2013 FDA Audit Finds Major Issues in Canada's Electoral System

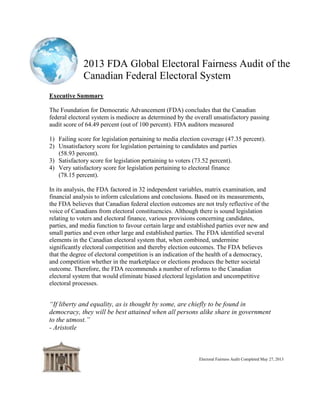

- 1. 2013 FDA Global Electoral Fairness Audit of the Canadian Federal Electoral System Electoral Fairness Audit Completed May 27, 2013 Revised Recommendations on May 28, 2013 Executive Summary The Foundation for Democratic Advancement (FDA) concludes that the Canadian federal electoral system is mediocre as determined by the overall unsatisfactory passing audit score of 64.49 percent (out of 100 percent). FDA auditors measured 1) Failing score for legislation pertaining to media election coverage (47.35 percent). 2) Unsatisfactory score for legislation pertaining to candidates and parties (58.93 percent). 3) Satisfactory score for legislation pertaining to voters (73.52 percent). 4) Very satisfactory score for legislation pertaining to electoral finance (78.15 percent). In its analysis, the FDA factored in 32 independent variables, matrix examination, and financial analysis to inform calculations and conclusions. Based on its measurements, the FDA believes that Canadian federal election outcomes are not truly reflective of the voice of Canadians from electoral constituencies. Although there is sound legislation relating to voters and electoral finance, various provisions concerning candidates, parties, and media function to favour certain large and established parties over new and small parties and even other large and established parties. The FDA identified several elements in the Canadian electoral system that, when combined, undermine significantly electoral competition and thereby election outcomes. The FDA believes that the degree of electoral competition is an indication of the health of a democracy, and competition whether in the marketplace or elections produces the better societal outcome. Therefore, the FDA recommends a number of reforms to the Canadian electoral system that would eliminate biased electoral legislation and uncompetitive electoral processes. “If liberty and equality, as is thought by some, are chiefly to be found in democracy, they will be best attained when all persons alike share in government to the utmost.” - Aristotle

- 2. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 2 of 82 Prepared By Mr. Stephen Garvey, Executive Director Foundation for Democratic Advancement, Bachelor of Arts in Political Science, University of British Columbia and Master of Philosophy in Environment and Development, University of Cambridge. Peer Review By Mr. Nick Brown, Diploma Public Relations, University of London, Diploma Internet & Multimedia Information Systems, South Bank University, Bachelor of Science, University of London, and Masters of Science, Geography, Kingston University; Mr. Steve Finley, Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering, Purdue University, Master of Business Administration, Indiana University, and Juris Doctor, Valparaiso University; Ms. Lindsay Tetlock, Bachelor of Arts in International Relations and Master of Arts in Historical Studies, University of Calgary. Purpose of the Canadian Electoral Fairness Audit The purpose of the Foundation for Democratic Advancement (FDA)‘s electoral fairness audit (the ―Audit‖) is to determine a comprehensive grade for Canadian federal electoral fairness. In addition, the FDA seeks to further establish benchmarks for electoral fairness, identify areas of democratic advancement and progression, and encourage democracy reform where needed. The goal of the FDA's Canadian electoral fairness report is to give the people of Canada and other stakeholders an informed, objective, non-partisan perspective of the Canadian federal electoral system and provide recommendations for reform. The views in this electoral fairness audit are the views of the FDA only. The FDA‘s members and volunteers are in no way affiliated with Elections Canada or any of the Canadian registered/non- registered political parties. The Audit is an independent assessment based on objectivity, transparency, and non-partisanship. The FDA assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors in the measurement and calculation of its audit results or inaccuracies in its research of relevant Canadian legislation. About the Foundation for Democratic Advancement The Foundation for Democratic Advancement (FDA) is an international independent, non-partisan democracy organization. The FDA‘s mission is to measure, study, and communicate the impact of government processes on a free and democratic society.

- 3. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 3 of 82 Overall, the FDA works 1. to ensure that people become more knowledgeable about the outcomes of government processes and can then make decisions that are more informed; 2. to get people involved in monitoring government processes at all levels of government and in providing sound, practical, and effective suggestions. (For more information on the FDA visit: www.democracychange.org) To ensure its objectivity and independence, the FDA does not conduct privately paid research. However, if you or your organization has an important research idea or are aware of an important issue on government processes, the FDA is available to listen to your idea or issue and possibly help raise public awareness by initiating and leading change through report research and analysis. Please contact the FDA at (403) 669-8132 or email us at info@democracychange.org for more information. An online version of this report can be found at: www.democracychange.org For further information and/or comments on this report please contact Mr. Stephen Garvey at stephen.garvey@democracychange.org

- 4. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 4 of 82 Table of Contents Introduction 4 How to Read the Report 5 Chapter 1: Electoral Finance Audit Results 8 Analysis 19 Chapter 2: Media Election Coverage Audit Results 21 Analysis 27 Chapter 3: Candidates and Parties Audit Results 28 Analysis 49 Chapter 4: Voters Audit Results 51 Analysis 62 Chapter 5: Overall Audit Results 63 Chapter 6: Analysis 64 Chapter 7: Conclusion & Recommendations 69 References 73 Appendix: Research & Audit Methodologies 78 FDA Research and Audit Teams 84

- 5. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 5 of 82 Introduction The FDA based its audit of Canadian‘s federal electoral legislation on non-partisanship and objectivity. The FDA audit process entails three major components: 1) Research of Canadian's federal electoral legislation and any related legislation and documents. 2) Audit of the legislation based on audit team consensus, the FDA‘s matrices, financial spreadsheets, and scoring scales. 3) Analysis of findings. The FDA bases its matrix scoring scales on the fundamental democratic principles of legislative neutrality, political freedom, and political fairness, and the comparative impact of variables on democracy. For example, if there is no electoral finance transparency it will affect other variables such as legislative process. Without financial transparency, it is near impossible to enforce reasonably electoral finance laws, which prevent and uncover electoral finance wrongdoing. Consequently, according to the FDA‘s matrices, a zero score for financial transparency will result in a zero score for legislative process as well. The FDA‘s research component is purely objective, based on a compilation of legislative information and financial data for the Canadian system and any related findings based in fact and sound empirical research. The FDA‘s audit component is both objective and subjective. It is objective when determining yes and no facts, such as does country ―A‖ have caps on electoral contributions—yes or no? It is subjective because of the predetermined scores for each audit section, and the scores determined for each section. The FDA acknowledges that there is no absolute scoring system or determination of scores. The FDA minimizes subjectivity through its non-partisanship position and by basing scoring on legislative research, financial calculations, and team audit consensus. The FDA scoring scales for each section of the audit derive from consensus of the FDA auditors and survey results of relevant academic and professional persons, and core democratic concepts such as electoral legislative neutrality and political freedom and fairness. Finally, the FDA requires a minimum quorum of five experienced auditors during audit sessions. For further discussion of the FDA methodology, please see the Appendix on page 74. The FDA is a registered non-profit corporation, and therefore it cannot issue tax-deductible receipts. In addition, the FDA is the sole funder of this report. As a policy to maintain its independence and objectivity, the FDA does not conduct privately funded research projects. The FDA relies on donations. If you value this report, please consider donating to the Foundation for Democratic Advancement to help cover the costs of producing this report and communicating its content to the stakeholders, and to continue its work in Alberta, Canada, and abroad.

