Studio são paulo magazine eng hq

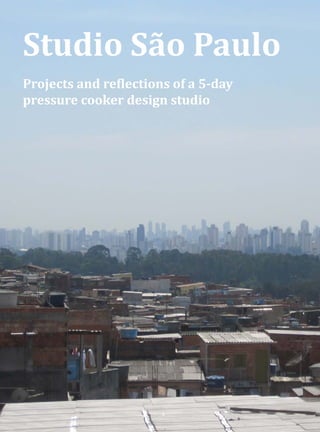

- 1. Studio São Paulo Projects and reflections of a 5-day pressure cooker design studio

- 2. Studio São Paulo 2 The proverbial egg for Studio São Paulo was laid in the Netherlands, amongst five offices in strategic urban planning and design. In the Netherlands they often meet eachother in competition entries where they dispute each other for projects. The people know eachother a bit and in fact admire eachother often for their inventivenes. Although from different sizes and ages, the offices share the ability to think though the scales in strategic plans. The neutral context of São Paulo provided a great opportunity to get to know eachother better. All participating offices had some links to Brazil and São Paulo especially. Be it professionally, academically or personally. With this idea of close collaboration and open exchange of thoughts Studio São Paulo started. We agreed that the best way to really understand the contemporary challenges for any city is in a hands-on way. In other words: collaborating to work on actual questions. Studio São Paulo by Jaap Klaarenbeek Jaap Klaarenbeek and Rogier van den Berg visited São Paulo in May 2011 to meet people from various governmental institutions, ministeries, universities, developers and urban design offices. Ultimately, three cases were set up in collaboration with four of São Paulo’s municipal departments: SEHAB/COHAB, SP Urbanismo, SMDU and the Secretario de Verde e Meio Ambiente. Together the cases on the historical center, brownfields and peripheral ‘fundos de vale’ give a broad insight in the urban dynamics of Sao Paulo today. Studio São Paulo worked on all three cases with the ambition to think together about integrated planning strategies. For each of the three typical cases Studio Sao Paulo searched for specific solutions that can be exemplary for approches in other parts of the city, and hopefully, maybe even translated to enrich the Dutch practice. Three formidable Paulistan offices joined Studio São Paulo to complete the team. With a high spirit of collaboration and exchange Studio São Paulo took off. Early October 2011 five Dutch and three Paulistan urbanism offices participated in Studio São Paulo. In a pressure cooker design studio Studio São Paulo combined experience and creative urban thinking of both sides of the Atlantic to generate inventive concepts for several contemporary urban challenges in São Paulo in which social, economical and ecological issues converge in spatial cases. This booklet presents a concise report of Studio São Paulo, with an introduction, presentations of the cases and personal reflections. We agreed that the best way to really understand the contemporary challenges for any city is in a hands- on way. In other words: by collaborative work on actual questions.

- 3. Studio São Paulo 3 Content Studio Sao Paulo 2 by Jaap Klaarenbeek How to read (Summary) 4 by Jaap Klaarenbeek NL meets São Paulo 6 Two changing urban planning paradigms Three Cases for Studio São Paulo 8 Center, Brownfields, Periphery Case 1: Innercity Rejuvenation 10 From individual buildings to urban thinking Case 2: Brownfields; Heliopolis & Vila Carioca 14 From Housing to City Case 3: Periphery and ‘fundos de vale’ 18 Pro-flow Sao Paulo moving in the right direction 22 by Gert Urhahn Making cities for people 24 by Ricardo Correa Sticky as a Brigadeiro 25 By Kria Djoyoadhiningrat Ordem e progresso 26 by Matthijs Bouw, Han Dijk, Bart Aptroot São Paulo complete, sometimes forgotten 30 by Heidi Klein São Paulo Downtown Re-occupation 32 by Renata Semin On public value 34 by Bernardina Borra, Gert Urhahn, Luis Pompeo, Tiago Oakley Housing as a driver for good public space 38 by Rogier van den Berg Screaming vacancy 40 by Bart Aptroot A permananent Studio São Paulo? 42 by Jaap Klaarenbeek & Kria Djoyoadhiningrat Colophon 46

- 4. Studio São Paulo 4 Studio São Paulo magazine introduces the main drives and ideas behind Studio São Paulo, presents the cases, draws reflections and makes a proposition for a continuous Studio São Paulo. In a first article Jaap Klaarenbeek discusses what we embarked for to learn from São Paulo. This is followed by a short introduction of the three cases and the descriptions of the projects developed during the five-day workshop. The team for case 1 – the city centre - proposes a placemaking strategy for rehabilitationg of the city center, and advises SEHAB/COHAB to use their powerfull tool of buying and refurbishing houses, not on the currently used basis of costs-effectiveness of the individual refurbishments, but ‘think more urban’ in the selection of where to refurbish. Working on the Petrobras site near favela Heliopolis, the team for the second proposes to preserve large part of the still empty site as a park and to ‘make city, instead of housing’. This way valorizing the green and desifying the nearby Vila Carioca with social housing integrate in the neigborhood. The team working on case 3, the Jaçu-Rio Verde valley, noticed that the Secretario’s strategy to transform some of the clogged up waterways into linear parks is very difficult to execute. They are planned as a masterplan but not phased in such a way. In their view focus should be on the linear and not on the parks, making networks. They propose to create a planning logic that is phased in interconnected sections. The surrounding city adopts and creates these sections. The network combines it. The second part of the booklet complements the projects with personal reflections and experiences. First, Renata Semin presents the ideas of her office Piratininga arquitetos on how to apply the thoughts/strategies generated during Studio São Paulo for the entire central region. Gert Urhahn (Urhahn Urban Design) reflects on being back in São Paulo after 15 years, and makes a hopeful comparison between positive urban change in Amsterdam and São Paulo. Matthijs Bouw (One Architecture) and Han Dijk (POSAD) reflect on how current local, opportunistic and short term projects can be thought such that they will contribute to the long term planning goals for the city. In a joint article Urhahn Urban Design and 23sul arquitetos dwell on how to create public value using ‘open development’ working cooperative and user oriented. Heidi Klein urban culture around the Anhangabau valley. Rogier van den Berg explains how housing guidelines can lead to better and more accessible and secure public space. Kria Djoijoadhiningrat (Studio ROSA) takes a lesson to the Netherlands from the ‘upside down’ planning of the Paulistan bycicle network. How ‘just doing’ can generate a culture shift, responsibility and public participation. Ricardo Correa, director of TC Urbes, makes a case for more international design collaboration, as well as a general call to his Brazilian colleagues for more collaborative design that included users in the design phase so as to get more consensus, mutual understanding and better plans. Finally, Bart Aptroot calls for crowd-sourcing and idea competitions to generate good examples and set positive change in motion. The report concludes with a joint call for Brazilian ‘makers of the city’. A call for a continuous Studio São Paulo. How to read (Summary) by Jaap Klaarenbeek

- 6. Studio São Paulo 6 The Dutch have a long history of urban planning and design. Brazilians in turn do not have a typical urban planning or urban design culture. Yet, they do have a lot of urban. Most of Brazils city’s –and São Paulo expecially - have gone though such an urban explosion that the city continously superceded almost every attempt to planning or design. But times are changing... In the Netherlands the planning frenzy of the 90’s and begin of the 21st century has come to a hold as a combined result of a cultural shift in thinking about planning and financial downturn. VINEX-neighborhoods, the large scale urban expansions of the 90’s, are receiving critiques for being much too focussed on residential purposes only. Post-war housing neighborhoods, on their turn, are asking for attention due to current social problems. Their mono-functional planning attracted a thin socio- economical layer of society. Dutch urban planners and designers are searching how to create more diversity and freedom of private companies and individuals to build and use their plot as they wish. To build more socially, economically and ecologically resilient cities. At the same time budgets are tightening and government is withdrawing as the one and only strongest agent in urban planning. With smaller budgets the Dutch planning practice is searching how to generate wished effects with cheaper and more focussed interventions. Illustrative is the renaming of the former ‘Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and Environment’. With its new name as ‘Ministry of Infrastructure & Environment’ the ministry has lost its direct reference to the spatial dimension and will in the future only focus on those spatial plans essential to sustain the economical carriers of the Netherlands (and those themes that are considered as national interest). A radical paradigm shift. While the Dutch planning pratice is weakening urban planning and design in Brazil are on the rise. NL meets São Paulo: two changing urban planning paradigms by Jaap Klaarenbeek While the Dutch planning pratice is weakening urban planning and design in Brazil are on the rise.

