god of arts), Athena (the goddess of wisdom), and Hermes (the messenger of the Olympian gods), teach her music, reading, and eloquence respectively. At the same time, the three Graces (or Charities) are present at the right to offer her beauty. As ancient Greek divinities for beauty, grace, and artistic expression, the three sisters of the Graces included Euphrosyne, Aglaea, and Thalia. The Debarkation at Marseilles. 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 12' 11 1/8" x 9' 8 1/8". Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image Source: Web Gallery of Art

- 7. In The Debarkation at Marseilles, Marie is welcomed to her new home by a personified France, wearing a helmet and a blue mantle with golden fleur-de-lis. Above, Fame blows two horns to announce her arrival to the people of France (including her future husband). Below, Neptune, three sirens, a sea-god, and a triton help escort the future Queen to her new home. To the left, the arms of the Medici can be seen above an arched structure, where a Knight of Malta stands in all of his regalia. On a side note, Avermaete discusses an interesting idea that is particularly present in this canvas. "He [Rubens] surrounded her [Marie de' Medici] with such a wealth of appurtenances that at every moment she was very nearly pushed into the background. Consider, for example, the 'Disembarkation at Marseilles', where everyone has eyes only for the voluptuous Naiads, to the disadvantage of the queen who is being received with open arms by France" (Avermaete 107). The Coronation of the Queen. 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 12' 11 1/8" x 23' 10 1/4". Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image Source: http://cgfa.sunsite.dk/rubens/rubens2.htm This painting is one of the few in the cycle that does not contain any mythological or allegorical figures. It also is an accurate depiction of an historical event in the life of the Queen, as the King had the Queen crowned at the basilica of Saint-Denis in

- 8. Paris to increase her authority on May 13, 1610 (the day before he was assassinated). The Death of Henri IV and The Proclamation of the Regency. 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 12' 11 1/8" x 23' 10 1/4". Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image Source: Web Gallery of Art In this painting, Rubens combines two subjects (related though they are) into one scene. On the left, the King, assassinated by a madman, is lifted to the heavens by Time where he is received into the arms of Zeus. To the right, the Queen is dressed in mourning clothes and is seen seated on a throne. To her right stands the goddess Athena, representing Prudence, and in the air a woman holds a rudder, representing the Regency. The Queen accepts an orb, a symbol of government, from the personification of France while the people kneel before her. This is an appropriate example of the exaggeration of facts in the cycle. Rubens stresses the idea that the Regency was offered to the Queen (the populace almost seem to be begging her to accept the offer), though she actually claimed it for herself the same day her husband was murdered.

- 9. The Council of the Gods. 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 12' 11 1/8" x 23' 10 1/4". Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image Source: http://www.artunframed.com/rubens_3.htm The Council of the Gods is one of the least understood of the paintings that make up the cycle. It is meant to represent the conduct of the Queen and the great care with which she oversees her Kingdom during her Regency. Thus, how she overcomes the rebellions and the disorders of the State. However, it is difficult to make out the subject matter of the work, as the scene is packed with a variety of mythological figures. These include Apollo and Pallas, who combat and overcome vices such as Discord, Hate, Fury, and Envy on the ground and Neptune, Pluto, Saturn, Hermes, Pan, Flora, Hebe, Pomono, Venus, Mars, Zeus, Hera, Cupid, and Diana above. In the end, Rubens accomplished quite an amazing feat. He completed a total of twenty-four enormous paintings in only three short years. He, unfortunately, did not look back on the experience as a positive one. "In retrospect, in his own country, Rubens was calmer but hardly less bitter, 'when I consider the trips I have made to Paris, and the time I have spent there, without any special recompense, I find that the work for the queen mother has been very unprofitable to me'" (White 62). Marie de' Medici, however, was overjoyed at the final product. But then again, who wouldn't be? "Rubens was so kind to the queen, and adorned her with so many imaginary graces, that Marie de Medici was beside herself with delight. That,

- 10. of course, is the way in which the great ones of this world want history to be written" (Avermaete 107). Bibliography Avermaete, Roger. Rubens and his times. Cranbury, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1968. Baudouin, Frans. Pietro Pauolo Rubens. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1977. Bertram, Anthony. The Life of Sir Peter-Paul Rubens. London: Peter Davies, Ltd., 1928. Thuillier, Jacques. Rubens' Life of Marie de' Medici. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1967. White, Christopher. Rubens and his world. London: Thames and Hudson, 1968.