- 6. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 6 of 82 How to Read the Report Chapters 1 to 4 focus on the four sections of the FDA‘s audit of the Canadian federal electoral system. These chapters are formatted in the following manner 1) Chapter summary and table of audit results for the section. 2) Audit questions, legislative research and audit findings on each audit subsection. 3) Analysis of audit measurements and findings for the section. Chapter 6, ‗Overall Analysis‘, pertains to the measurements and findings from all four audit sections. Definition of Key Terms The Foundation for Democratic Advancement characterized the following definitions Candidates and parties (audit section three) The opportunity and ability of candidates and parties to campaign in the public domain for elected positions. This opportunity and ability occur before, during, and after an election period. Candidates and parties may involve election content of media, electoral finance, and voters (as defined below). In the terms of the FDA electoral fairness audit, which focuses on electoral process, candidates and parties include: 1) Registrations requirements for candidates and parties. 2) Laws on candidates‘ and parties‘ access to media and reasonable opportunity to take advantage of the access. 3) Regulations on access to major debates. 4) Electoral complaints process for candidates and parties In the FDA electoral fairness audit, candidates and parties only encompasses laws, regulations, procedures etc. that affect the influence of candidates and parties. For example, candidates and parties does not encompass laws on electoral complaints by voters nor does it encompass laws on voter assistance at polling booths. Electoral fairness The impartiality and equality of election law before, during, and after an election period. In the context of the audit, electoral fairness involves concepts relating to election content in the media, candidates and parties, electoral finance, and voters. In particular, this includes evaluating impartiality and balance of political content in the media, equitable opportunity and ability for registered candidates and parties to influence voters and government, equitable electoral finance laws, and equitable opportunity and ability for voters to voice political views and/or influence the outcome of an election.

- 7. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 7 of 82 Electoral fairness does not allow bias through, for example, legislation that gives a distinct electoral advantage to one registered party over another, or laws that allow equitable access to media without facilitating equal opportunity to take advantage of this access. In contrast, electoral fairness would include a broad, balanced diffusion of electoral propaganda by registered political parties during the campaign period, equal campaign finances (beyond equal expenditure limits) for all registered parties according to the number of candidates endorsed, and the registration of parties based on reasonable popular support (rather than financial deposit or unreasonable popular support). Electoral fairness in any democratic process must include an equal playing field for registered parties and candidates, distinguishable by voters according to a clear political platform, and a broad and balanced political discourse in where information about electoral choices are clear and available to the voting public. Electoral finance (audit section one) Electoral finance laws applied to registered candidates and parties before, during, and after an election period. Electoral finance also encompasses campaign finance which is restricted to the campaign period. In the context of the FDA electoral fairness audit, electoral finance includes: 1) Caps on electoral contributions (or the lack of). 2) Caps on candidate and party electoral expenditures (or the lack of). 3) Procedures for financial disclosure and reporting of candidate and party electoral finances. 4) Procedures for the handling of electoral contributions by registered candidates and parties. Electoral finance does not include non-financial laws, regulations, procedures etc. such as those relating to candidate and party access to media, civil rights laws such as freedom of speech and assembly, rules on right of reply in the media, laws on the election content of media, and laws on voter assistance. Special interest-based democracy A system in where either individual or corporate interests dictate government action and factions with the most economic and political power in society influence policies and legislation. The electoral system is set up to allow special and minority interests to impact election outcomes primarily through electoral finance and media access and exposure. People-based democracy A system where power is invested in the people and the population as a whole influence government policies and legislation. The electoral system is set up in a fair and equitable manner so that all citizens, within reason, have an opportunity to influence the election outcome to the same degree.

- 8. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 8 of 82 Media election coverage (audit section two) The political content of radio and television broadcasters, the printed press, and their online components during election periods. This content may include news stories, editorials, articles, programs, and group analysis and discussion. It does not include electoral advertisements by candidates, parties, and third parties. Electoral advertisements by candidates and parties are included in candidates and parties, and electoral advertisements by third parties are included in voters and electoral finance. In the context of FDA electoral fairness audit, election coverage of media includes: 1) Registration requirements for television and radio broadcast companies and press companies. 2) Laws on the ownership concentration of media (or the lack of). 3) Laws on the election content of media before, during, and after a campaign period. 4) Laws on freedom of the press and broadcasters. The FDA defines ―balance‖ in the media as having equal political content of all registered political parties presented during the election period. Voters should receive balanced information on all registered candidates and parties in order for election outcomes to reflect the will of the majority. The FDA does not support the idea that incumbent or previously successful parties should be favoured in media coverage in a current election as this could create bias based merely on past results, and potentially weaken the process of capturing the will of the people in the present. In addition, the FDA does not support unlimited freedom of broadcast and press media and believes there is a misleading connection between this and democracy. The purpose of democratic elections is to capture as accurately as possible the will of the people from districts. Broad and balanced electoral discourse creates an informed electorate and supports the will of the people. The FDA concedes that media ownership concentration laws aimed to produce pluralistic ownership could cancel out any imbalance in political content and provide equitable coverage of all registered political parties. Voters (audit section four) The citizens who are eligible to vote and their opportunity to express that vote and a political voice through articles, letters to editors, blogs, advertisements, spoken word etc. in the public domain. Voter influence applies to the period before, during, and after an election. In the context of the FDA electoral fairness audit, which focuses on electoral process, voters include: 1) Laws and regulations on freedom of speech and assembly. 2) Laws on the registration requirements for voters. 3) Laws on voter assistance at the polling booth. 4) Laws on the inclusion of minorities in the electoral process. In the context of the FDA electoral fairness audit, voters may be impacted by the election content of media, and candidates and parties and electoral finance law. For example, no cap on contributions to candidates and parties will affect voters because no cap favors voters with more financial wealth, and thereby the lack of cap creates electoral inequity and imbalance among voters.

- 9. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 9 of 82 Chapter One: Electoral Finance This chapter focuses on Canadian electoral finance laws and the FDA's audit of them in terms of electoral fairness. Based on the political concepts of egalitarianism and political liberalism, the FDA team audits electoral finance laws according to their equity for registered candidates, parties, and voters (see Definition of Key Terms and Research Methodology for further explanation). The FDA team audits from the standpoint of a people's representative democracy. Table 1 below shows the FDA‘s audit variables, their corresponding audit weights, and results: Table 1 Electoral Finance Audit Scores and Percentages Electoral Finance Section Variables % Subsection Audit Weight Numerical Subsection Audit Weight Audit Results % Results Electoral Finance Transparency 20% 2.0 2.0 100% Contributions to Candidates & Parties 15% 1.5 1.25 83.3% Caps on Contributions to Candidates & Parties 20% 2.0 1.61 80.5% Campaign Expenditure Limits 22.5% 2.25 1.5 66.6% Caps on Third-party Expenditures 12.5% 1.25 0.005 0.4% Legislative Process 10% 1.0 1.0 100% Variables from Other Sections n/a n/a n/a n/a Total 100% 10 7.815 78.15% The FDA chose these subsections because they represent core areas of electoral finance. The audit of electoral finance includes examination of Canadian electoral finance legislation and the application of legislative research to the FDA matrices. Matrix scoring is based on an overall score of 0 to 10 out of 10. What follows are the audit questions, legislative research, and audit findings: Electoral Finance Transparency Audit Questions 1) Are candidate and party finances transparent to the public? 2) Are candidate and party finances transparent to candidates and parties only? 3) Are candidate and party finances transparent to the government only?