- 7. Studio São Paulo 7 Blessed with an economical tailwind and a flattening populational growth, popular and political conviction to diminish the dire social differences in São Paulo seem to have grown stronger than ever in recent years. This hasn’t resulted in the instant disappearance of problems. Off course not. Challenges remain big. But the current situation at least allows the possibility to take a breath and think. For the first time in decades, maybe even since a century, there are possiblities to plan improvements instead of ad hoc problem solving urban ‘planning’. For whoever visits the city concequences of the convitions to improve the city are visible everywhere; in- and outside of the planning offices. The new Rodoanel, brand new metro stations, a new centre in the east around the new World Cup stadium, SEHAB’s impressive urbanization and social housing efforts, innercity rejuvenation plans, participative planning experiments, new bus corridors, ambitious plans for parks and cycling routes. The ‘Plano Estrategico Director’, the strategic masterplan of the city binds together the most important plans for the city’s future. During the conversations in our preparation visit we found that from the Dutch perspective it was difficult to see the city’s strategical masterplan as an ‘integrated plan’. Essentially, the plan is a collection of juxtaposed partial plans. The one plan laid over the other. In practice – we understood – the plan sometimes becomes a virtual declaration of war between municipal departments as social housing, mobility and environmental projects are planned on the same spot. Without a matched/balanced vision. Result? The bulldozer of the one department literally driving into the bulldozer of the other department. ‘São Paulo has a lot of plans, but no vision’ we heard from others. During the various preparational conversations, we were in fact slightly requested to force collaboration between the departments during the workshop to see if we could make small attempts to reach ‘real’ integrated plans. All in all, the call to focus the Studio São Paulo workshop on integrated planning essentially was pushed forward during the meetings with the Brazilians we spoke during our preparation visit. So, while Dutch are trying to escape their self-created stranglehold of public planning in seach for more freedom of private initiatives and São Paulo is alingning fragmented dreams, plans and hard political targets to reach a more effective and balanced urban planning framework, we met in Studio São Paulo to see what these worlds could learn from each other. During the various preparational conversations, we were slightly requested to force collaboration between departments during the workshop to see if we could make an attempt to make ‘real’ integrated plans.

- 8. 1 2 Studio São Paulo 8 Case 1 Innercity Rejuvenation The historical Center, focusses on new strategies how to redifine Sao Paulo’s historical city center. Although many subcenters have popped up during recent decades, the historical center still is a very strong centrality. It remains the strongest pole for commerce and business. It is the cities major transport hub and location of governmental departments and institutes. Yet, by many Paulistans the center is seen as a dangerous place which is desolate at night. The center hosts thousands of derilict and empty buildings. Although it is well connected, it has to cope with enormous problems of congestion. There is a strong informal trade, while large scale speculations impede large scale refurbishment and facelift of the center. What is the ambition? What are the currently applied projects and strategies? Are they able to start the process of regeneration? Who are the actors and what can be their role and benefit? How can we bring back an all day accessible center for all Paulistans? Three cases for Studio São Paulo by Jaap Klaarenbeek Studio São Paulo selected three cases to work on during the October 2011 workshop. Together the cases on the historical center, brownfields and periphery give a broad insight in the urban dynamics of Sao Paulo today. Studio São Paulo worked on all three cases with the ambition to think together about integrated planning strategies. For each of the three typical cases Studio Sao Paulo aimed to come to specific spatial solutions that can be exemplary. Case 2: Brownfields – New Center Large tracts of industrial zones that are located strategically along the north- south railway lines are coming available for development. São Paulo has the ambition to intensify these areas for thousands of Paulistans to live. But how to steer and stimulate this process? How can this barrier sew the central and east São Paulo together and can the area become more than just a ‘collection of profitable lots along the railway’. The brownfields along the railway lines now occupy strategic positions within the urban field. They are potential

- 9. 3 Studio São Paulo 9 Case 3: Periphery - Fundos de Vale The third case focusses on the integrated development of a linear park in the vast eastern periphery of São Paulo. The so called ‘fundo de vales’, or translated in English, the lower valleys, are omnipresent in Sao Paulo. The valleys pose important challenges all over Sao Paulo. As the lowest points in the landscape, they are the natural locations for streams and rivers. Due to intensive urbanization, many of these streams have become the locations for (large scale) infrastructure. At some places the ‘fundos’ are not yet canalized and beautifull nature is still to be found there, but most other stretches are occupied by dwellers that live in precarious housing along polluted streams. This leads to enormous problems during rainfall when the water rises and the city’s main infrastructure becomes clogged. The ‘fundos’ could be attractive public linear parks within the dense urban pattern of São Paulo as the municipality envisions them. But how to get there? Rethinking their potential as integrated arteries for green space, leisure and as a public central area is central in this case. Especially the definition of a strategy on ‘how to get there’ seems important, as making green seems largely a social challenge. subcentres between the innercity and the periphery. We focus on the Petrobras site. Located about eight kilometers from the city center and close to Sao Paulo’s biggest slum Heliopolis. What will be the urban mix that could be both be attractive for new investments and citizens as well as provide an additional urban quality and services to neighbourhoods surrounding the site. The brownfield condition could be a testbed to test scale, connectivity and new typologies as an example for other brownfield operations.

- 10. Studio São Paulo 10 While São Paulo’s historical city centre currently is predominantly a CBD, it is still in the historical, geographical and cultural heart of the city. There are many public projects in the city dealing with crime or vacant buildings or heritage protection or the quality of the public space, showing a direct implementation of political goals: less vacancy, more social housing, safer public space. In our workshop the focus was on a project run by COHAB, whose aim was to transform vacant buildings into social housing. To be successful in a relatively short time COHAB aimed at those buildings that allowed for the fastest and best manageable transformation. The pace and quantitative success of COHAB deserve encouragement. But it appears to be just that, an immediate and concrete translation of a political goal to the smallest scale of a single building, without a connection with the overall agenda: to make the centre an inclusive city. What the city centre needs is urban thinking. An interaction between structural, infrastructural, social and economical issues which works on an intermediate level, between politics and concrete projects. During the workshop we analyzed the city centre to find possible sites for a strategy that works on the intermediate scale: a place making strategy. After some data crunching (building vacancy, networks, employment, education facilities and a fear map) we found two possible areas that have the right mix: Avenida Sao Joao and Praca da Sé. Given the limited time we focused on the first. In a process of exchanging local and international examples, fact finding and critical interrogation we defined the following ingredients: Add a serious amount of housing. The COHAB program for transforming vacant buildings into social housing could be used as a tool for that. But also use the opportunities that From individual buildings to urban thinking Case 1: Innercity Rejuvenation Project group Matthijs Bouw Bart Aptroot Renata Semin José Armenio Brito Cruz Marlon Longo, Heidi Klein Assistance Rodrigo Tanaka Aline Friguereido

- 11. Studio São Paulo 11 Studio SP Survey: fear !"######$%&'&#(&#)*+,-./0Ӓ&%*5 6"######7&*8&9:#(*#7&;+:2#-4/.(/9< ="######>8?./&#-4/.(/9<#1-*.@*(*%*5 A"######7:+&9#-4/.(/9< B"######CD*&8*%2#%:E F"######G:0/*(&(*#(*#74.84%&#H%8I28/0&#D&.. J"######K&%&<4?#D:8*.#8D*&8*% L"######M?%/:#(*#H9(%&(*#;49/0/+&.#./-%&%N O"######7/8N#7:490/. !P"##GQ:#R%&90/20:#S&E#20D::.#&9(#0D4%0D !!"##M*8%:+:./8&9#0&8D*(%&.#&9(#GT#G34&%* !6"##GQ:#$&4.:#S&E#7:4%82 !="##R/%*#-%/<&(*#D*&(34&%8*%2 !A"##U%(*;#=V#(:#7&%;:#7D4%0D !B"##$:4+&8*;+: !F"##$&%34*#W:;#$*(%:#-42#8*%;/9&. !J"##$?8/:#(:#7:.T</:# #######10/8N#X:49(&8/:9#D/28:%/0&.#2/8*5 !L"##>;+*%/&.#+*%/:(#D:42*2 !O"##GQ:#$&4.:#G8:0Y#M&%Y*8 6P"##7/(&(*#(*#GQ:#$&4.:#Z&9Y#-4/.(/9< 6!"##M&%8/9*../#-4/.(/9< 66"##GQ:#Z*98:#G*;/9&%N 6="##$&/22&9(4#23#&9(#0D4%0D 6A"##U./(:#<&..*%N 6B"##M49/0/+&.#8D*&8*% 6F"##GD:++/9<#7*98*%#S/<D8 6J"##)&;:2#(*#H[*@*(:#23 6L"##$&8%/&%0&#G3 6O"##Z&90:#(:#Z%&2/.#74.84%&.#7*98*% =P"##7R#74.84%&.#7*98*% =!"##H%8*2#G34&%* # H"####]/&(48:#(:#7D?#^#$&8%/&%0&#G34&%* Z"####GQ:#K:Q:#H@*_ 7"####]/&(48:#G&98&#>X/<`9/&# W"####GQ:#K:Q:#a#>+/%&9<&#&@*_ ! 6 W 6A 6J 6F H Z 7 66 6! 6P !O 6O !J !L =P !! != !6 !PO 6L L J F B A = !A !B !F 6= 6B =! Studio SP Mapping: important places in off-hours Studio SP Two systems 8 ¥ Walking through the city, the rate of underutilized buildings (also ofÞces) seems extreme: is there not simply too much building mass (in relation to accessibility, parking, infrastructure, quality, etc.)? ¥ Can the CBD support mix?

- 12. Studio São Paulo 12 existing buildings offer. Loft spaces, roof terraces, and mixed use buildings can create a rich mix of housing to attract the young professionals. More parking will be required to facilitate the new residents. Because even while public transport in the centre is good, to reach the rest of the city the car is still the preferred way to go. Make safe areas of manageable size and shape and make a safe connection to the nearby metro station. Improve the square by linking it better with the plinth program. Program the pedestrian area with smaller and larger activities, for example terraces on the pedestrian areas during lunch and dinner time, festivals in the connecting Parque Anhangabaú. Introduce street management to get the property and store owners actively involved, sharing the responsibility of a safe and lively street, getting the right mix of program. Coalitions should be built, for example between the businesses in Sé and the stores, bars and dining places along rua Sao Joao. Finally, spread the word. Brand the succes, let it expand to neighbouring streets or leapfrog to other new hotspots in the centre. Studio SP 30

- 13. Studio São Paulo 13 The current strategy appear to be an immediate and concrete translation of a political goal to the smallest scale of a single building. without a connection with the overall agenda: to make the centre an inclusive city. What the city centre needs is urban thinking.

- 14. Studio São Paulo 14 Knowing that the destiny of the Petrobras area is on its way to implementation, we used it as an inspiration to think about a new piece of the city. We looked at the area as an experimental field for how to tackle the urban fabric in Sao Paulo to become a more sustainable “part” of the city that can be stronger and more self-reliant based on its inner structure and existing qualities. The un-built space of Petrobras, clamped in between Heliopolis and Vila Carioca – a poor neighbourhood and a mixed industrial and housing area- is included within two apparently different Urban Plans. On the one hand, the housing plan of Heliopolis is in dire need to deliver 5000 new housing units as soon as possible. And on the other hand the Urban Operation Mooca-Vila Carioca that foresees infrastructural improvements, programme mix, densification, and an increase of public transport along a commercial corridor. Walking through the area we could feel how Heliopolis is an improving neighbourhood, with lively streets and a strong sense of community. Awareness of people is rising, and most probably their demands and desires in a few generations will be far evolved. On the other side, Vila Carioca is already a mixed use neighbourhood well connected to the new metro station of Tamanduatei. Its fabric is quite structured in a well functioning grid of streets, with buildings from one to a maximum of four storeys. There are schools, some shops, community facilities, several working places. The area still has plenty of room to increase density and optimize land use within the existing structure. The common point between the two areas – Heliopolis and Vila Carioca- is the lack of urban spaces. The street is the unique means of connection for cars, buses, and people, as if they were of the same nature. Collective space is sacrificed with refuge only found in the accidental left over places. Yet, the site of Petrobras conceals behind its walls a valuable hilly green area. All local evidences points towards a potential osmosis of urban demand and supply between the Urban Operation and Heliopolis. After a quick sketch calculation we figured out that filling out the gaps and vacancies of Vila Carioca, the housing needs of Helipolis could be accommodated within its existing fabric. When these ambitions are put within a more integrated relationship - to create the maximum of high quality spatial coherence, public value, housing, working, recreation, and other functions and you’ll get a fully fledged piece of city. As a starting point the public value of Petrobas’ hill as a park connecting Helipolis, Vila Carioca and the metro is of critical importance for the future of both areas. From Housing to City Case study 2 brownfields: Petrobras Petrobras´ hill is of critical importance as a park and connection Case 2: Brownfields Project group Gert Urhahn Bernardina Borra Daniela Getlinger Rogier van den Berg Jaap Klaarenbeek Luis Pompeo Martins Tiago Oakley Assistance Andre Kwak Vanessa Padia Marcelo Rebelo Fernando Gasperini

- 16. Studio São Paulo 16 Opening up a park and enhancing small interventions in the adjacent areas would foster a social mix, create a clear routing towards the metro, provide a mix of housing on the edges and allocate public services. Following this path could also help job creation in Vila Carioca, as well as allow differentiation in housing typologies along the edges of the park, or into empty plots to be implemented in Vila Carioca. Eventually this would increase the financial and urban value for the land and of all the activities in the surroundings areas. The actions to be taken in Heliopolis are -of course to relocate unsafe and unhealthy housing units, improve infrastructure and open spaces, to then legalize ground and housing properties. Contemporary to this in Vila Carioca the task would be to increase the density of working places and warehouses - freeing up plots to build small services, pocket spaces, new social and private housing while fitting the existing into a maximum of four/five floors along the streets, and ten in the interiors of the block. Around the station a pole with a privately developed mix of housing and offices could also help financing the plan. The strip along the railway for industry could be densified in use, and adapted as a flood barrier. Additional room for housing could perhaps also be found in the areas south-east of Petrobras. This could lead to a diversified neighbourhood, not alienated in condensed social housing monolithically built at once, but grown in a more organic process taking the positive aspects of how Heliopolis and Vila Carioca did in their turn. It could further help to avoid future social discontent -the likes of which have been seen in the peripheries of European cities, see for instance the ravages of the Banlieus in Paris, or the famous no-go areas in cities like Naples. Socially mixed and qualitative neighbourhoods as Cuidade Tiradentes in Sao Paulo, or Jordans in Amsterdam should be considered as paradigms to achieve. This procedure would imply an open process in phases were SP Municipality plays the initiator role for: - establishing the park, perhaps in collaboration with the private sector e.g SESC - delineating its edges for social housing, and private developers under certain conditions - stimulate and guide land use optimization of Villa Carioca. The municipality - sehab- cohab- town planning- should be the moderator between social interests, the legal and still illegal owners of the land, private developers, the local inhabitants and workers. Fostering Public Value collective green + services financial value clear routing jobs creation differentiation in housing typologies social mix the motor