- 10. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 10 of 82 Legislative Research The Chief Electoral Officer shall publish the original election expenses return of registered parties and electoral campaign returns of candidates with one year of writ of election, and publish any updated versions of the returns as soon as practicably after he or she receives them (Elections Act, Article 412(1)). The Chief Electoral Officer shall publish the returns on financial transactions of registered parties and associations, and any updated versions (Elections Act, Article 412(2)(a)). The Chief Electoral Officer shall publish the leadership returns and contribution returns for leadership contestants, and any updated versions (Elections Act, Article 412(2)(b)). The Chief Electoral Officer shall publish the returns of nomination contestants, and any updated versions (Elections Act, Article 412(2)(c)). The Chief Electoral Officer shall publish a summary report or updated reports of candidates‘ election expenses (Elections Act, Article 412(3)). Within six months of becoming registered, a party will provide the Chief Electoral Officer with a statement of their current assets and liabilities, as of the day prior to their effective registration. The party must also provide a declaration by the chief agent of the party concerning the statement, and a report from the party's auditor containing the auditor's opinion of whether the information is based on standard accounting principles (Elections Act, Article 372). Registered political parties must submit to the Chief Electoral Officer an audited return of election expenses within six months after the Election Day (Elections Act, 429(3)). Registered political parties have to submit annual fiscal returns within six months of the end of the fiscal period (June 30) (Elections Act, 424(4)). The fiscal returns must contain all financial transactions for the registered party; the auditor‘s report on the financial transactions; and the chief agent‘s declaration of the financial transactions (Elections Act, 424(1)). Both of the above reports contain a variety of information; including, the total contributions received by the registered party and the number of contributors; the name and address of each contributor who contributed more than $200 and the date the registered party received the funds; and a statement of assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses (Elections Act, 424(2)(a)-(k)). The returning officers for electoral districts shall make available the financial disclosures of candidates to public upon request for six months during reasonable times for public inspection. Copies can be obtained for fee of 0.25 cents per page (Elections Act, 413(1), (2)). A returning officer shall retain financial disclosures for three years after the six month time period for public inspection (Elections Act, Article 413(3)). The Chief Electoral Officer shall publish a list of claims that are deemed to be contributions (Elections Act, Article 423(4)).

- 11. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 11 of 82 An unpaid claim mentioned in the financial transactions return referred to in subsection 424(1) or in an election expenses return referred to in subsection 429(1) that remains unpaid in whole or in part on the day that is 18 months after the end of the fiscal period to which the return relates or in which the polling day fell, as the case may be, is deemed to be a contribution to the registered party of the unpaid amount on the day on which the expense was incurred (Elections Act, Article 423.1 (1)). Candidates must submit to the Chief Electoral Officer an audited election expense report within four months of the polling day, or after a published notice of withdrawal or deemed withdrawal from the election (Elections Act, 451(4)). Electoral campaign returns need to include: a statement of election and campaign expenses; statements regarding disputed or unpaid claims; statement of contributions; the number of contributors; and the name and address if the contribution was more than $200 (Elections Act, 451(2)(a)-(k)). Candidates must also report all gifts or other advantages that exceed $500 individually or as a total from the same contributor to the Chief Electoral Officer except if given by a relative (Elections Act, 92.2(3)). This statement of gifts is due within four months of the polling day, or after a published notice of withdrawal or deemed withdrawal from the election (Elections Act, 92.2(5)). Audit Findings The financial transactions, records, and reports of candidates and parties are transparent to the public. Contributions to Candidates and Parties Audit Questions 1) Are contributions restricted to citizens? 2) Are contributions disallowed by foreigners, public institutions, and charities? 3) Are anonymous contributions set at a reasonable level? Legislative Research Only Canadian citizens or permanent residents may make contributions to registered candidates, parties, associations, and leadership and nomination contestants (Elections Act, Article 404(1)). Electoral campaign returns need to include: a statement of election and campaign expenses; statements regarding disputed or unpaid claims; statement of contributions; the number of contributors; and the name and address if the contribution was more than $200 (Elections Act, 451(2)(a)-(k)). Both of the above reports contain a variety of information; including, the total contributions received by the registered party and the number of contributors; the name and address of each contributor

- 12. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 12 of 82 who contributed more than $200 and the date the registered party received the funds; and a statement of assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses (Elections Act, 424(2)(a)-(k)). Canadian citizens and permanent residents cannot make cash contributions that exceed $20.00 (Elections Act, Article 405.31). Any person who is not a Canadian citizen or permanent resident is disallowed from inducing electors to vote or refrain from voting or vote or refrain from voting for a particular candidate (Elections Act, Article 331). Audit Findings The FDA auditors awarded near full marks for the above three subsections because contributions are restricted to citizens whereas foreigners, public institutions and corporations are not allowed to contribute. They subtracted points, however, because the maximum anonymous contribution limit is $200.00, which is more than double the FDA standard of maximum anonymous contribution of $100.00 (determined by mean national income and benchmarks of Canadian provinces and foreign countries). The FDA assumes that a relatively low amount for anonymous contributions helps to prevent electoral finance wrongdoing. Caps on Contributions to Candidates and Parties Audit Questions 1) Are the caps on candidates' and parties' contributions reflective of per capita net income level? 2) Are the caps on candidates own contributions reflective of per capita net income level? Legislative Research The 2010 Canadian disposable per capita income is $26,572 (Economic Statistics Report, 2012). Individuals are disallowed from making contributions in excess of $1,000 in total for any calendar year to a registered party (Elections Act, Article 405 (1)(a)). Individuals are disallowed from making contributions in excess of $1,000 in total for any calendar year to registered associations, nomination contestants and candidates of a particular registered party (Elections Act, Article 405 (1)(a.1)). Individuals are disallowed from making contributions in excess of $1,000 in total for a particular election to candidates who are not member of a registered party (Elections Act, Article 405 (1)(b)). Individuals are disallowed from making contributions in excess of $1,000 in total to the leadership contestants of a particular leadership contest (Elections Act, Article 405 (1)(c)).