- 17. Studio São Paulo 17 Heliopolis Relocate unsafe and unealthy housing units Improve open spaces Legalize ground and housing properties from Housing to City Vila Carioca Densify working and warehouses Social housing capacity c.a. 2000 units: 4floors along the streets 10 floors in the interior of the plot create a pole around the station with private developments use the strip along the railway for industry adapted as flood barrier open up for small pocket spaces Park Attractive urban collective green + facilities Connection from Heliopolis to the hub across Vila Carioca Housing capacity on the edges: c.a. 500 social housing units c.a. 1000 middle class private developments Additional social housing capacity for c.a. 2500 units

- 18. Studio São Paulo 18 Parque Linear Rio Verde: The transformation of a valley in the densly populated Eastern part of the Metropolis. This project is directly related to the larger challenges regarding the water problems of Sao Paulo. In the rapid development of the city, the most crucial infrastructural connections are located directly next to or right on top of the streams and rivers in the lowest levels of the valleys. At these points lots of informal housing is built, in the form of favelas and structures, realised without a building permit inside the flood areas. The Secretario de Verde e Meio Ambiente uses the strategy of so-called linear parks in these areas. The goal is to thereby control the water issues while creating valuable public space at the same time. Because the area is divided in many smaller plots with complex situations of ownership, the project is cut into segments that are being realised one by one. This segmentation could be an opportunity for development, rather than an obstruction. The project proposal of studio Sao Paulo combines three strategies. The first is to implement the linear connection at the start of the project. This area should serve as a connection for local traffic of pedestrians and cyclist, separated from the car infrastructure. A bicycle path can be realised along the stream where possible and if the area along the stream is not accessible yet, the path should have a temporary place along the road on either side of the stream. This gives the inhabitants a fast connection to the public transport and the larger park and it makes the vacant areas of the riverside accessible. Obviously this leads to confrontation with the pollution found there, but we believe Pro-flow Case study 3 periphery: Itaquera Case 3: Periphery & Fundos de Vale Project group Han Dijk Emile Revier Kria Djoyoadhiningrat Daan Zandbelt Laetitia Lemos Ricardo Correa Taissa Cruz Assistance Ana Bádue Ramiro Levy

- 19. Studio São Paulo 19 1 2 3 The first step is to implement the linear connection at the start of the project. This should serve as a connection for local traffic of pedestrians and cyclists.

- 20. Studio São Paulo 20 that it could have the same effect as the phrase “Tiraro o bode da sala”. Making people aware of the situation is the first step towards a change. The second step is to create a sense of ownership of the public space. Connections from public facilities towards the river are taken into account, embedding the linear connection in the surrounding urban tissue. In this way segments of the valley are linked to public program surrounding it. Schools could profit from playgrounds along the river, hospitals and elderly housing will find a pleasant outdoor space nearby. In this way the local population will feel connected to the scarce public space and the value will be recognised by all, avoiding the risk of illegal occupation. In the actual transformation of the areas that are occupied with buildings the third strategy is applied. The aim is to turn the buildings with their front towards the river. The program that can remain in this zone should be flood-proof and all terrains should be laid out with soft permeable surface. The implementation of a water collector that follows the linear path of the river can stop the pollution of the river and eventually turn the area along the stream into a sequence of strong public spaces. “Tiraro o bode da sala”. Making people aware of the situation is the first step towards a change. The second step is to create a sense of ownership of the public space. Connections from public facilities towards the river are taken into account, embedding the linear connection in the surrounding urban tissue.

- 21. Studio São Paulo 21 Connect the different sections like a necklace

- 22. Studio São Paulo 22 Being in Sao Paulo what strikes me the most is to witness how Paulistanos have begun to succeed in developing an intense, positive energy for their city within a quite short time frame. Ten years after my first visit to Sao Paulo, the mood and atmosphere seem to be completely geared up, something I didn’t expect to see so radically or so soon. There is optimism and openness in this city and a clear will to act and change. To give just one example, the impressive scale and quality jump in public resources is for me one of the most relevant signs of the city’s latest developments and endeavours. It is clearly visible – the breaking down of traffic congestion is something all Paulistanos will be thankful for, but above all it improves social integration and accessibility for everybody. Nevertheless, the change I have witnessed with the biggest impact has been twofold. Firstly the shift in attitude by the Municipality towards the reality of the poorer neighbourhoods, and secondly the acceptance of uneasy realities as a starting point for improvement guided by a strong participatory processes. Reality as a starting point sounds quite obvious, but it is not. It is often ignored because it takes time needs political Moving in the right direction by Gert Urhahn courage to overcome. Take Amsterdam for instance, the city where I live and work as urban designer. In 1973, the municipality of Amsterdam had drawn up demolition lists for entire neighbourhoods based upon the research of the Town Planning Department, the Department for Social Housing and the Building Department. At the time the typical working mode was based on separation with little cooperation between departments. Yet the general idea among these experts was to knock down most of the 19th century labour housing districts –considered obsolete and inappropriate. In its place they would have built brand new housing blocks as they were already doing in the new extended areas of the city, designed according to the modernistic philosophy and planning standards of the time. As soon as the first of the old quarters had been broken down, students and entrepreneurs began a strong resistance. Eventually only one man - Jan Schaefer, the alderman of the Municipality- stood against the extensive demolitions: he dared to say NO. Perhaps more surprisingly, he was able to turn the perfectly organized machine for redevelopment in a different direction. Before starting as politician, he was a

- 23. Studio São Paulo 23 baker in one of the areas planned for redevelopment. He understood, as few other people did, what kind of ravage it meant for the local residents and business people of these communities. He had the experience, the power and the will to change, and the audacity to do it. Nowadays, most of those areas are the best beloved places to live and work in the city. Looking back I am surprised that this happened in a city like Amsterdam and so recently as well. Now it seems to me like a bad dream that ended happily, and I see a similar a transition moment for Sao Paulo too. Parallel to the acceptance of reality as such and the wish to operate within it, I recognized the wake of another remarkable turn: the positive tendency to start thinking not only of city extensions but towards transformation of the existing urban fabric. Sao Paulo is a fast growing metropolis. After a period of never ending extensions, the need and consciousness for transformation of the existing fabric is rising. It concerns at the same time the consolidated centre and new sub-centres, as well as favelas and the industrial areas that have been metabolized by the city. Transformation of these existing structures is by definition more complex, but as a counterpart is more urban, more differentiated and dense. Lastly but by no means least the city becomes more deeply sustainable - socially, economically, and with regards to infrastructure. The right direction is already very present in the paulistan planning departments, though the move from extension to transformation is not instrumentally ripe yet. The potential to critically reverse the balance lies under the burden of bureaucratic and technocratic constraints. These constraints are only strengthened by time pressures to complete what are often complex yet urgent demands. Such required shifts imply other ways of operating; not only dealing with people -inhabitants and entrepreneurs but also the existing physical and social structures. Above all however it requires a more inter- disciplinary approach. Little by little the situation can be freed up for reflection. I feel this closely as it is not so very long ago that similar changes were needed that provoked a radical turn to a new set of priorities also in Amsterdam. “Before starting as politician, Jan Schaeffer was a baker in one of the areas planned for redevelopment. He understood, as few other people did, what kind of ravage it meant for the local residents and business people of these communities.”