- 13. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 13 of 82 Contributions to candidates seeking the endorsement of a particular registered party or contributions to candidates not endorsed by a particular party shall be deemed contributions (Elections Act, 405 (3)). Contributions to own campaign that do not exceed $1,000 in total by a nomination candidate or candidate of registered party shall not deemed a contribution (Elections Act, 405 (4)). Contributions to own campaign that do not exceed $1,000 in total by an independent candidate shall not deemed a contribution (Elections Act, 405 (4)). Contributions to own campaign that do not exceed $1,000 in total by a candidate of registered party for leadership contest shall not deemed a contribution (Elections Act, 405 (4)). The total individual contributions allowed in an election year are around $4,000 and total candidate contributions are around $5,000 to $6,000 (Elections Act, Article 405). Contribution caps are subject to adjustment for inflation based on the Consumer Price Index, calculated on the basis of 1992 being equal to 100 and denominator of 119, which is the average annual Consumer Price Index. Adjustments are rounded off to the nearest one hundred dollars (Elections Act, 405.1 (1)). Audit Findings The FDA awarded points for caps on candidate and party contributions during the campaign period. Through consensus and Desjardins‘ household budget calculator, the FDA determined that 10 percent of per capita net income is a reasonable maximum contribution amount (Determine How Much to Allocate to Each Expense, 2013). The 10 percent contribution amount takes into consideration other expenditures such as housing, food, services like hydro and heat, clothing, and health. The caps for candidate and party contributions ($4,000 over four years) are set significantly lower than the 10 percent of the Canadian per capita net income threshold ($10,608 over four years). The limit on contributions by candidates to their own campaigns in an election year ($5,500) is in excess of the FDA‘s maximum cap of $2,652 (in a year). The score of 1.25 and 0.36 reflect this assessment. Campaign Expenditure Limits Audit Questions 1) If there are campaign expenditure limits on candidates and parties, are they set high enough and still reasonably attainable by all registered candidates and parties? 2) If there are public subsidies or other financial instruments, do they create an equal level of campaign finances for candidates and parties? Legislative Research The 2010 Canadian disposable per capita income is $26,572 (Economic Statistics Report, 2012).

- 14. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 14 of 82 Candidate electoral expense limits are based on the amount calculated for an electoral district and subject to inflation adjustment (Elections Act, Article 440). Elections Canada determines electoral expenditure limits for electoral districts based on: 1) the preliminary lists of electors in a district: a) $2.07 for each of the first 15,000 electors, b) $1.04 for each of the next 10,000 electors; and c) $0.52 for each of the remaining electors (Elections Act, Articles 441(1)(a), 441(3)). If the number of electors on the preliminary list of electors is less than the average number of electors on all preliminary lists of electors in a general election, then in making the calculation above, the number of electors is deemed to be half-way between the number on the preliminary list and the average number (Elections Act, 441(4)). If a candidate whose nomination is endorsed by a registered party dies at the period beginning 2:00 p.m. on the 5th day of the closing day for nominations and ending on polling day, then the base electoral expenditure amount for the district is increased by 50 percent (Elections Act, 441(2)). If the number of electors per square kilometer is less than 10 electors, then the amount calculated above is increased by the lesser of $0.31 per square kilometer and 25 percent of that amount (Elections Act, Article 441(6)). 1) the revised lists of electors in a district: a) $2.07 for each of the first 15,000 electors; b) $1.04 for each of the next 10,000 electors; and c) $0.52 for each of the remaining electors (Elections Act, Article 441(7)). If the number of electors on the revised list of electors is less than the average number of electors on all revised lists of electors in a general election, then in making the calculation above, the number of electors is deemed to be half-way between the number on the revised list and the average number (Elections Act, 441(8)). If the number of electors per square kilometer is less than 10 electors on the revised list of electors, then the amount calculated above is increased by the lesser of $0.31 per square kilometer and 25 percent of that amount (Elections Act, Article 441(10)). Candidates cannot exceed the electoral expenditure limits for their electoral district, and candidates or official agents of candidates or other authorized persons cannot collude in order to circumvent electoral expenditure limits (Elections Act, Articles 443(1), 443(2)). The Chief Electoral Officer determines for each quarter an allowance payable to a registered party whose candidates received either 2 percent of the popular vote or 5 percent of the valid votes cast in the electoral districts of the candidates endorsed by the party in for the most recent general election (Elections Act, 435.01(1)(a)-(b)).

- 15. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 15 of 82 The quarterly allowance is the multiplication of the valid votes cast in the most recent general election by $0.3825 for 2012; $0.255 for 2013; and $0.1275 for 2014. All quarters begin on April 1st (Elections Act, 435.01(2)(a)-(c)). The Conservative government revised the federal budget to phase out the public subsidies for federal political parties beginning April 1st 2012 (Smith, J, July 4, 2012). The annual subsidy was lowered from $2.04 in 2011 to $1.53 per vote in 2012 and will be further reduced each year on April 1st until it is eliminated in 2015 (Smith, J, July 4 2012). If a registered party receives 2 percent of the votes cast in the election or 5 percent of the number votes cast in the electoral district in which the part endorsed a candidate, then 50 percent of the parties‘ electoral expenses are refunded (Elections Canada, Article 435 (1)). Audit Findings In each Canadian electoral district, there is an average of 78,758 voters with income. Candidates need 0.881 cents from each elector to attain the maximum legal expenditure limit. The average maximum expenditure limit amounts to $69,385.80. According to FDA consensus and Desjardins‘ household budget calculator, $2,652 is the maximum available from each elector making the total available at $208,866,216. On average there are approximately eight candidates per riding, ergo, there is $555,232 funds needed. According to these calculations, there are potential excess funds of $208,310,984, and therefore the expenditure limit is reasonably attainable in terms of funds by all registered candidates and parties. Whether or not voters want to contribute to all registered candidates and parties is a separate issue. Using their professional judgment and considering for example campaign advertising expenses and venue expenses, FDA auditors determine that $69,385.80 is a reasonable amount of electoral funds to campaign in a district of 78,758 voters, and with no candidate above $69,385.80 expenditure limit. Public subsidies are only available for parties with at least one seat in parliament, and therefore create more financial inequality rather than equality between all registered parties. Caps on Third-party Spending Audit Questions 1) If there is third-party spending, is it restricted to citizens only? 2) If there are caps on third-party spending, are they high enough and reasonably attainable by all adult citizens? 3) Are there public subsidies, or other financial instruments, that create an equitable level of third- party spending?

- 16. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 16 of 82 Legislative Research The total expenses limit for election advertising for third parties is $197,100 and the expenses limit per electoral district is $3,942 for the period from April 1 2012 to March 31 2013 (Limit on Election Advertising Incurred by Third Parties, 2012). Such limits include advertising to either ―promote or oppose the election‖ (Election Advertising Expenses, 2012; Elections Act, Articles 350, 414). In order for a third party to determine to which limit it is subject ($3,942 or $197,100) it needs to consider its particular situation. For instance, if an average person remarks that certain advertising refers ―one or more specific candidates in a given riding,‖ the limit would be $3,942 (Questions and Answers about Third Party Advertising, 2010). On the other hand, if a third party is involved in an advertising campaign relevant to a registered political party, and if an average person recognizes such ―advertising is aimed at a national, regional or provincial audience,‖ the limit is $197,100 (Questions and Answers about Third Party Advertising, 2010). Assuming that the advertising campaign aims at promoting or opposing several candidates in multiple ridings, the limit of $3,942 is multiplied by the amount of ridings until it reaches the limit of $197,100 (Elections Act, Articles 319, 350, 414). Also noteworthy is that for third party spending of $5,000 or over, an external auditor must be appointed (Questions and Answers about Third Party Advertising, 2010). Foreign donations are not satisfactory, including from individuals who are not citizens or permanent residents, foreign organizations not conducting business activities in Canada, trade unions without bargaining rights in Canada, or foreign political parties and governments (Elections Act, Article 358). The FDA researchers found no public subsidies or other financial instruments for third-party expenditures. Audit Findings Corporations, labor unions, and citizens can contribute to campaign election campaigns, parties, and candidates. The limit is set at $197,100, which, according to FDA consensus, is about 74 times more than the 10 percent of per capita net income ($2,652 over one year) available for citizen personal expenditure. The FDA acknowledges that $197,100 is a reasonable and likely cost for a national advertising campaign; however, third-party spending for this can affect public opinion in a non- democratic way. The FDA believes that contributions to candidates, parties, and party associations should fund these advertising campaigns, which would then create the basis to eliminate third-party expenditures. Finally, electoral law does not mandate public subsidies for third-party expenditures. Legislative Process Audit Question 1) Is there an effective legislative process to enforce electoral finance laws?

- 17. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 17 of 82 Legislative Research The Chief Electoral Officer (CEO), appointed by the House of Commons, is responsible for the supervision, direction, and conduct of the federal election. The CEO must enforce the provisions of and ensure compliance with the Elections Act and other legislation pertaining to the election (Elections Act, Article 13(1) (2); Article 16). During the election period and for thirty days following polling day, the CEO may adapt these provisions in order to manage electoral emergencies (Elections Act, Article 17). The CEO can educate the public about federal elections, the democratic process, and electoral rights and regulations using any media forum or communication s/he considers appropriate (Elections Act, Article 18(1) (2)). The Elections Act outlines various prohibitions that are subject to penalty. For example, one cannot disclose information about an electors vote, interfere with an elector while voting, make false statements while applying for registration as a candidate, party, or voter, or prevent or persuade an elector from voting through intimidation or duress (Elections Act, Article 281-282). The Commissioner of Canada Elections, appointed by the CEO, ensures compliance and enforcement of the Act. If the CEO believes an offense has occurred, s/he directs the Commissioner to proceed with an inquiry. If after this inquiry the Commissioner believes that an offense has occurred, s/he refers the matter to the Director of Public Prosecutions, who then decides to initiate a prosecution. The CEO informs both the Commissioner and the Director throughout the process. The offense can be prosecuted no later than 5 years after the Commissioner was made aware of the matter and no longer than 10 years of when it occurred (Elections Act, Articles 509-511, 512, 514). Other obstructions of the election process that demand penalty include: disrupting or inciting disorder at public meetings intended for election purposes, offering or accepting a bribe in order to influence a vote, unauthorized use of personal information in the elector register, an employer not allowing reasonable time for employees to vote, and unauthorized ballot printing (Elections Act, Article 480-482; Elections Act, Table of Offences, 2000). Contraventions of the Act are subject to strict liability offences. Summary convictions range from a fine of not more than $1,000 or imprisonment for no longer than three months or both, $2,000 or six months imprisonment or both, to $5,000 and a year imprisonment or both, depending on intent. For registered parties and third parties, fines can reach $25,000 and imprisonment of five years or both (Elections Act, Article 500). Upon conviction, and depending on the nature and intent of the offense, additional penalties might include community service, financial compensation to those who suffered damages because of a financial contravention, party deregistration and asset liquidation, or whatever reasonable measure the court finds appropriate (Elections Act, Article 501(1) (2)). The Act differentiates illegal or corrupt practices from general contraventions of electoral law. These apply in particular to candidates and agents of candidates who breach provisions including, but not limited to, publishing false statements regarding the inclusion or withdrawal of another candidate;

- 18. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 18 of 82 foreign broadcasting; exceeding limits on election expenses; and purposefully obstructing the democratic process (Elections Act, Article 502; Elections Act, Table of Offences, 2000). Some offenses, including but not limited to, offering or accepting a bribe to influence an elector; intentionally preventing public meetings related to election; intimidation or duress of an elector; knowingly voting more than once or without being qualified; obstruction of election officer; or if an election officer does not return election documents and materials, are subject to a $5,000 fine, a five year imprisonment, or both (Elections Act, Table of Offences, 2000). Third parties that contravene the Act are liable on conviction of fines ranging from $10,000 to $25,000 (Elections Act, Article 505). If a candidate or party agent knowingly makes or publishes false statements about a candidate; accepts unauthorized contributions; fails to provide complete and accurate financial statements to the CEO within the required period; exceeds contribution limits; or forges a ballot in any way with the intention of influencing the elector, the penalty is a $5,000 fine, five year imprisonment, or both. In addition, the CEO can de-register a party and liquidate its assets (Elections Act, Table of Offences, 2000). The penalty for exceeding election advertising expense limits is $1,000, three months imprisonment or both; however, the penalty for liable third parties is a fine of up to five times the amount spent over the limit. The penalty for the chief agent that fails to identify the party and candidate in advertisements, uses foreign contributions, willfully exceeds the election expense limit, submits incomplete, false, or late documents, or does not claim all contributions etc. is a $1,000 fine, three month imprisonment, or both. The registered party conducting these infractions is liable for a $25,000 fine (Elections Act, Table of Offences, 2000). Audit Findings The FDA auditors use professional judgment on the score regarding reasonable legislative processes to enforce electoral finance laws. The FDA auditors identified a comprehensive and effective legislative process to enforce electoral finance laws, including fines reflective of the severity of the offense, prison terms of up to five years, and detailed investigation, trial, and appeal processes. Total score for the electoral fairness on electoral finance: 78.15 percent out of 100 percent.

- 19. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 19 of 82 Electoral Finance Analysis The FDA measured a very satisfactory score of 78.15 percent for Canadian federal electoral finance legislation. Auditors identified a strong process for financial transparency, enforcement, and limitations on contributions to candidates and parties by citizens. However, the inequality of public subsidies to registered parties, caps on third-party expenditure that are grossly inconsistent with per capita net income, and the inclusion of corporations and trade unions in third-party expenditure partly offset these positive aspects. The following is a summary of the FDA‘s key findings regarding the Canadian federal electoral finance laws and their corresponding impact on a free and democratic society: 1) Public subsidies are only available to registered political parties whose candidates received either 2 percent of the popular vote or 5 percent of the valid votes cast in the electoral districts of the candidates endorsed by the parties. Impact In Canada, public subsidies are available to parties that garnered a certain percentage of the popular vote in the current election. Due to the level of popular vote required, this practice generates financial inequality with new and smaller registered parties. It also produces inequality between parties in the Parliament because the amount of the subsidy is linked to the amount of popular vote received. In other words, subsidies favour certain large and established parties, reducing electoral competition and weakening Canadian democracy. The subsidy is scheduled to be phased out in 2015. In addition, a public subsidy in form of a 50 percent refund of a party‘s campaign expenditures is available if the party attains either 2 percent of the popular vote or 5 percent of the valid votes cast in the electoral districts of the candidates endorsed by the party. Again, this public subsidy favours certain large and established parties over other large, established parties (which have lower expenditures) and new and small parties. 2) The cap on third-party expenditure is set at $197,100, about 18.6 percent more than Canada‘s per capita net income of $26,572. Through consensus and based on Desjardins‘ household budget calculator, the FDA determine that 10 percent of per capita net income or $10,608 (over four years) is a reasonable maximum contribution amount (Determine How Much to Allocate to Each Expense, 2013). Therefore, most Canadians could not afford spending more than 5.38 percent of the cap. Impact The excessively high cap placed on third-party spending favours wealthy, minority interests. The majority of Canadians cannot afford this spending limit, which allows the minority to have a disproportionate and undue influence on an election and democratic discourse. The FDA acknowledges that $197,100 is a reasonable and likely cost for national advertising campaigns; however, third-party spending for this can affect public opinion in a non-democratic way. Therefore, the FDA believes that electoral law should not allow third-party expenditures,

- 20. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 20 of 82 and instead contributions to candidates, parties, and party associations should fund national and district advertising campaigns. 3) Corporations and trade unions can participate in third-party expenditures. Impact Corporations and trade unions can contribute to campaign election campaigns, parties, and candidates. However, the excessive cap on third-party expenditures allows these organizations greater opportunity to influence an election than the majority of the electorate is able to do. This influence interferes with the voice of the people as manifest in election discourse, and thereby weakens Canadian democracy.