- 24. Studio São Paulo 24 Through the debate of concrete problems in the city of São Paulo, Studio São Paulo made it possible not only to come up with richer solutions by combining different points of view. The collaborative design and debat also led to the understanding of the differences of urban planning and public policies in both countries. A focus on the project is one of the main Brazilian obstacles, where the legislation treats in a general way and without a specific plan for the real problematic situations presented in each locality. There is an abysm between the legislation and the project, which provokes a difficult relationship leading to many barriers towards realisation. It makes evident that there is a lack of planning with public participation in order to establish a healthy relationship between legislation, planning and project, and a lack of project reflecting the needs of the local population. Long term planning and the discussion about public participation were pointed out as two of the most prevalent difficulties of elaborating projects with greater dynamism in Holland. On the other hand, the closer relation between project and plan allows a greater dynamic in the improvement of the laws concerning public space. As a consequence, the projects have less legal obstacles, allowing for greater agility in the public discussion and therefore better representing the needs of the population. Case Study The lower valley, is a problem treated in a generic way by the municipal planning office, without the specification of the diverse difficulties of each locality and the relation with its surroundings. We noticed that the richness of the characteristics of our studied site allows the city to return the water and to its inhabitants, providing the relation with a healthy public place for its local population and not only a crossing point. The plan gives trust to, and requires responsibility of, the local residents and users, This way public participation becomes concrete andhelps to answer each section of the valley with a specific and pracmatic solution. The project is a wonderful example of how São Paulo’s lower valleys can be tranformed to valueable places in the city putting the local place and place central. Making cities for people by Ricardo Correa

- 25. Studio São Paulo 25 Sao Paulo is the roaring engine of a booming country. At the same time the cars in the streets of Sao Paulo don’t get a lot of chances to roar, especially during rush hour. Sao Paulo traffic is as sticky as the local chocolate speciality: the brigadeiro. Our hostel was not so far from the Studio Sao Paulo workshop at the Martinelli building in the center and we also had the choice between taxi and metro. So we were blessed in two ways: we slept nearby and we could avoid the road. As many Paulistans are stuck choosing between their car and the (relatively well organized) bus system, which both have to stand in the same bee line. As Dutch natives, we wondered what the city would be like with bikes instead of cars. That Sunday we got served already. The Brazilian office TC Urbes is a pioneer at the front of urban cycling and took us for a ride. Because the workers stay at home or escape the city, the streets are freed from traffic. Main roads are partially closed off to created temporary dedicated bike lanes. Getting on however, meant not being able to get off for some time. Those lanes were located at the middle of the road, locked between the remaining cars. A claustrophobic experience for the Dutch cyclist. This seems to be typical, as the few Sticky as a Brigadeiro By Kria Djoyoadhiningrat permanent bike paths resemble highways, instead of the small scale bike paths we’re used to. Where the Dutch system has small scale, bottom up properties, the Brazilians started thinking upside down. Going along one of the nicer bike highways along the river Pinheiros an intense odour filled our lungs. We were unpleasantly surprised. Why would anyone build such a nice bike path along such a foul place? We would certainly first have cleaned the place out before exposing anyone to this environmental disaster. Did they make a mistake here? During the workshop we were making the plans for the linear parks, that always follow a river or stream. We found out that this upside down planning may not always be intentional, it has a unique positive side effect. A sublime motivation to action is triggered by the exposure to the evident open quality of the river and the foul smell at the same time. Many of the visitors of the park and cyclists and runners using the bike path rallied local politicians to address the various sources of pollution around the city. Cleaning is becoming an undeniable item on the agenda. Hopefully the traffic will soon stop being as sticky as a brigadeiro, and Paulistans will only eat brigadeiros to fuel their human powered vehicles. Going along one of the nicer bike highways along the river Pinheiros an intense odour filled our lungs. We were unpleasantly surprised. Why would anyone build such a nice bike path along such a foul place?

- 26. Studio São Paulo 26 Ordem e progresso, it says on the Brazilian flag. Order and progress. Brazil is a proud democracy, where progress is defined not only in technical development and economic growth. It is clear that real progress would be to fulfil the dream of an egalitarian society. The fulfilment still faces big challenges both in racial terms, and in ownership terms. It is exciting to see the political imperative in much of the planning. Planning is an instrument to create this equality, which is one of the reasons so much is invested in low-income housing. Shaping the living environment of the city is the major focus of the social agenda of politicians. The reason for this focus on housing is a logical one. It is in the house, and in the regeneration of the street, that progress becomes palpable. The house and the street form the community, and the community elects the politician. That is the second reason that it is so exciting to work within this democratic political context. In Brazil, it is the relationship between the politician and his or her constituency (and not the relationship with Goldman Sachs, as, one might say, in the rest of the world) that drive projects and programs. Politicians are ‘of the people’, povao. Lula, the previous president, a prime example, based his mandate exactly on his promise to strive for equality. So does the current president, Roussef. And on a smaller scale, as we saw in Heliopolis, it was the local MP who was the driving force behind the housing and slum clearance projects. We were excited to discover again the power of this democratic imperative. We talked to candidates for political office who wanted us to help them with a planning strategy. We were happy to see that when we discussed the political dimension of other long term planning interventions, such as the need for inclusiveness in the downtown area, these were met with approval. It was striking, however, and that is the trap of this politically motivated planning, that long term planning issues where not foremost in the mind of the politicians we met. Projects needed to be concrete, involve the local community, and focus on housing. The four year span of elections was dominant in their thinking. How, we asked ourselves, can concrete and manageable projects be combined with long term perspectives? Two cases COHAB/SEHAB is the secretary of housing and has defined a strategy of creating social housing in some of the many empty buildings in the centre to draw new inhabitants into this underoccupied part of the city. At this moment the city centre is not an inclusive city where people live in, work in and visit, it is only a CBD. The context of the projectcase is that the centre needs to position itself in a city that is becoming poly- Ordem e progresso by One Architecture & POSAD Brazil’s bureaucracy, as we have discovered in the Martinelli building, likes to keep things manageable.

- 27. Studio São Paulo 27 centric. It should generate the investment of social and financial capital in the centre. Within the case we stated that it is not about filling the buildings, quantitatively hardly effective in relation to the scale of the centre, but about place making. By focussing on core-areas in the centre the COHAB/ SEHAB initiative becomes part of a strategy to build- up inner- city identity. These areas need (besides residents) parking, safety, links to public transport and a local street management. With smaller defined urban generation projects we can focus on city areas instead of buildings. For the other case, the Linear Park, the secretary of green space and environment was the main driver and client. They have to deal with a number of problems. Their first problem is that the infrastructure of Sao Paulo is built over or on top of the rivers in the city. This means that in case of flooding the traffic is completely dysfunctional. The second problem is that the hair veins of the water system are clogged by pieces of city, like cholesterol and fat in an obese person. Illegal housing is built on, in and over the riverbeds. This illegal city pollutes the river from the source on. Third is the lack of green spaces in the city that can help to cool the urban fabric, but also as a green space for people. We noticed that the Secretario's strategy to transform some of the clogged up waterways into linear parks is very difficult to execute. They are planned as a masterplan but not phased in such a way. The created public spaces lack meaning or users and get either undesirably fenced or vandalized. Instead, the focus should be on the linear and not on the parks, making networks. The neighbourhoods should be connected in a better way to adopt a part of it as their backyard. Ownership should be created. This helps creating a planning logic that is phased in a lot of interconnected sections. The surrounding city adopts and creates these sections. The network combines it. Progress: Integrate long term vision in political vocabulary Following Auguste Comte, the positivist philosopher who was responsible for the slogan on the flag, progress needs order. Next to the democratic imperative stands a well- organized, too organized, bureaucracy. Brazil’s bureaucracy, as we have discovered in the Martinelli building, likes to keep things manageable. It needs to, because of the bureaucratic complexity and because of the political demands for concrete results within the term. And maybe it wants to, to be honest, for opportunities for fast and easy results. This reduction of scope, complexity and timescale results, as it does anywhere, in suboptimal project definitions. Opportunity reigns supreme. How, we asked ourselves, can concrete and manageable projects be combined with long term perspectives?