- 21. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 21 of 82 Chapter Two: Media Election Coverage This chapter focuses on Canada‘s media laws and the FDA's audit of them. Based on the concepts of egalitarianism and political liberalism, the FDA audit team examined media laws according to the standard of impartial and balanced political coverage before, during and after a campaign period (see Definition of Key Terms and Research Methodology for further explanation). Table 2 below shows the FDA‘s audit variables, their corresponding audit weights, and results: Table 2 Media Election Coverage Audit Scores and Percentages Media Election Coverage Section Variables % Subsection Audit Weight Numerical Subsection Audit Weight Audit Results % Results Broad and Balanced Media Election Coverage 30% 3.0 0.0 0.0% Media Ownership 15% 1.5 0.235 15.6% Survey/Polls 5% 0.5 0.5 100% Freedom of Media 40% 4.0 4.0 100% Press Code of Practice/Conduct 10% 1.0 0.0 0.0% Variables from Other Sections n/a n/a n/a n/a Total 100% 10 4.735 47.35% Broad and Balanced Media Election Coverage Audit Questions 1) During the campaign period, is the media (private and public) required legally to publish/broadcast broad/balanced coverage of registered candidates and parties? 2) Outside of the campaign period, is the media legally required to publish/broadcast pluralistic/balanced coverage of registered parties? 3) If the media is legally required to publish/disseminate broad and balanced political coverage, are there reasonable monitoring and penalty mechanisms in place? Legislative Research During an election period, electoral law mandates that licensed broadcasters must allocate time for ―the broadcasting of programs, advertisements or announcements of a partisan political character on an equitable basis to all accredited political parties and rival candidates represented in the election or referendum‖ (Television Broadcasting Regulations, 1987). The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) Act presents the regulations regarding political advertising and broadcasting during an election period. Broadcasters are required to cover Canadian elections and must give all candidates, parties and issues ―equitable‖

- 22. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 22 of 82 coverage during the campaign period. Equitable does not imply equal, broadcasters must simply take ―reasonable‖ steps to present the views and positions of all parties (Public Notice CRTC, 1988). During the election period, broadcasters are responsible for informing the public about the central issues regarding the election, and should present the positions and platforms of candidates and parties relating to those issues (Public Notice CRTC, 1988). These guidelines pertain to television broadcasters, radio stations, and specialty television services licensed by the CRTC. They do not apply to pay television services or internet communications; therefore, they are not obliged to provide time to political parties, but may do so (Broadcasting Guidelines, 2011). Broadcasters are not required to include all parties or candidates in debate programs during the election campaign (Public Notice CRTC, 1988). Licensed broadcasters cannot broadcast from outside of Canada during an election period in any matter regarding the election or in an effort to influence the vote (Elections Act, Article 330(1) (2)). The penalty for broadcasters and network operators that breach the Act during an election period is a $25,000 fine. Offences include but are not limited to: failure to provide the information, results or sponsor of a survey; willfully transmitting election results during the blackout period or prematurely; purposefully failing to make broadcasting time available to authorized parties and candidates; willfully charging more than the lowest rate for broadcasting time or advertising space; willfully failing to comply with the allocation of minutes; making additional time available to one party but not equivalent time to other eligible parties (Elections Act, Table of Offences, 2000). Audit Findings The FDA auditors found no legislation requiring the media to provide broad and balanced election coverage during the 36-day campaign period or outside of this period. Candidate and party advertisement is a separate issue examined in the Candidate and Party section. Media Ownership Concentration Laws Audit Questions 1) If there are media concentration laws, are they effective in causing a plurality of political discourse? 2) If there is no legal requirement of media plurality, impartiality, and balanced content or media ownership concentration laws, are there any other laws that are effective in causing a plurality of political discourse before and during an election period? Legislative Research Canada has a federal competition bureau which is part of Industry Canada. The Competition Bureau maintains and encourages fair competition in the Canadian marketplace (Competition Bureau, 2013).

- 23. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 23 of 82 The Canadian Competition Act provides general regulation on uncompetitive practices in the Canadian marketplace such as price fixing, product collusion with competitors, and market collusion with competitors. The Competition Act does not disallow oligopolies or monopolies (Competition Act, 2010). During an election period, electoral law mandates that licensed broadcasters must allocate time for ―the broadcasting of programs, advertisements or announcements of a partisan political character on an equitable basis to all accredited political parties and rival candidates represented in the election or referendum‖ (Television Broadcasting Regulations, 1987). The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) Act presents the regulations regarding political advertising and broadcasting during an election period. Broadcasters are required to cover Canadian elections and must give all candidates, parties and issues ―equitable‖ coverage during the campaign period. Equitable does not imply equal, broadcasters must simply take ―reasonable‖ steps to present the views and positions of all parties (Public Notice CRTC, 1988). During the election period, broadcasters are responsible for informing the public about the central issues regarding the election, and should present the positions and platforms of candidates and parties relating to those issues (Public Notice CRTC, 1988). These guidelines pertain to television broadcasters, radio stations, and specialty television services licensed by the CRTC. They do not apply to pay television services or internet communications; therefore, they are not obliged to provide time to political parties, but may do so (Broadcasting Guidelines, 2011). Broadcasters are not required to include all parties or candidates in debate programs during the election campaign (Public Notice CRTC, 1988). Audit Findings The FDA auditors found no legislation limiting media ownership concentration in Canada. Canadian Antitrust Laws, which aim to provide a remedy against uncompetitive marketplace practices, have no impact on media ownership concentration unless it derives from anti-competitive conduct. Auditors found that four out of the seventeen registered parties were favoured in media coverage during the 2011 Canadian Federal General Election. Although there are "equitable" requirements for media coverage, networks offer parties the option to purchase up to 6.5 hours of broadcast time at regular market price, which not all parties can afford. There are minor penalties (up to $25,000 fine) for offences that explicitly work to restrict media time to specific parties. In addition, media invited the leaders of only four of the national parties to participate in the two national debates. The score of 0.235 reflects the media bias of the four parties (4 out 17 equals 23.5 percent).