- 28. Studio São Paulo 28 be integrated in political terms and in political vocabulary. This way the long term and the big scale can be safeguarded by a Secretario. Most of the goals set are very one-dimensional, and by overlooking the connecting issues the cure can be worse than the disease. In the case of the Linear Parks for example, when solving the water problem one should be aware of building strong networks instead of unused, fenced ‘public space’. Likewise, in the case of the inner-city, bringing and maintaining life to the city requires complementary and necessary centre facilities. And in the case of the Petrobras, when building social housing for favela’s one should be aware of not destroying future green places that form the last gold (or breathing space) of the city. Order: Integral needs local The scale at which Sao Paulo is developing is nothing less than awesome. The city has, as has been shown earlier, done 200 years in 70. And the end of development is not in sight, not demographically, but also socially, culturally and economically. With the biggest mineral reserves in the The housing program for Centro of SEHAB/ COHAB, the introduction of more than 2000 new units in ‘underused’ properties, was not linked to the development of the area as a whole. The linear parks in the east were not related to the urban development around them. The slum clearance and planned housing near Heliopolis of SEHAB/ COHAB was not linked to transit- and green development by the urbanism and green departments. Progress is accommodated by order, we found, but also hindered. The ‘Plano Director’ is an example of a plan that lacks a clear vision on ‘progresso’ but mainly consists of ‘ordem’: the recording of a series of separate projects. There is a gap between the large scale level of the governance in Sao Paulo and the short term of the vision making. The scale is massive: the whole German Sheppard (like the Paulistans use to refer to the shape of the municipal boundary on the map, resembling the head of a dog) is their territory, but the short timeframe of a political four years is the basis for most visions. The secretaries have to deal with a layer cake of integrated problems (like water and infrastructure and green) and these problems have to be treated in a quick and dirty, hands- on manner that fits in four years of politics. The logical result is a planning policy based on opportunism. We feel that the long term vision should Most of the goals set are very one-dimensional, and by overlooking the connecting issues the cure can be worse than the disease.

- 29. Studio São Paulo 29 world, including the offshore oil, and the true ambition to let the entire (growing) population actively participate in the country, Brazil just might be the richest country in the world in the (not so far) future. This will mean that Sao Paulo will not just double, but grow by a factor 10 in terms of Gross Regional Product. Already the investment programs are massive but, as can be seen in the graph, mostly focused on the ‘four year projects’, dominated by housing. The real question for Studio Sao Paulo, therefore, is how local, opportunistic and short term projects can be thought such that they will contribute to the long term planning goals for the city? And, maybe before that, how can we help translate the democratic goals strategically into long term planning goals, into more than just the availability and accessibility of housing? There is a chance to use that opportunism, that fast metabolism of the city and to connect it not only to a larger agenda but also to connect it to local stakeholders. Opportunistic driven projects can be carried out by a local organ like a neighbourhood, a school or a church community. The people in Sao Paulo can take responsibility to shape their own living environment. In the example of the Linear parks we show that this helps to form better networks and also to create ownership; feeling responsibility and ‘at home’ in public space. To ensure public space can perform better, it are not the safety issues that matter most but the connection of a local heart to it. In the case of the inner-city local entrepreneurs, inhabitants and cultural institutions make or break city life. Some is guidable top down by regulation or for instance creation of parking facilities, but most is powered locally and needs local governance. Operate on an intermediate scale level Brazil knows, like in the Netherlands, different authorities on different levels. All have their separate responsibilities. We believe that Sao Paulo should operate on an intermediate scale. The large scale is not an executable. It is the scale of directing the market and organising structures and networks. On the scale of making projects the city is king; it can move fast and steady. This intermediate scale could help to organise the more local parties to be the ‘client’, the government restricts to the networks and the market helps to facilitate the making of it, only if the ‘client’ accepts a sort of ownership. Large scale, short term and making projects can become very closely related. Hereby skipping the ownership and integrality of the built projects. The use and development of the public realm can take shape by introducing the intermediate scale, local integration of opportunism driven projects and a guiding government. We believe that Sao Paulo should operate on an intermediate scale. The large scale is not an executable. It is the scale of directing the market and organising structures and networks.

- 30. Studio São Paulo 30 São Paulo is complete in every spot, even though sometimes left out. At least for me as a stranger, born in Suriname, raised in the western Netherlands. I will illustrate this completeness, and in the same time ‘forgottenness’, by the crossing of avenida São João with vale do Anhagabaú, a central spot in the historical city center of São Paulo, where the old and new town, Sé and República are separated. A place that did something to my heart maybe in the way Caetano Veloso was moved by the crossing a little further on avenida São João, crossing Ipiranga. A place where I maybe look unto like ‘the giant stranger’ from the twins, overlooking the valley from my working spot, on top of the Martinelli building. I perceive the movement from above, the way I believe most Paulistans do. A little anxious I take the elevator to the ground level. Stepping out of the Martinelli building, looking from behind the trees, seeing first the police, standing next to their truck, facing me. Facing only this side, the side where most of the offices are in function. The side with filled buildings all day, until the afternoon, maybe 5-, 6- or 7pm. The time after which every street, building and corner becomes empty, abandoned, like the rest of the old (Sé) en even the new town (República). But aside from that, it’s around noon now, when I cross the valley of Angabaú. The valley is empty already, like an urban void, even though planned, designed and built. Behind the police truck there is a little valley, better called a lower square, a place people have to walk around, which forms a barrier in the street. Something that stops most Paulistans from taking this route. São Paulo complete, sometimes forgotten. by Heidi Klein In the song ‘Sampa’ Caetano Veloso sings that something happens in his heart only when it crosses Ipiranga and avenida São João. ‘The stranger’, ‘O estrangeiro’, was a street art project between SESC, Prefeitura de São Paulo, Plasticien Volant and Os Gêmeos, realized in 2009 for the ‘year of France in Brazil’. It was recently painted over, 30 days before demolishing of the building it was painted on.

- 31. Studio São Paulo 31 Behind the lower square, across from the beautiful monumental ‘Prédio do Correio’, a spot that the stranger cannot over look, a place that the police is not facing. There are the girls, soliciting. Just in front of ‘Bom Pastor’, the evangelical bookshop, in the mouth of avenida São João. Across the street, across from the girls, next to the ‘Prédio do Correio’ I change my money in a lanchonete, to buy some handmade earrings in the center of avenida São João. Every day before noon travelers from Peru, Colombia and elsewhere spread their cloth to sell handcrafts, made from forest seeds, pits from acai, and other natural materials. The lanchonete is regularly busy, selling ‘sucos, pão do queso and coxinha de frango’, while the lady at the magazine kiosk sells the daily news and some homeless simply wander around. This is the part of avenida São João were Google street view leaves you behind. Where the cars and busses have already bent away. It is still tranquil, even though it is lunch time. Some buildings are empty, also during daytime. Even though it is just across from galleria do Rock, and not too far from the Martinelli building. Maybe not in a big amount, but all comes together in that little corner, or actually quite big corner: the crossing of avenida São João with vale do Anhagabaú, with on one site the police, on the other side the girls, the eating and drinking, the handcrafts and all, with the disconnection in the middle, in the shape of a little valley, or better called lower square. Like I said São Paulo is complete in every spot, even though sometimes left out, or better said disconnected. I went away, just like ‘the stranger’ did, maybe back to France. His building will be demolished within this month, to make place for something new, a bit more classy, cultural maybe. One day this left out piece, the crossing of avenida São João with vale do Anhagabaú, will be reconnecting the city parts, the old and new town, Sé and República, in the way that viaduto do Chá already does.

- 32. N d t. o s- s- nt n PROPOSED INTERVENTIONS 01 Promoting interventions in large lots in order to create conditions for local neighborhood units, by encouraging mixed use, associated with the provision of open spaces connected to pedestrian lanes. Those interventions have the potential of recovering the industrial architectural heritage and of generating large-scale social housing, as well as for the real estate market. 02 Encouraging old buildings remodeling; existing structures retrofit; creating new network of pedestrian connections with visual permeabil- ity - those actions shall generate alternative uses at the ground floor of the buildings and the use of the internal areas of the blocks, which provide effective strategies to take advantage of the great number of vacant buildings in the downtown area. 03 Creating situations that increase housing density in these areas, increasing the number of public spaces, areas for services and trade at the lower floors and visual permeability of pedestrian mobility; creating points of implementation in non-motorized transport in order to recon- nect the social relationship of formerly separate districts by the road system interventions. RESULTS The result of those interventions shall possibly start the redevelopment of the downtown area. Not as an isolated intervention, but committed with other public policies for renewal, as the offer of employment for income increasing, mobility improvement, qualification of water re- sources and infrastructure, among others. The interventions focused in housing, however, must content and integrate all the other prospects for renewal, proposing: • People occupation and buidings renovation in downtown Sao Paulo, with the proposition of, at least, 30 000 new housing units, whether social housing or real estate market. • Creation of more economical opportunities for 100,000 people in the region • Rehabilitation of public open spaces • Improvement of the mobility system for public transport and non-mo- torized vehicles schools central area health & care social housing areas subway public spaces urban train highways & aveneus bus stations railroad districts 0102 03 03 HIGHWAY SYSTEM Studio São Paulo 32 We aim to demonstrate the key issues about the transformation of São Paulo central region, with the comprehension of the urban relations that led to its degradation and of the opportunities for intervention generated by this decline. The proposal is shown in a diagram of sequent events, seeking to clarify the generation of opportunities within the central territory and the respective required interventions. The goal is to recover this important and dense area of the city, with regard to people resettlement and to the most effective use of the existing infrastructure, through a system of interconnected interventions. Dealing with the central area recovery as a strategy of creating a place that people want to live in, work in and visit. The territorial limits of the central region in study considers the 12 main districts of São Paulo city center, surrounding Republica and Sé districts which are in the geographical center of this region. Urban relationship in transformation 01 The change of uses generated the abandonment of the industrial activities and the neglect of the high potential land system already consolidated. 02 The economic centrality of this territory shifted towards other regions resulted in the discontinuation of investment in maintenance and infrastructure expansion, which were mandatory to urban development. 03 The build-up of sequent road system interventions during the second half of the 20th century, regardless the contemporary approach to this system and the lack of alternatives of land use, exhausted the possibilities of expansion and renovation of the area, causing its decline. São Paulo’s downtown re-occupation by Renata Semin, José Armênio de Brito Cruz, Rafael Costa, Marlon Longo, Gustavo Partezani and Ingrid Ori (Piratininga Arquitetos ) The goal should be to recover the center as a place that people want to live in, work in and visit. DOWNTOWN RE-OCCUPATION to demonstrate the key issues about the transformation entral region, with the comprehension of the urban rela- its degradation and of the opportunities of intervention is decline. posal is shown in a diagram of sequent events, seeking eneration of opportunities within the central territory and equired interventions. The goal is to recover this impor- area of the city, with regard to people resettlement and to ve use of the existing infrastructure, through a system of interventions. Dealing with the central area recovery as eating a place where people want to live, work and visit. mits of the central region in study considers the 12 main Paulo city center, surrounding Republica and Sé districts e geographical center of this region. URBAN RELATIONSHIP IN TRANSFORMATION 01 The change of uses generated the abandonment of the industrial activities and the neglect of the high potential land system already consolidated. 02 The economic centrality of this territory shifted towards other re- gions resulted in the discontinuation of investment in maintenance and infrastructure expansion, which were mandatory to urban development. 03 The build-up of sequent road system interventions during the sec- ond half of the XX century, regardless the contemporary approach to this system and the lack of alternatives of land use, exhausted the pos- sibilities of expansion and renovation of the area, causing its decline. GENERATION OF OPPORTUNITIES 01The industrial activity was designed with large lots and extensive road system that are nowadays underused due to the shift of the indus- trial activities and some services. 02 The low investment in maintenance and expansion of urban infra- structure in this region resulted in a large vacant group of buildings and sites, either of residential or commercial use, due to the movement towards new centers created in the city. 03 The border lots, overlapped by the highway system, became urban scars and were depreciated as real estate assets due to the urban fabric disruption. ARQUITETOS ASSOCIADOS up: José Armênio de Brito Cruz, Rafael Costa, Marlon ata Semin. uction: Gustavo Partezani, Rafael Costa and Ingrid Ori schools central area health & care social housing areas subway public spaces urban train highways & aveneus bus stations railroad districts 02 03 STRIAL 02 OLD CENTER 03 HIGHWAY SYSTEM SÃO PAULO DOWNTOWN RE-OCCUPATION We aim to demonstrate the key issues about the transformation of São Paulo central region, with the comprehension of the urban rela- tions that led to its degradation and of the opportunities of intervention generated by this decline. The proposal is shown in a diagram of sequent events, seeking to clarify the generation of opportunities within the central territory and the respective required interventions. The goal is to recover this impor- tant and dense area of the city, with regard to people resettlement and to the most effective use of the existing infrastructure, through a system of interconnected interventions. Dealing with the central area recovery as a strategy of creating a place where people want to live, work and visit. The territorial limits of the central region in study considers the 12 main districts of São Paulo city center, surrounding Republica and Sé districts which are in the geographical center of this region. URBAN RELATIONSHIP IN TRANSFORMATION 01 The change of uses generated the abandonment of the industrial activities and the neglect of the high potential land system already consolidated. 02 The economic centrality of this territory shifted towards other re- gions resulted in the discontinuation of investment in maintenance and infrastructure expansion, which were mandatory to urban development. 03 The build-up of sequent road system interventions during the sec- ond half of the XX century, regardless the contemporary approach to this system and the lack of alternatives of land use, exhausted the pos- sibilities of expansion and renovation of the area, causing its decline. GENERATION OF OPPORTUNITIES 01The industrial activity was designed with large lots and extensive road system that are nowadays underused due to the shift of the indus- trial activities and some services. 02 The low investment in maintenance and expansion of urban infra- structure in this region resulted in a large vacant group of buildings and sites, either of residential or commercial use, due to the movement towards new centers created in the city. 03 The border lots, overlapped by the highway system, became urban scars and were depreciated as real estate assets due to the urban fabric disruption. PIRATINNGA ARQUITETOS ASSOCIADOS January, 2012 Workshop group: José Armênio de Brito Cruz, Rafael Costa, Marlon Longo and Renata Semin. Text and production: Gustavo Partezani, Rafael Costa and Ingrid Ori schools health & care subway urban train bus stations 01 INDUSTRIAL 02 OLD CENTER 03 HIGHWAY SYSTEM