- 24. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 24 of 82 Surveys/Polls Audit Question 1) Are there reasonable public disclosure requirements on surveys and polls in terms of their methodology, data, and funder? Legislative Research The first individual to broadcast a survey, as well as any publishing within 24 hours after the initial publication, must provide the survey's sponsor, conductor, date conducted, sample population and number of participants. A margin of error and indication of the use of non-recognized statistical methods must also be indicated when applicable. If the survey is transmitted by a means other than broadcasting, survey wording and information about obtaining a more detailed report regarding the survey must also be provided. A maximum fee of $0.25 may be charged for this report (Elections Act, Articles 326, 327). No person may publish a non-previously released survey prior to the closing of polls on polling day in a given district (Elections Act, Article 328). Audit Findings The FDA auditors found comprehensive legislation on public disclosure of the survey and poll information including funding sources and methodology. Freedom of the Media Audit Question 1) Does constitutional or legislative law establish freedom of the media (including journalists)? Legislative Research The media can only shoot general footage from the door of polling stations, and must not hinder voters or compromise the secrecy of the vote. This limited access is only allowed if the location is suitable for media set-up (Elections Canada, July 19, 2012). 1) Constitutional The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms provides that everyone has the fundamental freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression; including, freedom of the press and other media of communication (Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Section 2(b)). 2) Legislative Broadcast Act

- 25. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 25 of 82 The Broadcast Act, although Legislative, should be interpreted and applied in a manner consistent with the fundamental freedom of expression. Any broadcasting undertakings will enjoy journalistic, creative, and programming independence (Broadcast Act, Article 2(3)). The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (the Commission) may regulate the proportion of time devoted to the broadcasting of programs; including, advertisements or announcements, of a partisan political character. The Commission will assign the time on an equitable basis to the political parties and candidates (Broadcast Act, Article 10(1)(e)). Elections Act The Commission, at most four days after the announcement of a general election, will prepare and send guidelines describing the applicability of the Broadcast Act to the conduct of all licensed broadcasters and network operators (Elections Act, Article 347). The Elections Act provides a blackout period for election advertising to the public. The blackout begins on polling day and lasts until the close of all the polling stations in the electoral district (Elections Act, Article 323(1)). Audit Findings The FDA auditors found nothing in The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms or other election legislation that would unreasonably limit the freedom of the press. Press Code of Practice/Conduct Audit Questions 1) Does a Code of Practice/Conduct that supports impartial, balanced electoral coverage guide the press? 2) If a Code of Practice/Conduct that supports impartial, balanced electoral coverage guides the press, is the Code of Practice/Conduct enforceable? Legislative Research CEP Media has a code of ethics but does not provide electoral coverage guidelines (Code of Ethics, 2011). The Canadian Journalism Project has ethics for photojournalism but does not provide electoral coverage guidelines (Burkholder, 2010). The Canadian Association of Journalists does not have specific, electoral coverage guidelines but their principles for ethical journalism include reporting on a wide variety of viewpoints and values, reporters do not endorse political candidates or causes, they report the truth to serve democracy,

- 26. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 26 of 82 inform the public of institutions and people who are elected, freely comment on the activities of publicly elected bodies, are careful about getting politically involved in activities, their journalists must declare any real or potential conflicts of interest if they choose to become engaged in outside political activities, and they avoid biases that would affect their reporting (Principles of Ethical Journalism, 2010). The Globe and Mail has a Privacy Policy but it does not include a code of conduct during an election period (Globe Privacy Code, 2012). The Globe and Mail has an Accessibility Policy but it does not include a code of practice during an election period (Accessibility Policy, 2012). Postmedia Network Canada Corp. has a Code of Business Practice for its subsidiaries (which includes the National Post) but the code does not include guidelines for election coverage. Although Postmedia personal are permitted to participate in political activities as private citizens, they may not do so during their working hours, use Postmedia facilities, or use company funds (Code of Business Conduct and Ethics, 2011). Audit Findings The FDA auditors did not find legislation to mandate broad and balanced election coverage via a Code of Practice/Conduct for the media. Although many private press organizations and newspapers follow a Code of Practice and/or guidelines for conduct, none of these guidelines includes requirements for broad and balanced election coverage. Total score for the electoral fairness on media election coverage: 47.35 percent out of 100 percent.

- 27. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 27 of 82 Media Election Coverage Analysis FDA auditors measured a failing score of 47.35 percent for Canadian federal legislation relating to media election coverage in the media during and in between the 36-day campaign period. Media election coverage received the lowest score of the four audit sections and is the only section to receive a failing score. There are minimal limitations or checks on freedom of expression in the Canadian media sector. As a result, this sector operates in a Darwinian-like fashion in where the most powerful media corporations have the most influence over public discourse in general and in particular to the FDA examination, over electoral discourse and outcomes. This practice may generate narrow and imbalanced election coverage and can allow certain minority interests to influence the democratic process. The following is a summary of the FDA‘s key findings regarding the Canadian federal media laws and their corresponding impact on a free and democratic society: 1) There is no legislated media requirement for broad and balanced political coverage both during and outside of the campaign period. Impact Political coverage of candidates and parties both during and outside of an election can be narrow and imbalanced. This system favours certain established, large, or incumbent parties over smaller or new candidates and parties, and as a result, the public lacks information regarding their complete electoral choices. 2) There are no media ownership concentration laws. Impact With no media ownership concentration laws and no requirement for broad and balanced election coverage, there is the potential for oligopolistic and monopolistic media ownership, and thereby narrow and imbalanced election coverage. 3) The Canadian press has no legislated or private code of conduct/practice for broad and balanced coverage during elections. Impact Political coverage of candidates and parties both during and outside of an election can be narrow and imbalanced. This system favours certain established, large, or incumbent parties over smaller or new candidates and parties, and as a result, the public lacks information regarding their complete electoral choices.

- 28. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 28 of 82 Chapter Three: Candidates and Parties This chapter focuses on Canadian laws pertaining to candidates and parties. The FDA audit team examines election laws according to their equity for registered candidates and parties (see Definition of Key Terms and Research Methodology for further explanation). Table 3 below shows the FDA‘s audit variables, their corresponding audit weights, and results: Table 3 Candidates and Parties Audit Scores and Percentages Candidates & Parties Section Variables % Subsection Audit Weight Numerical Subsection Audit Weight Audit Results % Results Campaign Period 2% 0.2 0.12 60% Methodology for Election Winners 2% 0.2 0.0 0.0% Electoral Boundaries 2% 0.2 0.2 100% Process of Government 10% 1.0 0.0 0.0% Registration of Candidates 2% 0.2 0.2 100% Freedom of Expression and Assembly 20% 2.0 2.0 100% Registration of Parties 2% 0.2 0.2 100% Electoral Complaints 3% 0.3 0.3 100% Presentation of Ballots 1% 0.1 0.1 100% Scrutineers 1% 0.1 0.1 100% Candidate and Party Campaign Advertisement 6% 0.6 0.0 0.0% Variables from Other Sections 49% 4.9 2.67 54.48% Total 100% 10 5.89 58.93% Campaign Period Audit Question 1) Does the length of the campaign period reasonably and fairly allow all registered candidates and parties enough time to share their backgrounds and policies with the voting public? Legislative Research An election must be held a minimum of 36 days after a proclamation by the Governor in Council for a general election to be held. Parliament must sit at least once every 12 months (Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Article 5; Elections Act, Article 57).