- 33. Studio São Paulo 33 Generation of opportunities 01The industrial activity was designed with large lots and extensive road system that are nowadays underused due to the shift of the industrial activities and some services. 02 The low investment in maintenance and expansion of urban infrastructure in this region resulted in a large vacant group of buildings and sites, either of residential or commercial use, due to the movement towards new centers created in the city. 03 The border lots, overlapped by the highway system, became urban scars and were depreciated as real estate assets due to the urban fabric disruption. Proposed interventions 01 Promoting interventions in large lots in order to create conditions for local neighbourhood units, by encouraging mixed use, associated with the provision of open spaces connected to pedestrian lanes. Those interventions have the potential of recovering the industrial architectural heritage and of generating large-scale social housing, as well as for the real estate market. 02 Encouraging old buildings remodelling; existing structures retrofit; creating new network of pedestrian connections with visual permeability - those actions shall generate alternative uses at the ground floor of the buildings and the use of the internal areas of the blocks, which provide effective strategies to take advantage of the great number of vacant buildings in the downtown area. 03 Creating situations that increase housing density in these areas, increasing the number of public spaces, areas for services and trade at the lower floors and visual permeability of pedestrian mobility; creating points of implementation in non-motorized transport in order to reconnect the social relationship of formerly separate districts by the road system interventions. Results The result of those interventions shall possibly start the redevelopment of the downtown area. Not as an isolated intervention, but committed with other public policies for renewal, as the offer of employment for income increasing, mobility improvement, qualification of water resources and infrastructure, among others. The interventions focused in housing, however, must contain and integrate all the other prospects for renewal, proposing: • People occupation and buildings renovation in downtown Sao Paulo, with the proposition of, at least, 30 000 new housing units, whether social housing or real estate market. • Creation of more economical opportunitiies for 100,000 people in the region • Rehabilitation of public open spaces • Improvement of the mobility system for public transport and non-motorized vehicles • Improvement of the urban landscape

- 34. Studio São Paulo 34 and here I begin I spin here the beguine I respin and begin to release and realize life begins not arrives at the end of a trip which is why I begin to respin [...] Haroldo de Campos, Galaxias 1984, and here I begin A fast growing metropolis as Sao Paulo is hardly graspable, it is impossible to get under total control. That is its raison d’être, what makes it alive and vibrant by getting written and rewritten every day by its planners, its architects, the municipality, its citizens, its visitors. Acknowledging that not everything can -and has to- be under control, is not a defeat: it is an objective strategy to deal with the actual complexity and break it down in time and place in order to handle it. Not all questions can be answered at the same time, but they should be looked at in an integral way, with open and long term visions, and a clear hierarchy of which are the real public values, at neighborhood as well as at city scale. Public value is a sustainable answer to urban pressure, it is what is important for us all on long term, and is specific to each context and scale. After many decades of expansion and growth, the city of Sao Paulo is changing attitude and tries to consolidate within its boundaries. Besides all the positive aspects of this, the only disadvantageous consequence is that urban pressure is threatening all remaining vacant spaces establishing no solution of continuity in the city. Urban vacancies -especially in the case of Sao Paulo- are an asset to let public value increase and develop. One of the keys to fullfill growing pressure and consolidate the city without forcedly exploiting all remaining available land, is working with density within the already built fabric. An important detail of this is On public value: towards a coherent and more livable São Paulo by Bernardina Borra, Gert Urhahn, Luis Pompeo and Tiago Oakley

- 35. Studio São Paulo 35 that Sao Paulo has the capacity to increase its density within its inner structure, and also to reach a balance between urban open spaces and building matter, cause people are craving not only for houses and facilities, but for lively and safe collective spaces, parks, and streets as well. The spatial conditions that can endorse public value to unfold in Sao Paulo, are quite different from what is happening in many western cities, and demand for a specific approach. It has to take into consideration long-term and more complex and integrated urban strategies, looking for continous flexibility to change in time. On the one hand the meaning of Paulistan public values should be set under local culture understanding, and how this two can take place for the benefit of the many, co-existing and collaborating between municipality, private owners and individuals mindset. However, on the other hand, in order to create them, some basic frameworks could be set to tackle the complex specificity of Sao Paulo’s metropolis: scale switch, open developments and typologies, cooperation and radical user-oriented procedures. Scale switch Zooming in and alternately zooming out, so to say switching scale –desing and thinking wise-, means embracing a development process simultaneously at the disposal of many initiators in various locations and densify locally and regionally the metropolitan context, including neighbour cities in every sense. In Sao Paulo the three scales of neighbourhood, meso and regional are of crucial importance to mediate the Metropolis vastness. It is essential to map out local needs, relevant players in renovation districts and the prospects — or rather obstructions — they face. A thorough examination of both social conditions and urban context is a necessary strategy for the urban planner and this demands a sharp eye for detail. Open developments and typologies Density in building, urban functions, and lifestyle are constantly changing factors, especially in a fast growing economy like the Paulistan one. That means that a city district or quarter must be able to adapt according to changes. The non-linear design of a city ensures its vitality. Simultaneous Zooming in and alternately zooming out, so to say switching scale, means embracing a development process simultaneously at the disposal of many initiators in various locations.

- 36. Studio São Paulo 36 supervision of project initiators, in varying frequencies and directions, is of paramount importance, it must be absolutely get constantly tuned with the map indicating a wide range of possibilities and specific opportunities that come along with time speed. To benefit from those changes is important for informal settlements as well as for established ones, making room for organic growth, sustainability and collective acceptance. Specifically facing roaring growth and urgent problematics two different kind of typolgical approach can play a crucial support in open developments in Sao Palo. On the one hand high speed housing and industrial sector in Sao Paulo is the starting point and require specific fast and affordable construction technics, suitable for different contexts within different fabric. Namely prefab, cascos, light urbanisme could be among the most used solutions for building typologies. On the other –even previous to building ones- urban fabric typologies can act as an urban methodology to distill a grammar of the composition of different parts of the city. The latter one investigates qualities of existing urban fabric and indicates the qualitative integration of built an open space, indicating as well the possibility for which bulding typologies are most suitable locally. By building into a consolidated urban fabric, you’re already building in the city in a seamless system. If actual laws might make it more difficult, especially to implement mixed use buildings, merging public and private use, such as a housing block with a school in the ground floor, this should perhaphs be reconsidered within the open process development. In the end open development for densification strategies has not only pure social and spatial public value improvements, but consequently it also generates real estate value of the land and its surroundings. Cooperation and user oriented Defining and shared ambitions is a political and practically efficient integration process at all levels – between different municipalities, within municipality departments themselves, and between all local stake holders- that must be developed both publicly and expertly. It involves collective investment, for example in innovative energy infrastructure or water quality, in order to conserve a city’s heritage and ultimately it enhance its public values. Acknowledgement of separate entities and future values is a component of a producer’s anticipatory and imaginative power. Nature, water, landscape, accessibility, heritage, architecture and all peculiar features of Sao Paulo might combine to create public values and inspire new forms of utilisation. In anticipation of this future vision, the planner works on developing an area’s quality, unique character and coherence, confident of the city user’s resilience and conflict-resolving nature. This can be either latent or new potentials, up to the urban planner to find them out with the help of the participants involved. By building into a consolidated urban fabric, you’re already building in the city in a seamless system.

- 37. Studio São Paulo 37 Indeed in order to create public concern and social responsibility to foster public life –and safety for it- , participatory structures must surpass participation itself, and achieve social reliability. Sao Paulo is already far ahead in citizens’ participation than many other countries. Their energy, creativity and investment capacity is bred and consciously considered, conscious that an individual owner will not succeed on his own upgrading a certain area, but collective efforts of several neighbours well orchestrated can become critically effective and structurally help changing. Maybe other levels can be added on top of the existing partcipatory procedures, not only micro-financing or civic economy solutions, but plenty of innovations can already be among the people in place, from top businesses through to deprived urban districts. Long term planning could help going deeper in the positive groove set years ago by the Estatudo da Cuidade. It could release official zoning and land use laws, favouring a more flexible control, could be one of the msot crucial factors to involve active participation. A more radical participation is in the genealogy of history and develoment of Brazilian citizenship, and the integration of human experiences in transforming their own neigbourhoods, is common acting. Residents, associations, companies and co-operatives should be given an active role in urban renewal initiatives. Boosting of endogenous investment capacity plays a central role for integrated processes to foster public value.