- 29. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 29 of 82 Audit Findings Using professional judgment and through consensus, FDA auditors determine that 60 days is adequate time for candidates and parties, including new candidates and parties, to share their backgrounds and policies with the voting public. The FDA believes that the length of a campaign period should take into account public interest and attention span, the financial resources of candidates and parties, and allow sufficient time for new and small parties to inform the public of their political platforms. Therefore, the FDA auditors deducted 43.33 percent (or 0.08) from the maximum score of 0.2. Methodology for Determining Winners of Districts Audit Questions 1) Is the determination of election winners based on first-past-the-post? 2) Is the determination of election winners based on proportional representation closed list? 3) Is the determination of election winners based on proportional representation open list? Legislative Research According to the Canada‘s Elections Act, the electoral system in Canada is referred as ―single member plurality‖ also known as ―first-past-the-post‖ framework. The aforementioned means that the candidate with the most votes in a given electoral district (geographically the Canadian territory is divided in electoral districts, also known as ridings) will be elected as a member of the Parliament (MP). There is no need to have a 50 percent of the vote to access to the House of Commons, namely, a candidate that has one more vote than his main opponent wins (The Electoral System of Canada, 2012). Noteworthy, that in accordance to the principle ―first-past-the post‖ there is not a proportional system in Canada. The fact that a proportional system does not exist in the Canadian electoral system implies that representation either by close or open list does not apply in this electoral system. According to Lijphart´s Patterns of Democracy, proportional systems exist in political systems that have a wide variety of ethnic/religion/race/language differentiations (Lijphart, 1999). This could apply to Canada, however, due to the numerous political parties that contend in the electoral system in Canada (In the 2006 General Election, there were 15 parties participating, and in 2011 General Election, there were 17 parties (The Electoral System of Canada, 2012). Proportional representation causes diffusion. The rationale goes, if you want that minorities get represented in the chamber, a shorter amount of parties would be a prerequisite in order to suffice the necessities of those groups, since, with that wide variety the proportional representation would imply that each party may have one or two representatives in the House of Commons which in the end is useless for purposes of representation. However, under proportional systems, most of the federal Canadian parties due to low total votes received would not factor in these systems. Presently, there are only 5 federal parties that would be impacted by proportional systems (Canadian Federal Election, 2011).

- 30. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 30 of 82 Audit Findings In Canada, a first-past-the-post voting system decides election winners. The first-the-past-post system does not give other parties an opportunity at the next seat nor does it base seats on proportion of votes cast. Table 4 First-Past-The-Post Examples Candidates for Riding A Total Votes Seat Winner Candidate A 65,000 Candidate A Candidate B 64,500 Candidate C 15,000 Candidates for Riding B Total Votes Seat Winner Candidate D 45,000 Candidate D Candidate E 44,780 Candidate F 40,456 The FDA believes that proportional representation is a more effective system to capture the will of the majority. In proportional representation, candidates win seats based on the proportion to the number of votes cast for them and a formula of vote reduction for each time a party wins a seat, which then allows other parties increased opportunity at winning the next seat. For example, the Sainte-Laguë method, which is used on New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and Germany, adheres to this calculation: the first round of seat allocation for all parties no reduction; all other seat allocations have the following deduction (Sainte-Laguë method, 2013): Total number of votes received . 2 x (number of seats allocated) + 1 Table 5 Proportional Representation (Sainte-Laguë Method) Example Parties Total Votes Seat 1 Seat 2 Seat 3 Seat 4 Party A 50,000 Party A (wins) (50,000) Party B (wins) (30,000) Party C (wins) (20,000) Party A (wins) (16,666) Party B 30,000 Party B (30,000) Party C (20,000) Party A (16,666) Party B (10,000) Party C 20,000 Party C (20,000) Party A (16,666) Party B (10,000) Party C (6,666) Party D 5,0000 Party D (5,000) Party D (5,000) Party D (5,0000) Party D (5,000) Consequently, first-past-the-post is only reflective of the candidate with the most votes in each district; whereas, proportional representation is reflective of the most of the votes cast in each district. Therefore, the political representatives under proportional representation are more reflective of the voice of the electorate than under first-past-the-post.

- 31. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 31 of 82 Electoral Boundaries Audit Question 1) Is the process for determining electoral boundaries reasonable and fair for all registered candidates and parties? Legislative Research 1) Constitution of Canada The Constitution of Canada requires that the number of seats in the House of Commons be recalculated and the boundaries of federal electoral districts be reviewed after each 10 year census (Constitution Act, Section 51(1), 1867). The population of each province is divided by the electoral quotient (111,166) to obtain the number of members for each province (Constitution Act, Section 51(1), Rules 1, 6(a), 1867). NOTE: The electoral quotient is adjustable to reflect average provincial population growth since the previous redistribution. The senatorial clause guarantees that no province has fewer seats in the House of Commons than it has in the Senate (Constitution Act, Section 51A, 1867). The grandfather clause guarantees each province no fewer seats than it had in 1985 (Constitution Act, Section 51(1), Rule 2, 1867). The representation rule only applies to a province whose population was overrepresented in the House of Commons during the last redistribution process. If the province would now be under- represented, it will be given extra seats so that its share of House of Commons seats is proportional to its share of the population (Constitution Act, Section 51(1), Rules 3-4, 1867). Three seats are allocated to the territories – one for each of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut (Constitution Act, Section 51(2), 1867). SUMMARY: Provincial population ÷ Electoral quotient (111,166) = Initial provincial seat allocation Application of the "senatorial clause" and "grandfather clause" Application of the "representation rule" Total provincial seats + One seat per territory = Total number of seats 2) The redistribution of federal electoral districts: The Chief Statistician prepares an estimate of each province‘s population using census data and sends the information to the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 12.1, 1985).

- 32. Foundation for Democratic Advancement | 2013 Electoral Fairness Audit of Canada May 27, 2013 Page 32 of 82 The CEO uses the population estimates to calculate the number of House of Commons members assigned to each province. The calculation is based on the formula found in the Constitution. The findings are published in the Canada Gazette (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 14(1)). After publication of the findings, each province prepares a report recommending reasons and concerns for its division into electoral districts; the description of the boundaries; the representation; and the name of the district (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 14(2)). The Chief Statistician prepares and sends to the CEO after each 10 year census a return showing the population of: Canada, each province, each electoral district, and by enumeration areas (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 13(1)). The CEO sends the population information to each province‘s Commission a long with a map showing the population distribution (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 13(2)(a)- (b)). The Governor in Council establishes a three-member commission for each province within 60 days after the publication of each 10 year census. The Commissions are published in the Canada Gazette (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 3(1)(a)). NOTE: Commissions are not required for Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and Yukon because each is a single electoral district. Each three-member Commission consists of a chairperson and two other appointed members (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 4). The chairperson is appointed by the Chief Justice of the province from among the judges the Chief Justice presides over (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 5(1)). The Speaker of the House of Commons appoints the remaining two members of the Commission. The appointees must reside in the province (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 6(1)). The members of the Commission cannot be members of the Senate, the House of Commons, a legislative assembly, or legislative council (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 10). Each Commission prepares a map or drawing showing the suggested division of the province into electoral districts; the population of the district; and the name. The Commission must provide at least one opportunity for the public‘s involvement in the drawing of the map. Notice to the public is published in the Canada Gazette and one newspaper of general circulation at least 30 days before the hearing indicating the time and place (Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, Article 19(1)-(3)). Each Commission considers the following before creating an electoral district: the community of interest; community identity; historical pattern of electoral districts; and a manageable